In Brazil, 9.4 million people have experienced sexual violence at some point in their lives. There are 1.8 million boys and men included in this figure, according to the 2022 National Health Survey (PNS), conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Data from the Ministry of Health indicate that 46% of girls who are victims of attacks report the cases while still adolescents. For boys, however, that number is only 9%. Globally, a study published in the journal Nature in October 2023 estimates that around 10% of men were subjected to some form of sexual abuse in childhood.

Researchers studying the subject state that such high levels of underreporting in comparison to women are related to stereotypes associated with masculinity and the low visibility that the problem has in society, which is also reflected in the scarcity of studies focused on understanding this type of violence.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual violence as sexual acts (or the attempt to obtain sexual acts) and unwanted comments and advances or other actions aimed against people’s sexuality, which also includes psychological intimidation, blackmail, and threats.

In his doctoral research defended in 2022 at the Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, psychologist Denis Gonçalves Ferreira, from the institution’s Center for Research on LGBT Human Rights and Health, performed a scoping review of studies on sexual violence against boys and men conducted in Brazil from 2015 to 2021. “Scoping reviews incorporate comprehensive searches in databases to map publications regarding a particular topic in the scientific literature,” explains researcher Maritsa Carla de Bortoli, from the Center for Health Technologies for the Unified Health System (SUS), at the Institute of Health in São Paulo, who also participated in the research. The results of this type of study can reveal the principal studies, areas of concentration, and groups working on the topic, among other possible connections.

Under the guidance of medical epidemiologist Maria Amélia de Sousa Mascena Veras, Ferreira’s analysis identified that 1,400 studies were conducted in Brazil on the subject of sexual assault, but only 53 of them investigated cases involving male victims. “In our study, we noted a lack of articles on sexual violence against boys and men in Brazil, as well as a dearth of studies with an exclusive focus on this issue,” says Ferreira, who is also a professor at the Centro Universitário Várzea Grande, in Mato Grosso.

The psychologist notes that the 53 mapped studies involved a total of 1.4 million people. “Among males, the groups most affected by sexual violence are men who have sex with men and those with sexual dysfunctions, with a prevalence of up to 71%,” the researcher observes. The survey showed that men who are victims of sexual violence are more prone to drug use, social isolation, unprotected anal sex, suicidal ideation, and sexual dysfunction.

Aline van LangendonckFerreira also reports that, of the 53 studies, six analyze cases of female aggressors, which the researcher says breaks with the concept that it’s only men who play this role. As with female victims, attacks against boys are usually carried out by people close to them, such as friends and family, and occur in the victim’s or aggressor’s home. “However, the analysis of case notifications points to a difference in comparison to girls and women. Violence against boys tends to be more long-term, as they hesitate longer before talking about the issue and reporting it, which means the crime can go on for years,” the researcher says.

Aline van LangendonckFerreira also reports that, of the 53 studies, six analyze cases of female aggressors, which the researcher says breaks with the concept that it’s only men who play this role. As with female victims, attacks against boys are usually carried out by people close to them, such as friends and family, and occur in the victim’s or aggressor’s home. “However, the analysis of case notifications points to a difference in comparison to girls and women. Violence against boys tends to be more long-term, as they hesitate longer before talking about the issue and reporting it, which means the crime can go on for years,” the researcher says.

Another difference, according to Ferreira’s study, is that boys are victims of sexual assault at an earlier age than girls. “Most of them suffered attacks before the age of ten, while among girls violence seems to be more frequent from preadolescence onwards,” he points out. These data are corroborated by the 2022 Brazilian Public Safety Directory. In rapes of those classified as vulnerable, i.e., children up to 13 years old, 46% of cases among boys occur in the 5- to 9-year-old age group, while among girls the highest incidence (55.8%) is recorded from 10 to 13 years of age.

Before starting on his doctorate, Ferreira says he was surprised by the number of male patients he saw in his office in São Paulo who reported having been victims of sexual assault. “However, the majority hadn’t sought psychological treatment for this violence, which had impacts that ended up appearing later, during the therapeutic process,” he says. Motivated by his experience as a psychologist and by the data he had collected for his dissertation, in 2021 he created an NGO, Memórias Masculinas, which focuses on providing online assistance to male victims of sexual violence. The psychological treatment format the NGO offers is psychological attending care, i.e., time with a qualified listener to comfort victimized men at the moment when suffering and memories of the event emerge. “We received more than 200 people from January 2021 through the end of 2023,” the researcher reports.

Another study Ferreira conducted involved a sample of 1,200 men from all over Brazil who answered an online questionnaire in 2002 to investigate their history of sexual assault. The survey showed that 70% of participants suffered noncontact sexual violence before the age of 11, such as exposure to sexual conversations and pornography, while 30% reported having been subjected to forced sex, that is, violent acts with penetration. “This means that the most prevalent violence among men is that which leaves fewer physical marks, which makes filing complaints difficult and contributes to underreporting,” he assesses.

