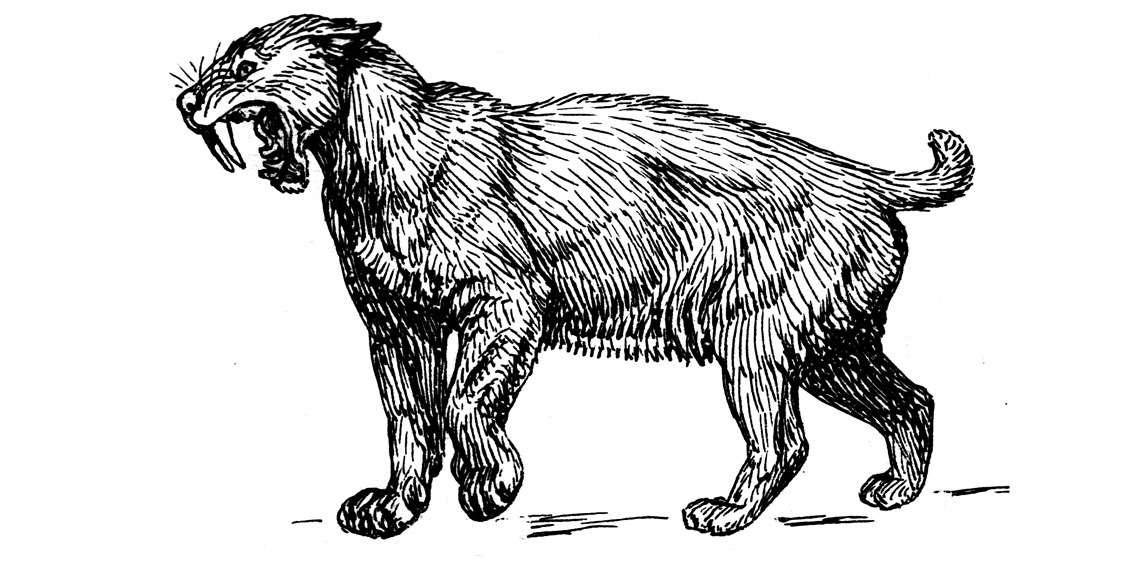

A saber-toothed tiger (Smilodon populator) that lived 100,000 years ago likely spent its last days limping across the northern plains of present-day Argentina. This is the conclusion of paleontologist Fernando Henrique de Souza Barbosa, based on research carried out at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and published in the journal Paleoworld in May. Barbosa examined the fossil of a forelimb bone called a metacarpus, measuring roughly 8 centimeters (cm) in length, the only part found in excavations of the skeleton of the largest terrestrial predator that ever inhabited South America.

The fossil had a series of alterations that he says are typical of osteomyelitis, a disease generally caused by the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. This infection often leads to swelling inside the bone, which would have made it difficult for the animal to use its paw. The only way to find evidence of the microorganism responsible for the infection would be to destroy part of the fossil, which the researcher chose not to do. The pathogen, which can also infect humans, was responsible for almost 200,000 hospitalizations in Brazil between 2009 and 2019. The infection starts in the skin and can progress to the bone marrow if left untreated, causing deformities, as happened with the saber-toothed tiger.

Barbosa’s Argentine colleagues invited him to analyze the excavated bone in 2010 based on his reputation as a specialist in paleopathology. This field of study looks at all alterations in fossilized bone, whether they were caused by diseases or not, including fractures, cavities, and protuberances. “Studying pathologies makes paleontology even more interesting, because it provides details about the animal’s habits and how it died,” says paleontologist Jorge Ferigolo of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), a pioneer of the field in Brazil.

Ferigolo notes that he has found few cases like this because the disease makes the bones fragile. “They break apart and disappear from the fossil record,” he explains. According to him, most human cases occur after accidents that lead to open fractures or after bone reconstruction surgeries.

Ferigolo explains that the infection can also start in the skin and reach the bones through the bloodstream within three to four weeks. It then spreads, causing tissue necrosis and loss. “In these cases, antibiotic treatment usually prevents further damage,” he says. But this first requires a proper diagnosis, which is often not made.

