At the beginning of the twentieth century, she defied conservative criticism by writing about love, loneliness, anguish, and feminine desire—she wrote lines like “Amar! Amar! E não amar ninguém!” (Love! To love! And not love anyone!). After a tumultuous, tragic life, which included three marriages, two divorces, and accusations of incest and nymphomania, as well as committing suicide on her own birthday at the age of 36, the Portuguese writer and poet Florbela Espanca (1894–1930) became popular in her country of origin but found academic support in Brazil. “Since the 2000s, Brazilian researchers have played a lead role in academic studies on Florbela, globally,” says Portuguese researcher Ana Luísa Vilela, a professor at the Center for Studies in Letters at the University of Évora, in Portugal.

Vilela says this is largely due to the work of Portuguese literature professor Maria Lúcia Dal Farra, who began teaching at the University of São Paulo (USP) in the 1970s, moved to the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and retired from the Federal University of Sergipe (UFS) in 2019. During her qualifying research to obtain tenure at UFS, Dal Farra pored over a manuscript filled with poems, short stories, and notes written by Espanca in the 1910s, which she located during a research trip to Portugal. “It’s a gem, a kind of prehistory of Florbela’s literary career,” says Dal Farra. Her work generated the book Trocando olhares (Exchanging glances), a compilation of Espanca’s writings, which was published in Portuguese by Imprensa Nacional/Casa da Moeda in 1994, with an introduction, editing, and notes by the Brazilian researcher. It was followed by titles such as Afinado desconcerto (contos, cartas, diário) (A finely tuned disquiet [stories, letters, diary]), edited by Dal Farra and released in Brazil by the Iluminuras publishing house in 2004, and Sempre tua. Correspondência amorosa 1920–1925 (Yours Always; Love Correspondence 1920–1925), put out by the same publisher in 2012.

