Reproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBE

A Burle Marx project for the Copacabana promenade, Rio de JaneiroReproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBERecognized for the revolution he fostered in Brazilian landscape architecture, and recognized internationally for projects he designed in numerous countries, Roberto Burle Marx, a native of the city of São Paulo, would have been 110 years old in 2019. During the first half of this year, two exhibitions are honoring his work, one at the Brazilian Museum of Sculpture and Ecology (MUBE) in São Paulo, and another in New York. Both draw attention to some little-discussed aspects of his legacy. Throughout his career, which began in the 1930s and which he pursued actively until his death in 1994, Burle Marx developed more than 2,000 landscaping projects, which are today an integral part of the daily lives of cities such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Recife, Miami, and Caracas. He excelled at many other activities, working as a painter, jeweler, botany researcher, and ecologist, and left behind significant works in the various fields in which he produced.

Although he figured as a revolutionary in the history of Brazilian landscape design, Burle Marx wasn’t an isolated genius, but rather, an artist sensitive to the spirit of an era that changed the landscape of the arts and culture in Brazil. As the recent exhibitions show, from the beginning his artistic production incorporated two essentially modernist traits that are also present in other art and literature of the period: the renewal of aesthetic research, and the valorization of local elements. In his gardens, these elements can be recognized as an attempt to distance the work from European standards and search for new forms based firmly on Brazilian roots.

Examples of such pioneering works are concentrated in the city of Recife, where he was director of the Parks and Gardens Division of the Department of Architecture and Urbanism from 1935 to 1937. There were about 40 projects, one of them being the Euclides da Cunha Square—”the first essentially Brazilian public garden and the most innovative idea of landscaping,” observes architect Ana Rita Sá Carneiro, a professor at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), and coordinator of the university’s Landscape Laboratory.

Reproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBE

Water garden at the Itamaraty Palace, in BrasíliaReproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBEFor this project, Marx carried out research on the history of the region and its ecosystem, based mainly on his reading of Rebellion in the Backlands, by Euclides da Cunha (1866–1909). With his proposal to bring the vegetation of the Caatinga (semiarid scrublands) into the city, he implemented the use of cacti and stones, elements previously seen as unsuitable for a garden. This established, as Sá Carneiro maintains, “a new way of thinking about public space using elements from the local landscape, interpreted according to the artistic principles of painting, music, and botany.”

Moreover, the cactus is a symbol of Burle Marx’s connection to his times, observes Guilherme Mazza Dourado, an architect and historian of landscaping who has been researching Marx’s work for more than 20 years. He recalls the presence of cacti in paintings such as Abaporu, by Tarsila do Amaral (1886–1973), and Paisagem brasileira (Brazilian Landscape), by Lasar Segall (1889–1957), as well as in the poem O cacto (The Cactus) by Manuel Bandeira (1886–1968). “Marx’s work isn’t isolated, it is immersed in a great cultural melting pot of exchange and dialogue,” says the researcher. “This is not only true of Brazil, but also of international culture,” he adds, highlighting the interest his work inspired in American landscape designers Thomas Church (1902–1978) and Garrett Eckbo (1910–2000), who also sought to modernize techniques through aesthetic research and thus established contact with the Brazilian designer, recognizing an affinity.

Burle Marx’s correspondence shows his concern for the preservation of the environment

American interest in Burle Marx is long recognized, as Dourado demonstrates in his postdoctoral research on the landscape designer’s correspondence history, developed at the School of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (FAU-USP). In 1954, for example, some of his work was on display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, then moved on to nine other cities throughout the United States. For this June, the Botanical Garden of New York has programmed The living art of Roberto Burle Marx. Breaking with the panoramic view traditionally directed toward the landscape designer’s oeuvre, the exhibition will center on three areas: an outside garden created by architect and Marx disciple Raymond Jungles, a greenhouse with plants either named after the designer or discovered by him in his expeditions, and a selection of his abstract paintings, drawings, and tapestries. “This attention to three aspects of his work is, I believe, a new way of approaching the different artistic contributions he made during his career,” says art historian Edward Sullivan, a professor at New York University (NYU) and the exhibition’s director. A specialist in Latin American art, he has been researching Burle Marx’s artistic production since the 1990s and, like Dourado, emphasizes the importance of its relationship to the context of his times. “Throughout the years, I’ve learned a lot by thinking of him as a barometer of the aesthetic changes that have taken place in Brazil,” he says. He takes as an example Marx’s abstract phase, which he began in the late 1950s, working in dialogue with other artists of the concrete and neo-concrete movement.

