The Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP) is celebrating its 50th anniversary with a reformulated research pipeline that better addresses societal needs, and a funding strategy that balances public and private funding from sources that include the three levels of government, funding agencies, international organizations, corporations, and third-sector organizations. Created during the military dictatorship (1964–1985), and with a portfolio of approximately 500 scientific investigation projects completed to date—including pioneering studies in fields such as population studies, policy, the labor market, and inequalities—the center remains an important think tank for political, economic, and social issues and is today one of Brazil’s leading research institutions in the humanities.

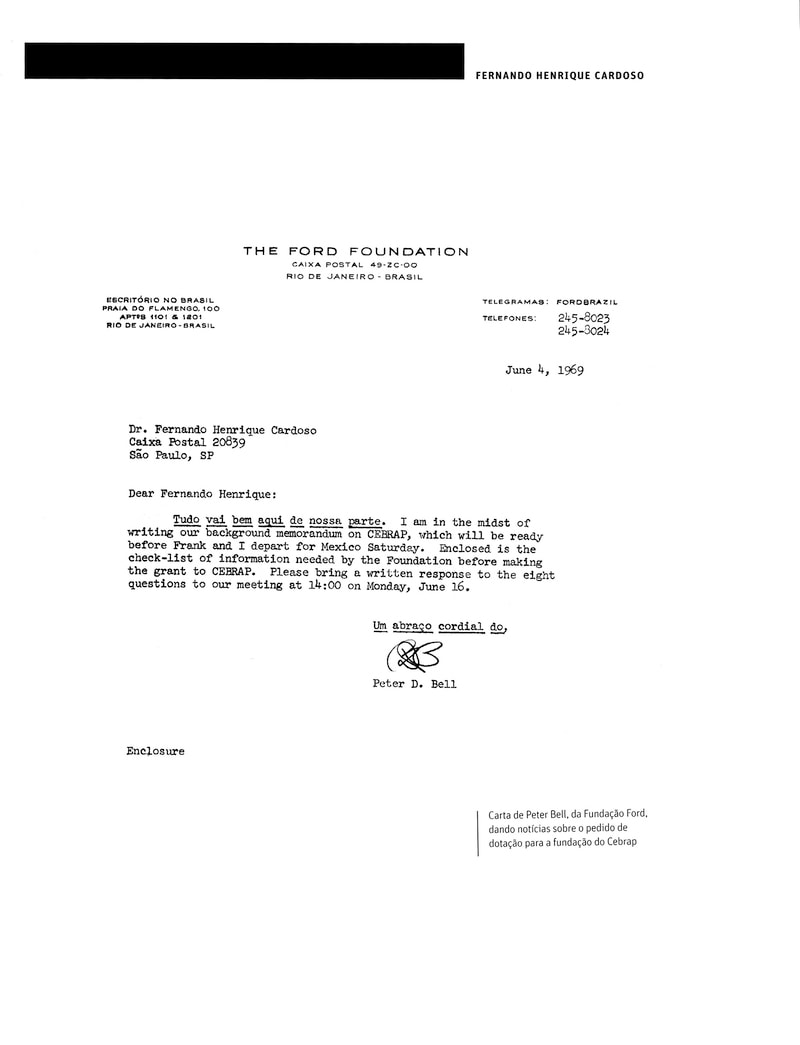

CEBRAP was founded in 1969 by a multidisciplinary group of professors who had lost their positions at universities due to political persecution, among them sociologist Fernando Henrique Cardoso, philosopher José Arthur Giannotti, demographer Elza Salvatori Berquó, and sociologist and demographer Cândido Procópio Ferreira de Camargo (1922–1987), all from the University of São Paulo (USP). In 1975, the center received a financial boost when an endowment fund of US$3.47 million (in current figures) was established with grant money from the Ford Foundation. “The foundation was looking to set up research institutions in Brazil to prevent a massive flight of intellectuals as had occurred in Argentina,” says Giannotti, a professor at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH) at USP. In an interview this year for a video celebrating the center’s 50th anniversary, former Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso recalls how funding for the center was arranged through Peter Bell (1941–2014), an American human rights advocate who had joined the Ford Foundation office in Rio de Janeiro in 1964.

Engaging with the private sector supports the design of project proposals that are in the public interest and can generate funding

CEBRAP continued to receive funding from the Ford Foundation and, to a lesser degree, from the MacArthur Foundation and the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP) until the mid-1990s. The money was used to defray administrative expenses and to pay a fixed staff of 20 researchers, who retained employment at the center regardless of the number of research projects in progress at any given time. “Foundations like Ford and MacArthur, while being liberal by the American definition of the term, were progressives who advocated for democratic values. They supported a number of civil-society organizations against the authoritarian context of Latin American dictatorships,” explains political scientist Adrian Gurza Lavalle of FFLCH, who served as scientific director at CEBRAP between 2008 and 2010.

Sociologist Angela Alonso, a professor at FFLCH who has served as president of CEBRAP over the past four years, says part of the endowment fund was used in the 1980s to purchase commercial properties in São Paulo. These properties were leased and the rent was used towards operating expenses until the mid-2000s, when they were sold for approximately R$3 million and the proceeds reallocated to short-term investments. Another portion of the endowment fund was used in late 1976 to purchase the center’s current offices in Vila Mariana. The decision to move from rented to owned offices came after a bomb attack that year on the house used as office space in Higienópolis.