Wikimedia Commons

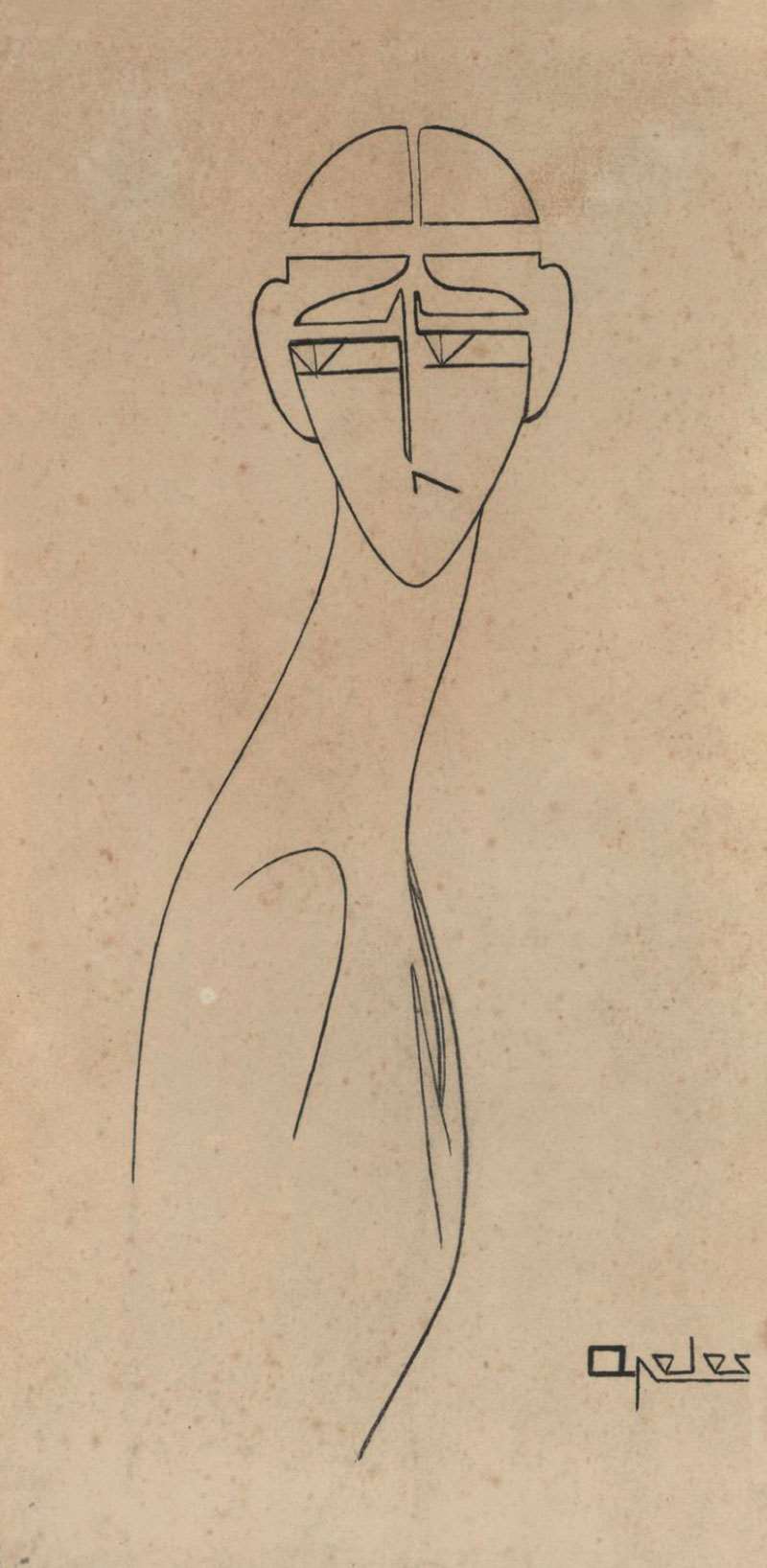

Drawing of the Portuguese writer by her brother, Apeles EspancaWikimedia Commons“Maria Lúcia not only produced an important bibliography, which became a reference for Espanca studies, but also supervised academic projects and created an important research group on Espanca,” says Vilela. The researcher refers to “Figurations of the feminine: Florbela Espanca et al.,” which operated between 2010 and 2021 at UFS. “This group helped to galvanize a new generation of Espanca researchers in Brazil,” says Portuguese professor Cláudia Pazos Alonso, from the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom, and author of the book Imagens do eu na poesia de Florbela Espanca (Images of the self in the poetry of Florbela Espanca) (Imprensa Nacional/Casa da Moeda) released in 1997 in Portugal as the result of her doctoral thesis at Oxford.

Jonas Leite, from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) was a member of this group, and author of the recently released De Florbela às Florbelas: Do mito literário à invenção de uma personagem-escritora (From Florbela to the Florbelas: From literary myth to the invention of a writer as fictional character) (EDUPE). In the book, the result of his doctoral dissertation at Paraíba State University (UEPB), Leite analyzes five plays about Florbela written in Brazil and Portugal, as well as the novelized biography Florbela Espanca, a vida e a obra (The life and work of Florbela Espanca) (1979), by Portuguese writer Agustina Bessa-Luís (1922–2019), and a set of poems written by Dal Farra in the writer’s honor. “Florbela’s literary work is indeed tangled up in the intricacies of her life story, but, above all, it’s essential to acknowledge the importance of her literature and her unquestionable talent. Hence the need for studies on her highly complex life,” says Leite.

Between reality and fiction

Born in Vila Viçosa, in the Alentejo region of Portugal, Florbela d’Alma da Conceição Espanca began to write verse as a child, but her official literary debut came in 1919 with the publication of Livro de Mágoas (Book of sorrows) (Tipografia Maurício). In 2019, Fabio Mario da Silva, another member of the UFS research group and a professor at the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE), organized an international conference with Vilela to celebrate the centenary of the work (which comprises 32 of Espanca’s sonnets), as well as to honor Dal Farra. Held in Portugal, the conference resulted in two publications launched this year: A crítica e a poetisa: Estudos sobre Maria Lúcia Dal Farra (The critic and poet: Studies on Maria Lúcia Dal Farra) (Libertas Editora and Sol Negro Edições/Arc Edições) and 100 anos do Livro de mágoas. Releituras da obra de Florbela Espanca (100 years of the Book of Sorrows: Rereading the works of Florbela Espanca) (Sol Negro Edições/Arc Edições), with articles by researchers based in Brazil, Portugal, Spain, England, and France.

While she was alive Espanca would publish just one more work, Livro de “sóror Saudade” (Sister Saudade’s book) (Tipografia A Americana), in 1923. “These two books have a thematic connection. In the first, the writer personifies a princess in a castle, in the second, a nun in the cloister, both waiting for their Prince Charming who never arrives. Through them she speaks about the pain engendered by misunderstanding and the lack of loving correspondence,” explains Renata Junqueira, a professor of Portuguese literature at São Paulo State University (UNESP), Araraquara campus.

I want to love, love hopelessly!

Love just for love’s sake:

Here… beyond…

And this one and that one,

the Other and everyone…

Love! To love!