In the essay “Roberto Burle Marx: A total work of art,” part of a book on the landscape artist to be released as part of the New York exhibition, Sullivan argues that Burle Marx’s artistic production—which he calls “static works”—can in some cases represent the essence of his activity, since, as a landscape designer, he produced “living art” that wasn’t always possible to preserve. It’s no accident that this task intrigues and engages these experts. Dourado is part of the team that produced the official request—still under consideration—to register the Sítio Burle Marx with the UNESCO World Heritage List, while UFPE’s Sá Carneiro uses the Landscape Lab to develop programs with the city of Recife for restoring and conserving the city squares Marx designed. The main challenges involve the need for skilled labor. “There is no garden without a gardener,” states Sá Carneiro. “It’s imperative to train professionals to preserve the garden as a monument.”

Reproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBE

Cariátide (Caryatid), bronze sculpture, 1990Reproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBEAttention to the climate

One of the main aspects of Burle Marx’s activity was his concern for the environment. “The city is in nature; its gardens show that one has to understand nature as something that surrounds everything,” says Sá Carneiro. “It’s not just about representing nature within the city, but about a vision that seeks to preserve it so that people can understand and respect it,” she explains. Dourado also recognizes the didactic function in Marx’s creations: “When he brings a plant from another environment to a park in the city, he draws attention not only to its unique beauty, but also to the need for preservation. He wants to show people that it’s worth having that plant near you—and also to preserve it in its original locations.”

To support his creations, at the age of six the landscaper started an important collection of plants that today includes 3,500 species. Brought together at the site that bears his name, Sítio Burle Marx is a property of more than 400,000 square meters in Barra de Guaratiba, in Rio de Janeiro, now linked to the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). Recognized as one of the most important in the world, the collection is the result of tireless work that included expeditions to a variety of Brazilian biomes. The site is the landscape designer’s supreme achievement in the opinion of Dourado, who also highlights the importance of the art collection established there, which includes Burle Marx’s own production as well as a diverse selection of art objects. For Sullivan, the place also represents the “culmination of his unique and personal imagination,” although it relies on an ongoing collective commitment in order to continue to embody his creative spirit. “A garden is obviously an organic entity whose life extends beyond the vision of its creator, and of those responsible for its maintenance,” he notes.

Reproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBE

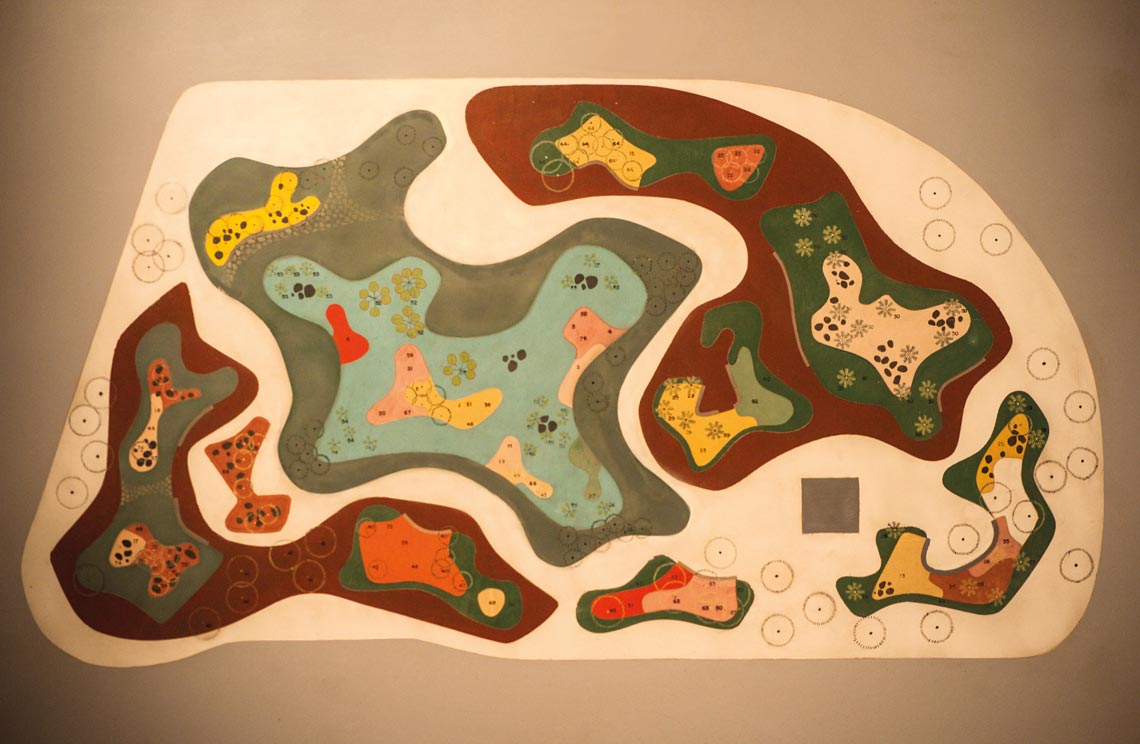

Automotive paint on particleboard shows the landscape architect’s project for Flamengo Park in RioReproduction / Leonardo Finotti / Exhibition: Burle Marx: Art, Landscape, and Botany, MUBEMarx’s concerns about the environment manifested themselves in other ways, which have only recently begun to be revealed. “His activity as a critic and environmental advocate,” says Dourado, “is still little known.” Based on the landscape architect’s correspondence, he underscores how Burle Marx publicly condemned politicians and business for advocating a model of “progress” based on the destruction of nature. Evidence of this activity is his reaction to the forest burning promoted in southern Pará State, with the objective of opening areas for pasture for an agribusiness project of Volkswagen Brazil. In a letter sent in 1976 to Wolfgang Sauer, then president of the company, the landscaper expressed his indignation: “You said that the fire used on the occasion burned exclusively shrubs, weeds, and other types of undergrowth, never trees. I don’t believe in trained fire. In addition to ‘weeds,’ it must also have burned ‘noisy’ macaws, ‘filthy’ armadillos, ‘ferocious’ jaguars, ‘poisonous’ snakes, large trees—without a doubt—and perhaps even some ‘treacherous’ Indians.” “50 years ago, Burle Marx was already disputing the uncontrolled advance of agriculture and livestock farming over the natural landscape, insistently arguing questions that we haven’t been able to resolve to this day,” the researcher adds.

Project

Leaves in motion: The letters of Burle Marx (nº 12/50319-0); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Grant; Principal Investigator Vladimir Bartalini (USP); Scholarship Beneficiary Guilherme Onofre Mazza Dourado; Investment R$247,203.54

Scientific articles

Dourado, G. M. (2017). Mirrors on the self: Seeing Burle Marx through his letters. Paisagem E Ambiente, (39), pp. 15–39.

Sá Carneiro, A. R. (2017). Fifth Door: The garden design as a landscape. Cadernos de Arquitetura e Urbanismo Cidade-Paisagem. Recife: Patmos Editora, Vol. 2, pp. 78–95.

Sá Carneiro, A. R., Castel-Branco, C., & Silva, J. (2016). Burle Marx in Recife: Restoring the Guararapes Airport garden as a heritage site. Paisagem E Ambiente, (37), 53–71.