Psychiatrist Saulo Vito Ciasca, coordinator of Espaço Transcender at the Butantã Health Center of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine (FM-USP), specializes in the care of transgender and homosexual children and adolescents who are victims of aggression. He says young people with gender variance and boys considered “effeminate” tend to be more frequent targets of sexual violence. “They are often seen as more vulnerable by attackers, who often claim that they raped them to ‘correct’ their sexuality,” he comments.

Furthermore, homosexual children and adolescents who have been raped are afraid of being held responsible and punished for the very violence they lived through. “In a similar manner to what happens with women when it’s said they were raped because of their cleavage or short skirt — an obvious example of machismo — gay boys who are attacked also blame themselves for being ‘effeminate,’” the researcher says.

Sexual violence against boys is more frequent before the age of 10 and tends to continue longer compared to similar abuse against girls

Another complex factor is that men who are victims of this type of violence can feel pain and pleasure at the same time during the sex act, causing involuntary stimuli in their reproductive organs. “This ends up being confusing for the victim, who may think that they didn’t suffer violence because they apparently felt pleasure, which can also generate feelings of guilt,” says Ciasca, who is also director of the lato sensu postgraduate specialization course in psychiatry at Cetrus-Sanar, a São Paulo company providing products and services to support medical students and professionals.

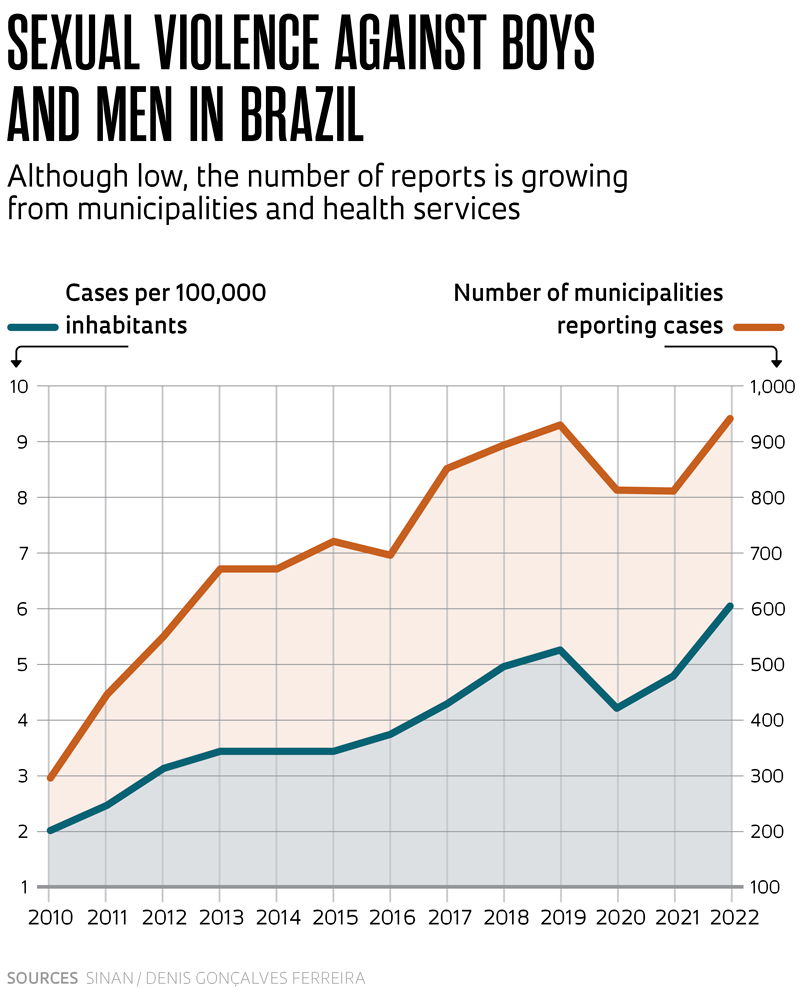

In other, unpublished research by Denis Ferreira of Santa Casa, a study whose results will be released in an article that is still in press analyzed data from the Notifiable Disease Information System (SINAN), the Ministry of Health, and the Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP). The survey identified an increase in reports of sexual violence against boys and men in all regions of Brazil between 2009 and 2022, especially in the Northeast and South and in the age group from 20 to 60 years. “As for race, all categories recorded an increase, with an emphasis on the brown-skinned group. The analysis by education level shows growth in every category, especially among men who are college graduates,” reports Ferreira.

The study also evaluated reports of rape among men and boys recorded in Public Security Departments nationally from 2017 to 2022 and found a 28.9% drop in these cases nationwide. On the other hand, in the same period, there was a 39.5% increase in reports of sexual violence against this same group by national health services. “These numbers indicate that cases were no longer being reported to the Public Security departments, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the psychologist observes.