“It’s a rare find, especially in South America, where we find few saber-toothed tiger bones,” says Ana Maria Ribeiro, a paleontologist from UFRGS who was not involved in the research. Studies of other S. populator specimens found a femur fracture, spinal degeneration, a skull injury, and urinary stones. This type of infection had never been recorded before.

Fossils of the North American S. fatalis, a similar species, are much more common. At one site in Los Angeles, USA, paleontologists excavated more than 2,000 fossilized bones and identified deformities in the hips caused by unregulated cell multiplication, bone dysplasia, and various types of spinal alterations—but no osteomyelitis.

Barbosa has previously studied cases involving similar infections in giant sloths (Eremotherium laurillardi) and a mastodon (Notiomastodon platensis). A case of the disease was identified in a dinosaur fossil from the municipality of Ibirá in São Paulo, as described in an article published in Cretaceous Research in 2021 by paleontologist Tito Aureliano of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). There were also parasites in the dinosaur’s blood vessels.

Pearson Scott Foresman

Pearson Scott Foresman

Bones compared

To identify the Argentine saber-toothed tiger species based on the paw bone alone, Barbosa, currently at the State University of Amazonas (UEA), compared the sample with equivalent fossils from other felines that lived in the region, such as the cougar (Puma concolor) and the jaguar (Pantera onca), and with healthy specimens of S. populator. After comparing the diseased bone with a healthy one from the same species, he noticed that the former was thicker, with a protuberance of about 1 cm. In X-ray images, he saw that some areas were destroyed and others denser, typical of a serious infection.

“Looking at the photos in the article, you can make a confident diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis,” says Ferigolo, who has a degree in medicine and became interested in bones and their diseases while working as a radiologist in the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Ribeiro points out that the holes in the bone go from the marrow to the surface, through which pus was eliminated, weakening the tissue. “This is an animal that suffered, it could no longer move its paw and it must have had great difficulty walking and hunting,” says the researcher.

In 2012, an international group of scientists found Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a bison that lived in the US state of Wyoming 17,000 years ago. Laboratory tests identified fat molecules typical of these bacteria—the technique, Barbosa explains, is even more precise than DNA analysis for this purpose.

Pathology festival

The three paleontologists all agree that altered bones are much more common in herbivores, since there are more of them in nature and consequently in the fossil record—giant sloths and giant armadillos, for example. “The megafauna herbivores were large, five or six meters tall, and their weight caused the cartilage between the vertebrae to thin and their bones to fuse, compressing the nerve in between,” explains Ribeiro, who has studied such cases.

The researcher has seen many perforations in the carapaces of glyptodonts, indicating infestations by fungi, scabies, or flea-like insects that penetrated the skin and gnawed at the animal’s bone. Fractures to the carapace and tail were also common, probably the result of fights in which the giant armadillos struck each other with the club-like bones at the end of their tails.

“Joint diseases, such as arthritis and osteoarthritis, were very common in these armadillos, which made digging and fighting a tough task,” says Barbosa. Among giant sloths, he noticed that the problem was more frequent in older individuals.

Fossil pathologies can also be a cause of confusion when identifying species. A classic case involved a Neanderthal man excavated in La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France, in 1908. French paleontologist Marcellin Boule (1861–1942) reconstructed the skeleton, whose spine was curved forward like a quadruped’s. He concluded that the individual was an intermediary species between great apes and modern man. Further research, however, revealed that it was a senile individual with osteoarthritis of the spine and acute discopathy, a disease that degenerates the cartilage between the vertebrae of the spine.

Scientific articles

LUNA, C. A. et al. Osteomyelitis in the manus of Smilodon populator (Felidae, Machairodontinae) from the Late Pleistocene of South America. Paleoworld. Online. May 22, 2023.

AURELIANO, T. et al. Blood parasites and acute osteomyelitis in a non-avian dinosaur (Sauropoda, Titanosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Adamantina Formation, Bauru Basin, Southeast Brazil. Cretaceous Research. Vol. 118. Feb. 2021.