Limited, incomplete, unequal: this is what Brazilian education was like at the beginning of the twentieth century. “Few public schools in the cities were attended by children of middle-class families. The wealthy hired tutors, generally foreigners, who homeschooled their children. Alternatively, they sent them to one of the select secular or religious private schools operating in the country’s capital cities as boarding and day boarding schools […]. Across the country’s vast interior there were a few remote rural schools, most of which were staffed by teachers without any professional training, who served populations scattered over huge areas,” says educator Paschoal Lemme (1904–1997), member of an educational reform movement that aimed to transform this reality, in an article from 1984 in the Brazilian Journal of Pedagogical Studies.

Known as “Escola Nova” or “Escola Ativa,” this movement had been spreading throughout Europe and the United States (as the New Education Movement) since the end of the nineteenth century. In Brazil, it gained traction mainly after the First World War, due to American influence, and it advocated for free, compulsory, and universal public education. The belief that children should be central to the learning process was another branch of the movement. According to North American philosopher and educator John Dewey (1859–1952), one of the main theorists of Escola Nova, this would be the “Copernican revolution” of education: “It is a change, a revolution, not unlike that introduced by Copernicus when the astronomical center shifted from the earth to the sun. In this case, the child becomes the sun about which the appliances of education revolve; he is the center about which they are organized,” writes Dewey in the book The School and Society: The Child and the Curriculum (University of Chicago Press, 1915). “In this new conception of what a school should be, which is a response to the exclusively passive, intellectualist, and transmissive tendencies of traditional schools, all work must be underpinned by spontaneous, joyful, and fruitful activity, aimed at satisfying the needs of the individual himself,” states the Manifesto dos Pioneiros da Educação Nova (Manifesto of the Pioneers of Educação Nova), a document that introduced the revolutionary movement within Brazil.

In March of 1932, the manifesto was published by various press outlets, featuring the signatures of 26 renowned educators and intellectuals, such as Anísio Teixeira (1900–1971), who at the time was Director of Education for the Federal District; Júlio de Mesquita Filho (1892–1969), owner of the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo; writer Cecília Meireles (1901–1964); and educator and sociologist Fernando de Azevedo (1892–1974), editor of the manifesto and the first signatory.