However, the survey indicates that health service reports increased overall, despite the drop observed in 2020, with the rate of complaints filed regarding sexual violence against boys and men per 100,000 inhabitants increasing and reaching its peak in 2022 at 6 cases per 100,000 inhabitants (see graph). The number of municipalities that were reporting cases also increased, suggesting a greater geographic scope in the documentation of recorded cases.

Psychologist Jean Von Hohendorff relates that while treating a boy who had been a victim of sexual violence, the child told him that the worst part of the traumatic event — perpetrated by an adult male aggressor — was the systematic insults he began to receive from his own mother, questioning his masculinity. Hohendorff coordinates a research group investigating violence, childhood, adolescence, and the activities of protection and treatment networks, based at Atitus Educação, a higher education institution in Passo Fundo, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul. One focus of his research analyzes the relationships between masculine stereotypes and sexual assault.

In 2010, the psychologist completed his master’s degree at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), where his thesis research developed a psychological intervention model geared toward boys who had been victims of sexual violence. Written based on protocols used for girls at public health services in the city of Passo Fundo, the study was published as a book in 2014. “At the time, I noticed a lack of research on sexual assaults against boys and decided to delve deeper into the subject,” he says.

In treatment sessions conducted at the time with boys and adolescents who had experienced this type of violence, Hohendorff observed the patients had extreme difficulties in talking about the events. This resulted in his decision to further investigate the issue during his doctorate, also defended at UFRGS, in 2016. The fear of being questioned about their masculinity, together with the fact that the aggressor is often their financial provider, are among the reasons for victims’ resistance to addressing the issue, the researcher concluded.

Another group dedicated to supporting male victims of sexual violence, the Portuguese NGO Quebrar o Silêncio (Break the silence) calculates that — on average — it takes men 20 years to be able to report such attacks, and that in Portugal only 3.9% of cases are actually reported. According to the NGO, one in six men is a victim of sexual assault before the age of 18 in Portugal and only 16% of them admit to having been raped. “The first step in treating these victims is to enable them to talk about their experience. Only at that point is it possible to think about interventions,” Hohendorff says.

In 2019, the content platform Papo de Homem (Man chat) formed a partnership with the University of São Paulo Social Information Consortium (CIS-USP). As part of that initiative, 47,000 men were interviewed about issues involving masculinity. The survey showed, for example, that 37% of respondents said they had never talked about what it means to be a man, with 78% expressing the belief that they should not behave in ways that appear feminine and 57% that they can’t express emotions. Among other results, the initiative gave rise to the documentary O silêncio dos homens (The silence of men), directed by Luiza de Castro and Ian Leite. “Men are educated to be able to defend themselves and be strong. Many, when they suffer sexual violence, feel that they have failed in this regard, and have failed to fulfill their role in society,” says Ferreira, from Santa Casa.

In his doctoral dissertation defended in 2023 at the School of Architecture and Urbanism (FAU) at USP, (with FAPESP funding), architect and historian Pedro Beresin Schleder Ferreira researched books on moral education for men produced or translated in Brazil between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. “During this period, the country was going through a process of social transformation and bourgeois masculinity became associated with a conception of modern civilization,” he says.

Ferreira points out that at the time, both femininity and masculinity were being reconfigured. Thus, in works such as A arte de formar homens de bem (The art of training good men), by Domingos Jaguaribe Filho (1847–1926), or O poder da vontade (The power of will), by Samuel Smiles (1812–1904), the ideas that men needed, for example, to master their emotions and be productive were promoted. To expand the discussion, Ferreira argues for an increase in research into behavior manuals related to the construction of masculinity in Brazil, in the same way that such works have focused on the role of women in society.

Psychiatrist Carmita Abdo, founder and coordinator of the Sexuality Studies Program at USP’s Hospital das Clínicas, estimates that for every ten cases of sexual violence seen at the hospital, only one of the victims is a man. Abdo, who is also the former president of the Brazilian Psychiatric Association, observes that, when there are suspicions of aggression, the health professional must report it to the police. “However, I think it’s essential to separate treatment in the healthcare system from the legal authority,” she argues. On the one hand, professionals aren’t always sure that there was any aggression; on the other hand, victims of violence might avoid healthcare services for fear that such policies could result in legal proceedings.

The psychiatrist adds that many people repeatedly attacked during childhood and youth may become either victims or aggressors in adulthood. “Without support and adequate care, some adopt sexual violence, experiencing it as something natural,” she states.

Aline van Langendonck

Aline van Langendonck

An article published in Nature in October 2023 defines childhood sexual abuse as “exposure before the age of 15 to any unwanted sexual contact.” It is a type of violence that causes both immediate emotional and physical trauma and has consequences that can last a lifetime and impact future generations.