And not love anyone! Remember? Forget? I’m indifferent!…

Hang on or let go?

Is it bad? Is it good?

Anyone who says you can love someone

For an entire lifetime

—it’s because they’re lying!

(excerpt from Charneca em flor)

Both titles came out at the time when modernism was emerging in Portugal via poets such as Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935) and Mário de Sá-Carneiro (1890–1916). “But Espanca didn’t affiliate with any literary schools. Her poetry is unclassifiable, has its own distinct personality and draws from various sources, such as symbolism,” observes Silva, who worked with Alonso on the most recent re-release of some of the author’s work in Portugal. “Not to mention how difficult it was for a woman to carve out space in Portuguese modernism, which was essentially masculine and sexist—for example, there wasn’t one woman working on the Orpheu journal [1915], the initial milestone of the movement in Portugal.”

Because she wrote sonnets, critics relegated Espanca to the nineteenth century. “Which is absurd, because she was a woman who not only lived during the first three decades of the twentieth century, but also portrayed the female concerns of that time,” Junqueira says. An example of this is her posthumous book Charneca em flor (Heathland in flower) (Livraria Gonçalves, 1931). “This book is more sensual than her previous work, and here Espanca praises the liberation of the woman’s body. It was an innovation for Portuguese poetry,” adds the scholar, who has been focusing on Espanca’s work since graduate school. Dal Farra agrees. “She was one of the first to write about female desire in Portuguese literature,” she observes.

The two scholars believe it’s thanks to this pioneering spirit that the writer has in the end sustained a dialogue with later generations of Portuguese poets, especially from the second half of the twentieth century forward, such as Adília Lopes, author of the book Florbela Espanca espanca (Florbela Espanca beats) (1999). In Brazil, Junqueira can see this dialogue in authors such as Dal Farra herself, who won the Jabuti Literature Prize with the book of poems Alumbramentos (Illuminations) (Iluminuras publisher, 2012), and the writer and poet Maria Mortatti, a professor at UNESP’s Marília campus and author of the book of poems Breviário amoroso de sóror Beatriz (Sister Beatriz’ Amorous Breviary) (Editora Patuá, 2019).