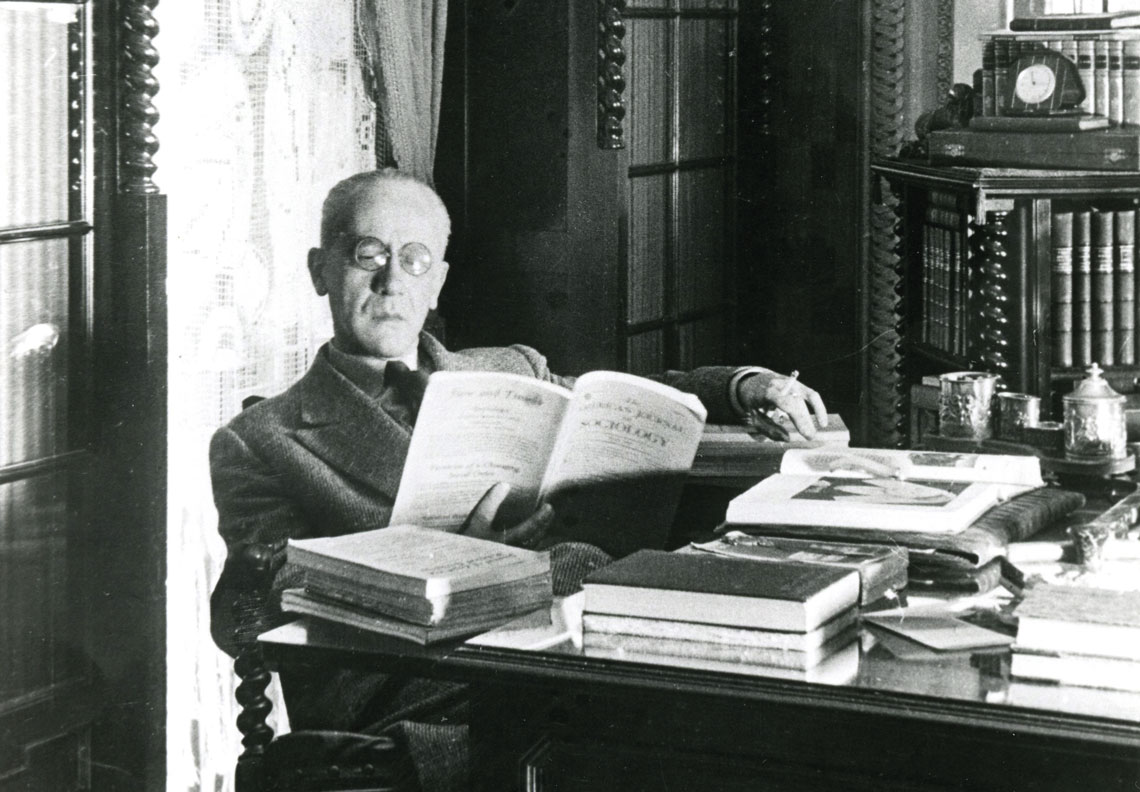

Fernando de Azevedo’s archive Fernando de Azevedo, author of the Education Code, in a photo from the 1950sFernando de Azevedo’s archive

Azevedo would also be responsible for drafting Decree no. 5.884, the Education Code, introduced in April of 1933 to organize education within the state of São Paulo under the theoretical guidelines laid out in the manifesto. According to educator Rosa Fátima de Souza Chaloba, a history of education professor at the Araraquara campus of São Paulo State University (UNESP), the Code significantly influenced education in São Paulo. According to her, placing the child at the center of the educational process and “learning by doing,” through observation, research, and experience, is a pedagogical concept that still resonates today. “But the document was most impactful in its defense of public schools and universal access to education.”

The right to education

The Manifesto of the Pioneers of Educação Nova, recognized education as an “essentially public service” and defended “the right of each and every individual to a comprehensive education.” When Fernando de Azevedo took over as the Director of Education for the Federal District, he worked to make this right a reality in the state. He knew that he might not have much time to implement the reforms he was pursuing, as São Paulo had been experiencing significant political instability since the Revolution of 1930. “From October of 1930 to December of 1932, there were eight different governors and three different Directors of Education,” lists Chaloba. Azevedo was only in office for six months (from January to July of 1933), but he managed to establish a new system for São Paulo education, in a decree featuring 922 articles. Under his supervision, two committees worked to draft the Education Code, which was completed and approved in less than three months.

“Wherever there are 200 children in need of a school, within a 2-kilometer radius, a school group will be created,” stipulated article 267 of the Education Code. There was an urgent need to increase the number of school sites. According to the 1920 School Census, 74.2% of the state’s children were illiterate. “It took a long time to change this scenario. Until around 1950, almost half of São Paulo’s children were not in school,” says Chaloba. According to the researcher, the insufficient number of schools to meet the demand for education made it difficult to adhere to the principle requiring school attendance during much of the twentieth century.

CAPH / FFLCH / USP CollectionThe Caetano de Campos Normal School, transformed in 1933 into an institute for training university professorsCAPH / FFLCH / USP Collection

To address this challenge, Azevedo established a new school construction policy in the Education Code, creating the School Buildings and Facilities Service. “At the time, most of the schools operated out of rented buildings, and the state spent a lot of money on rent,” recalls educator Ariadne Lopes Ecar, a researcher for the Alfredo Bosi Chair of Basic Education at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Advanced Studies (IEA-USP). According to the researcher, many of these buildings, which were ill equipped to house schools, were unable to offer the activities and pedagogical structure that the Education Code prescribed, according to the parameters of an Escola Ativa: a school library and museum in each teaching unit “from preschool to upper grades,” an educational radio and film service, music and choir classes, medical and dental care.

Decree no. 5.884 also mandated the establishment of nursery schools in factories for the workers’ children. According to Chaloba, the Anuário do ensino do estado de São Paulo 1936-1937 (Directory of education in São Paulo State 1936–1937), organized by the Director of Education, Antonio Ferreira de Almeida Júnior (1892–1971), cited only four nursery schools in factories, aided by the state.

One of the Code’s highlights is how it organized the Institute of Education, created just two months prior (in February of 1933), by Decree no. 5.846, which transformed the Caetano de Campos Normal School into a training institution for university professors. According to article 629, the purpose of the Caetano de Campos Institute of Education was to train primary and secondary professors, in addition to school directors and inspectors, and to host training courses for members of the teaching profession. It was the first institution to provide teacher training at a university level in São Paulo.