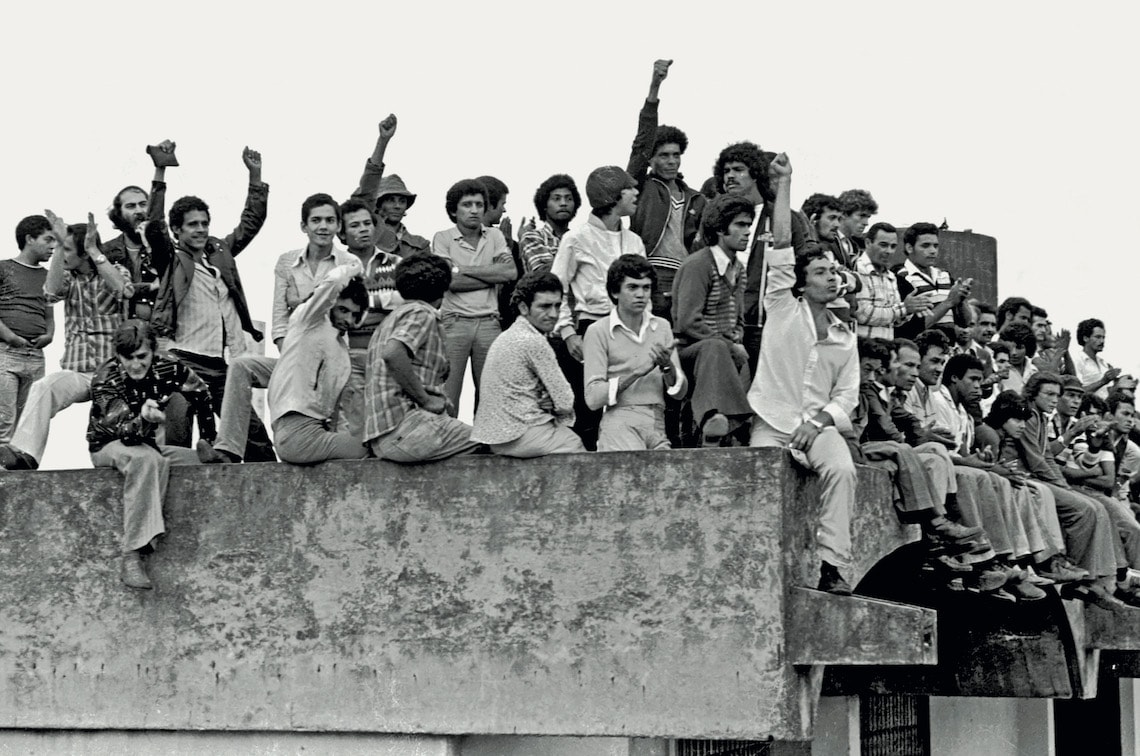

Juca Martins / Olhar Imagem

Research at the center investigates the role of social organizations in building democracy. In the photo, a steelworkers’ union rally in the ABC area (1979)Juca Martins / Olhar ImagemAlonso notes that under the organization’s bylaws, the principal of the endowment can only be used if previously authorized in a meeting of the board of trustees and audit board, and only in situations that are deemed critical, such as if the center is unable to maintain its administrative activities or pay its staff. “Other than in these circumstances, the center is only permitted to spend the amount by which returns on the endowment fund exceed inflation,” he says.

A turning point

After relying primarily on international funding for several years, the center faced new challenges following Brazil’s redemocratization in the mid-1980s. Although the return to democracy meant the end of political pressures on some members, and new fronts of research—one being the new political conjuncture and its implications for civil society and urban life—it also meant that the center would have to reformulate its funding strategy. Because Brazil was no longer considered a country in a situation of vulnerability, funding from international institutions was gradually withdrawn and funneled elsewhere in Eastern Europe, Africa, and Central America. Political scientist Fernando Limongi, a professor at FFLCH, recounts how when he was appointed as president of CEBRAP in 2001, the only source of institutional funding remaining was FINEP. “This compelled a reorganization of the center,” he recalls. “Our research staff could no longer be permanent, and the center became reliant on revenue derived from research projects. We created a common fund drawing from project overheads, which has since been used towards defraying administrative expenses,” explains Limongi. Meanwhile, international foundations also adopted a new governance model that prioritized projects with real-world applications and measurable outcomes, as opposed to the essentially academic studies which were then prevalent at CEBRAP.

Léo Ramos Chaves

The south side of São Paulo: urban planning research explores topics such as inequality and mobilityLéo Ramos ChavesIn addition to its conventional studies—primarily funded by public research-funding agencies—and applied research and advisory services for government agencies, CEBRAP added new research programs for the private sector and third-sector organizations to its portfolio. “Private-sector research has gained increasing weight in our activities over the previous 10 years. We have successfully developed projects for companies looking to address societal problems, including urban mobility research for Itaú, social-impact research for Natura, and legislative development research for Valor Econômico,” says sociologist Carlos Torres Freire, who has held the position of scientific director since 2015. Today, 35% of the center’s funding derives from funding agencies such as FAPESP, the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq)—FAPESP alone has provided 442 research and training grants since 1962, mostly since the 2000s. Another 15% of the center’s budget comes from international grants, and 20% from government partnerships for projects such as georeferenced poverty surveys; technology transfer for data acquisition on slums; demographic assessments; and urban planning initiatives. Public-interest research for the private sector accounts for another 18% of funding, with the remaining 12% deriving from services provided to third-sector organizations.

Anthropologist Paula Montero, a professor at FFLCH who served as president of CEBRAP from 2008 to 2015, explains that the center needs to have at least 20 ongoing research projects at any given time to stay in the black. It currently has 28. Approximately 20% of the revenue from these projects goes to operating expenses. CEBRAP’s governance structure is composed of a president, an administrative director and a scientific director. Fundraising activities, which involve responding to calls for proposals, and setting up partnerships with nongovernment organizations (NGOs), governments, and corporations, are managed by the scientific director and the heads of each of the center’s 15 research departments.