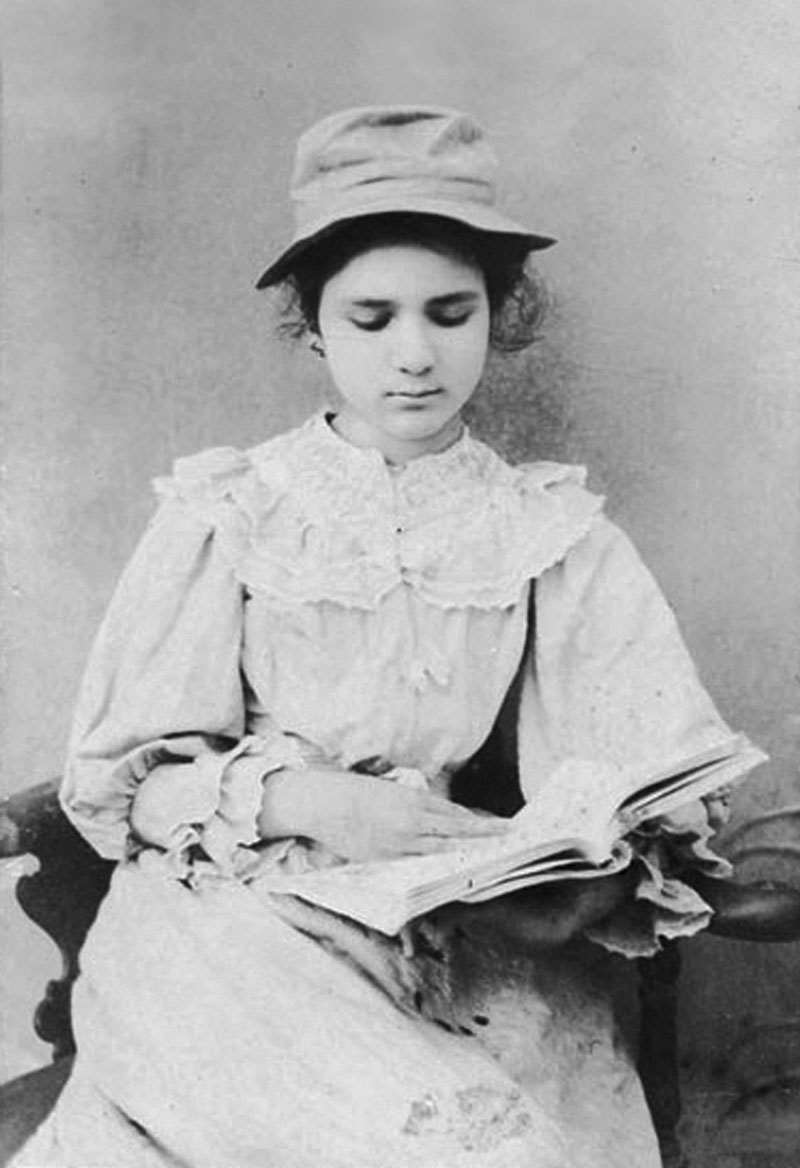

João Maria Espanca / National Library of Portugal

Dead at the age of 36, Espanca wrote her first verses during childhoodJoão Maria Espanca / National Library of PortugalIn addition, Florbela’s life and work inspired plays, the feature film Florbela (2012)—a Portuguese production directed by Vicente Alves do Ó—as well as songs in Brazil and Portugal, Leite points out. For example, Raimundo Fagner, the singer-songwriter from the state of Ceará, set some of the Espanca’s sonnets to music, such as Fanatismo, from the Livro de “sóror Saudade,” released on the album Traduzir-se (1981), which became one of his greatest hits. “Even those who’ve never read Florbela are likely to be acquainted with her, without knowing it, through music,” says Andreia de Lima Andrade, a professor at UFRPE.

“But she received hardly any recognition during her own life. Florbela began achieving popularity in Portugal shortly after her death due to the initiative of the Italian poet Guido Battelli (1869–1955), a professor at the University of Coimbra,” says Dal Farra. “Battelli met Florbela in 1930 and decided to sponsor the publication of Charneca em flor. With the poet’s unexpected death and the book about to come out, he resorted to a marketing strategy that exploited Florbela’s suicide to attract the attention of readers and the press.”

As a result, the newspapers of the time raised suspicions about the writer’s private life. Among the rumours was the idea that Florbela allegedly had an incestuous passion for her only brother, Apeles Espanca (1896–1927). After he died in a plane crash, she honored his memory with the book of short stories As Máscaras do destino [The masks of fate], published posthumously by Marânus publishing in 1931; her second book of short stories, O dominó preto (The black domino), wouldn’t be published until 1982, by Livraria Bertrand. There was also talk about the fact that her birth was the result of an extramarital relationship between her father, the antique dealer and photographer João Maria Espanca (1866–1954) and Antónia da Conceição Lobo (1879–1908).

So far I haven’t

known myself, I thought it was

me, but I was not

The one that in my

verses I had described

As clear as a spring

and like the day.

But what I was not

I didn’t know

and even if I had known,

I did not say…

Eyes fixed on shimmering chimera, It walked behind me…

And didn’t see me!

It was looking for me —

poor crazy thing!

(excerpt from Charneca em flor)

Battelli’s strategy worked from a financial standpoint and Charneca em flor was a commercial success. “However, from then on the connection between Espanca’s biography and her work became fixed. In addition, while gaining notoriety, Florbela became a target of the Salazar dictatorship, with support from the Catholic Church,” observes Dal Farra, referring to the regime that officially lasted between 1932 and 1974, but noting that Portugal had already been under a conservative, authoritarian government since the 1920s. “In that moralistic context, which defended the ideal of a chaste, pure, and domestic woman, Florbela ended up a persona non grata: she was persecuted, branded as a debauched woman, and even a prostitute. They tried in vain to erase her work.” Not merely by chance, a bust carved in the writer’s honor in 1931, by Portuguese sculptor Diogo de Macedo (1889–1959), was only inaugurated in the city of Évora 18 years later, after much public controversy.

The researchers believe this confusion between reality and fiction damaged the critical reception of Espanca’s work. “For many years, the critics themselves have grandly continued, with few exceptions, identifying biographical events between the lines of all of her work,” says Junqueira, author of Florbela Espanca, uma estética da teatralidade (Florbela Espanca: An aesthetics of theatricality) (Editora UNESP, 2003). “It should be noted, however, that in each of her books, Florbela wears a mask. While in the Livro de ‘sóror Saudade’ she takes on the guise of a nun, in Charneca em flor she embodies the role of a seductive sorceress who masterfully manipulates love, passion, and eroticism.”

