A variant of the Oropouche (Orov) virus, which causes Oropouche fever, identified in January in the northern region of Brazil, may be responsible for the current spread of the disease throughout the country. As of August 19, the Brazilian Ministry of Health registered 7,653 cases (the figure for 2023 was 831), including four cases of microcephaly and the death of two women, 21 and 24 years of age, neither of whom had any underlying conditions. With similar symptoms to those of dengue, these are the first recorded cases globally due to this type of virus. On August 3, the Health Ministry confirmed the first fetal fatality from the virus, transmitted from mother to son in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. To the 5th of the same month, São Paulo State had confirmed five cases.

A study at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), published in July on the medRxiv platform, illustrated that the variant known as Orov_BR-2015-2024, or new Orov, when inoculated in human cells, produces 100 times more virus in a 48-hour period than the first strain isolated in Brazil in the 1960s. When cultivated, this formed pits up to 2.5 times bigger in the cell layer.

“New Orov is capable of replicating more quickly and evading some of the antibodies produced by the immune system in response to previous infections,” observes virologist José Luiz Módena, coordinator of the UNICAMP team. “As it is very quick to multiply, it can likely reach higher quantities in the blood of infected people or animals, potentially favoring infection of the transmitting insect.” The main transmitter currently is the maruim or paraensis midge (Culicoides paraensis), whose larvae feed on organic material found in forests, parks, and plantations, usually on the outskirts of cities.

Módena and his team examined blood samples from residents of Manaus, Amazonas, with similar symptoms to those of dengue, collected in 2024. Of the 93 samples, 10 were found to be from people with Oropouche fever. Two were sequenced and identified as the new Orov, first described in January by virologist Felipe Naveca, of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) Amazônia, in Manaus.

Scott Bauer, USDA Agricultural Research ServiceMaruim, transmitter of OropoucheScott Bauer, USDA Agricultural Research Service

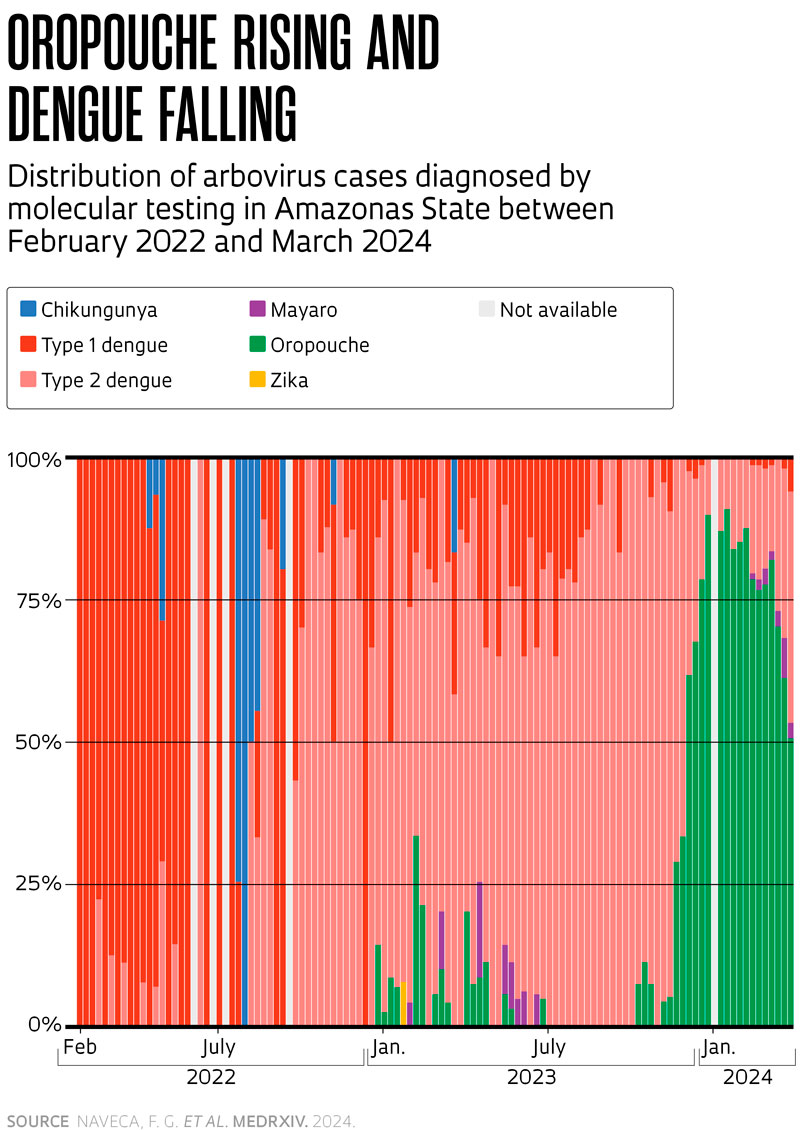

The new strain was identified after sequencing 400 viruses collected during the outbreak in the Amazonian states of Rondônia, Roraima, and Acre between 2022 and 2024, as detailed in a preprint published by Naveca on medRxiv on July 24. “New Orov emerged between 2010 and 2014 after genetic rearrangement of three different viruses that circulated in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia,” says Naveca.

“This is a virus with a high capacity for killing the cells it infects,” says virologist Eurico Arruda, of the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine (FMRP-USP), where studies into Oropouche began in the 1990s. As Arruda detailed in a 2017 article in the Journal of Medical Virology, the virus infects the leucocytes—immune system blood cells—by which it spreads through the organism. In a 2021 study published in Frontiers in Neuroscience, Arruda’s team and that of Adriano Sebollela, also of USP at Ribeirão Preto, demonstrated that Orov can multiply in sections of human brain in the laboratory, causing an inflammatory response harmful to the organism.

Researchers interviewed by Pesquisa FAPESP agree that the new variant is not the only factor driving the Oropouche fever epidemic. Rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns due to climate change may have widened the maruim vector occurrence area. Moreover, deforestation in Amazonia may well have driven the insects into urban areas.

Intensification of diagnostic testing by the national network of the Central Public Health Laboratory (LACENS) has also contributed to an upturn in the number of recorded cases. “We started paying more attention to Oropouche when we found that a large proportion of outbreaks was not due to dengue, an illness with which it is easily confused,” states infectologist Julio Croda, of the Campo Grande FIOCRUZ facility, who believes that the high numbers and geographical distribution of cases, with confirmed reports across 20 of the 27 Brazilian states, constitute an Oropouche fever epidemic in Brazil (see map). “This situation is very different to local outbreaks that occurred in the North of Brazil up to last year,” he comments.