Helio Nobre and José Roseal / Paulista MuseumThe Code pushed for the expansion of the so-called school groups in central São Paulo, such as the one in São José do Rio Preto, built in 1916, and the one in Itatinga, from 1910Helio Nobre and José Roseal / Paulista Museum

In addition to the School for Teachers, the Caetano de Campos Institute featured a library and special schools: kindergarten, elementary school, and high school. In 1934, the School for Teachers became part of the newly created USP. And thus, the plan set out in the Manifesto of the Pioneers, which stated that the university was “at the apex of all educational institutions” and “destined, in modern societies, to develop an increasingly important role in the formation of elite thinkers, scholars, scientists, technicians, and educators,” was put into practice. According to followers of the Escola Nova, teachers at all levels should be part of this intellectual elite, preparing themselves “in university courses, at colleges, or at mainstream schools for upper education incorporated into universities.”

From ideal to reality

According to Chaloba, São Paulo’s educational model was replicated throughout the state, which eventually had 126 educational institutes, training teachers according to Escola Nova guidelines. The Escola Nova ideals, however, clashed with reality. “Escola Nova enchanted most teachers, but the teaching structure remained traditional, even in the way that schools were physically organized, with desks facing the teacher’s desk, as the focal point. And few school sites were able to install the infrastructure that Escola Nova required,” states philosopher Dermeval Saviani, retired professor and employee at the University of Campinas’s School of Education (UNICAMP). He argues that, despite Fernando de Azevedo’s efforts, the Escola Nova ideals were basically implemented in experimental schools or at upper-class educational institutions.

According to Ecar, of IEA-USP, of the 15 technical services established by the Education Code (in addition to the Buildings Service, there were those dedicated to installation of libraries and museums, radio and film, cultural extension for adults, etc.), the most successful service was the Scholastic Social Works Service. The director of this service was responsible, for example, for supporting the Parent-Teacher Association and organizing school funds and cooperatives to support the neediest students. “Social intervention was a way of ensuring attendance and preventing dropouts,” says the researcher. The School Hygiene and Health Education Service also achieved some success in the area of medical and dental care: “Not all schools had clinics, but there were doctors and dentists circulating the network,” says Ecar.

Butantan Institute’s Collection / Memory CenterStudents and professors at the Padre Anchieta Normal School visit the Butantan School Group, in 1936Butantan Institute’s Collection / Memory Center

“The Code is historically symbolic because of the reform it proposed, but it was difficult to put into practice. In order to implement the planned services, it would have been necessary to hire many more people, which was not possible in all schools. Even so, directors and professors who were enthusiastic about Escola Nova ideals made personal efforts,” explains Chaloba.

The Escola Nova principles remained the official guidelines for São Paulo education until 1971, when the military government reformed the structure and curriculum of basic education. “It was quite a drastic reform, implemented in an authoritarian climate. It significantly increased the number of positions, while creating instability within the teaching profession,” says Chaloba. According to Saviani, this reform was also underpinned by a major conceptual change: “The reform of the 1970s shifted the axis of education.” He explains that, if Escola Nova sought to shift the focus of teaching from the teacher to the student, now both were subjugated to methods and techniques aimed at efficiency and productivity. This was known as “pedagogical technicism.” “Pedagogical technicism is the transposition of industrial systems into teaching,” he concludes.

The 1971 reform created vocational courses in high schools, but the government later repealed the measure, which required that investments be made in infrastructure. Half a century later, high school education curriculum was again discussed within the context of the High School Reform (Law no. 13.415/2017), which introduced subjects related to the job market, to the detriment of basic education.

Butantan Institute’s Collection / Memory CenterStudents work in the garden at the Butantan school, in São Paulo, which combined subjects from the official program with rural activitiesButantan Institute’s Collection / Memory Center

Carmen Sylvia Vidigal Moraes, a professor at USP’s Faculty of Education and coordinator of its Education Memory Center (CME-FEUSP), recalls that the reform, which strayed from the ideals proclaimed in the Manifesto of the Pioneers, established a schism between general propaedeutic education (introductory, preparing students to progress to higher education) and professional education, aimed at preparing them for the job market.

The Education Code only suggests the possibility of bifurcating high school to “prepare for professions, preferably of an intellectual or practical and mechanical basis.” “The duality of education would not only persist in the state of São Paulo but would later be adopted at a federal level through the Organic Education Laws of 1942, whose template derives from the high school education system defined in the São Paulo State Education Code,” notes Moraes.

According to Chaloba, Brazil managed to expand access to schools, but still faces the challenge of improving access to knowledge. Quality, universal, and free public education, which inspired the 1933 Code, and the structuring of comprehensive and consistent high school education remain ideals to be pursued.

Republish