This emphasis on her personal past is now behind us, experts say. “The biography written by Agustina Bessa-Luís, released in 1979, opened up new possibilities for understanding Florbela as a character and not the author of an autobiographical work,” argues Jonas Leite. “This is a path that has been followed by most researchers since the 1980s.” Such is the case for Andrade, at UFRPE, who is author of the thesis “From dominoes to masks: The autofictional game in Florbelian short stories,” defended in 2019 at UEPB. Andrade believes the Portuguese writer and poet had been constructing a kind of autofictional literary game.

Public domain. Archive and digitization of João Bacelar Espanca, provided by Fabio Mario da Silva

Florbela Espanca (in the flower hat) in 1918 with friends, her brother Apeles (in the middle, looking to the side), and her first husband, Alberto Moutinho (between Apeles’ legs)Public domain. Archive and digitization of João Bacelar Espanca, provided by Fabio Mario da SilvaPioneering works

According to Dal Farra’s research, the first dissertation on Espanca’s work was done by Maria de Lourdes Barreiros Lopes, in 1945, at the University of Lisbon. The second academic work appeared 14 years later, as a master’s thesis by Maria Manuela Moreira Nunes, at the University of Coimbra, also in Portugal. “In the late 1980s, when I became interested in researching Florbela, she was practically forgotten in Portuguese universities,” recalls Alonso, of the University of Oxford. “She’s still being studied in various other countries today, perhaps more than in Portugal.” One of the reasons, suspects Vilela, is her great popularity among readers. “She is what’s called a ‘poet of the people’; studied in elementary school, and known by everyone, from taxi drivers to the president of Portugal, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, who chose a poem by Florbela to be recited in 2020 before the official speeches for the Day of Portugal, Camões and the Portuguese Communities, celebrated on June 10th. Maybe that’s why academics have considered her a ‘simple’ author, and not very complex, which, in my view, is a mistake,” she says.

Dal Farra believes Espanca’s work must have been introduced to Brazilian academia by the Portuguese intellectual Jorge de Sena (1919–1978), who went into exile in Brazil in 1959 and began teaching at the institution now known as UNESP, initially at the Assis campus and then in Araraquara. “The first bibliographic survey on Florbela’s treatment in literary academia was conducted at UNESP in Araraquara by researcher Carlos Alberto Iannone, in the 1960s,” says Farra. “Another pioneer is Zina Bellodi, who began editing works on Espanca in the 1970s and defended her doctoral dissertation “Florbela Espanca: Discourse of the Other and Image of the Self,” in 1987, also on the Araraquara campus.”

Today, the CAPES theses and dissertations catalog records 59 academic works on the author, conducted in various Brazilian universities from 1992 to 2020. “But there is still a lot to study about Florbela Espanca. It would be possible to delve deeper, for example, into her prose production, in this case the short stories, letters, and diary, which have been eclipsed by her poetry,” says Andrade, from UFRPE.

At the moment, Henrique Marques Samyn, from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), awaits the release of Esparsos de Florbela Espanca (The scattered works of Florbela Espanca), scheduled for next year, in Portugal. The book, done in partnership with Silva, from UFRPE, brings together stories, aphorisms, poems, and even unpublished verses written by a young Espanca in 1907, on the back cover of her physics book, while she was still in elementary school. “This material was scattered amongst sources such as newspapers and manuscripts. It was a mining job,” says Samyn. Another release scheduled for 2022, also in Portugal, is the Dicionário Florbela Espanca, organized by Silva and Leite, at UFPE. The work, which is being overseen by Dal Farra, features more than 100 entries prepared by around 80 researchers from countries such as France, England, the United States, and Portugal, including entries by, for example, José Carlos Seabra Pereira, a professor at the University of Coimbra, who has studied the author since the 1980s. “Florbela still has a lot to say to us in the twenty-first century,” concludes Silva.

Books

DAL FARRA, Maria Lúcia; VILELA, Ana Luísa; SILVA, Fabio Mario da; FINA, Rosa (ed.). 100 anos do Livro de Mágoas. Releituras da Obra de Florbela Espanca. Natal: Sol Negro Edições/ARC Edições, 2021.

VILELA, Ana Luísa; SILVA, Fabio Mario da; PEDROSA, Inês; FINA, Rosa (ed.). A crítica e a poetisa: Estudos sobre Maria Lúcia Dal Farra. Recife: Libertas Editora (1st edition), Natal: Sol Negro Edições/ARC Edições, 2021.

LEITE, Jonas. De Florbela às Florbelas: Do mito literário à invenção de uma personagem-escritora. Recife: Edupe, 2021.