The study views these attacks as a risk factor for subsequent experiences with perpetrating violence on intimate partners and indicates that people exposed to sexual assault in childhood have a 45% greater risk of suffering disorders due to alcohol use and are 35% more likely to develop depression. The results were obtained through a systematic review conducted in seven electronic databases of intimate partner violence and childhood violence.

With these damages in mind, professor Andreza Marques de Castro Leão, from São Paulo State University (UNESP), Araraquara campus, conducted a study from 2017 through 2020 in public schools in the state of São Paulo, with FAPESP funding. The goal was to understand preventive actions and identify school activities that can help prevent such abuse, including screening films and documentaries, creating games, writing songs, and reading books, among other approaches.

Leão also develops extension projects in schools together with teachers, managers, parents, and students. For one of the initiatives, students hung sheets of paper on which they had written their feelings and doubts about sexuality and violence on a clothesline. “Using these approaches, we talk about the body, personal rights, self-esteem, physical touching, good and bad secrets, and sexual solicitation. We address the need to say no to suspicious, uncomfortable, and invasive situations, among other aspects,” she says.

The researcher explains that many cases come to light through activities. “In one school in São Paulo State, after a learning activity, a boy with teary eyes got up, gave me a hug, and left sadly,” she comments. In addition to talking to the child, she contacted the team at the Social Assistance Reference Center (CRAS), enabling them to uncover that he was being abused.

Another situation she identified was the history of a 12-year-old boy who had been raped by a classmate’s mother. “When he reported what happened, his friends cheered, saying that he was lucky to have been able to begin his sex life with an experienced woman,” she says. “It took months for the victim to realize that he was being abused, and this occurred during an activity that I was conducting at school on the subject,” she reports.

Finally, Leão points out that the Child and Adolescent Statute (ECA) contains relevant, specific articles, namely: article number 13, which states that cases of violence must be reported to the Guardianship Council; article number 245, which determines that anyone who does not file such a report is liable for negligence; and article number 56, according to which directors of educational institutions must make these notifications.

Currently, the researcher works in partnership with municipalities in the state of São Paulo and continues developing activities to combat sexual violence in schools. “These initiatives make it possible to alert students to the existence of this type of aggression, as well as how to identify and refuse sexual violence and request help. Since such violence generally occurs within the family, sometimes the adult who can identify that it’s happening — or gets alerted by the student — is the teacher,” she concludes.

Projects

1. Measures to prevent child and adolescent sexual violence: Analyzing the training and knowledge of early childhood and elementary education professionals (nº 17/07350-8); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Andreza Marques de Castro Leão; Investment: R$22,666.00.

2. Constructing home comfort: Daily life, consumption, and distinction between middle market sectors of São Paulo (1870-1920) (nº 17/25133-4); Grant Mechanism PhD Fellowship; Supervisor Ana Lucia Duarte Lanna (USP); Beneficiary Pedro Beresin Schleder; Investment R$223,335.02.

Scientific articles

FERREIRA, D. G. et al.Violência sexual contra homens no Brasil: Subnotificação, prevalência e fatores associados. Revista de Saúde Pública 57:23. 2023.

SPENCER, C. N. et al. Health effects associated with exposure to intimate partner violence against women and childhood sexual abuse: A burden of proof study. Nature Medicine. 29. pp. 3243–58. 2023.

CAMPOS, A. et al. Prevalência de violência sexual com contato e sem contato contra homens brasileiros e fatores associados a sexo forçado. Saúde em debate. Vol. 47, no. 138. July–Sept. 2023.

VICENTE, A. et al. Violência sexual infantojuvenil e os indicadores de gênero. Ensino & Pesquisa. Vol. 19, pp. 254–68, 2021.

Book

HOHENDORFF, J. V. et al. Violência sexual contra meninos – Teoria e intervenção. Curitiba: Juruá Editora, 2014.

Republish Aline van LangendonckFerreira also reports that, of the 53 studies, six analyze cases of female aggressors, which the researcher says breaks with the concept that it’s only men who play this role. As with female victims, attacks against boys are usually carried out by people close to them, such as friends and family, and occur in the victim’s or aggressor’s home. “However, the analysis of case notifications points to a difference in comparison to girls and women. Violence against boys tends to be more long-term, as they hesitate longer before talking about the issue and reporting it, which means the crime can go on for years,” the researcher says.

Aline van LangendonckFerreira also reports that, of the 53 studies, six analyze cases of female aggressors, which the researcher says breaks with the concept that it’s only men who play this role. As with female victims, attacks against boys are usually carried out by people close to them, such as friends and family, and occur in the victim’s or aggressor’s home. “However, the analysis of case notifications points to a difference in comparison to girls and women. Violence against boys tends to be more long-term, as they hesitate longer before talking about the issue and reporting it, which means the crime can go on for years,” the researcher says.