In November 2018, while walking along Caniçal beach, in the municipality of Lourinhã, in Portugal, known for having been the home of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, amateur paleontologist Filipe Vieira saw what appeared to be fossils encrusted in sedimentary rocks, which were covered at high tide. He was able to collect some fragments and sent them to Portuguese paleontologist Alexandra Fernandes, of the Lourinhã Museum. “What caught his attention were the dark teeth of a pterosaur, which contrasted with the lighter rocks,” says Fernandes. With Brazilian paleontologists, he led the analysis of the findings that suggested it was a new species of pterosaur, Lusognathus almadrava, the first described in Portugal, according to the article published in September in the scientific journal PeerJ.

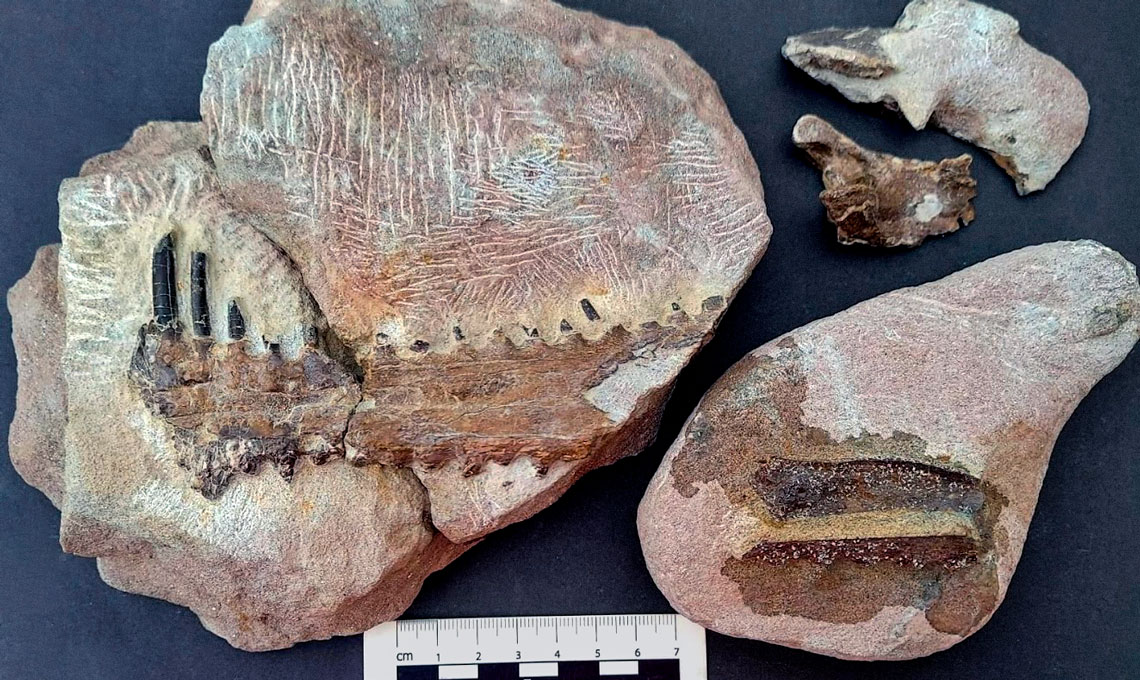

The winged reptile must have lived in the region around 149 million years ago, during the Jurassic period. The rocks, extremely hard and compact, proved hard work for the museum team that excavated the fossil fragments in March 2019. “It was necessary to saw the rocks in the few hours in which the tide was low,” reports Fernandes. The researchers were able to remove the front part of the L. almadrava jaw, with 29 teeth and fragments of another two loose teeth. The fossil also included three fragmented vertebrae from the neck.

Victor Beccari / Nova University Lisbon

A fossil preserved parts of the jaw and neckVictor Beccari / Nova University LisbonThe spatula-shaped snout, around 20 centimeters (cm) long and 5 cm wide, the slightly horizontal dentition in the format of a comb, as well as the pronounced cavities where the teeth are housed (dental alveoli), allowed the researchers to infer that it belonged to the subfamily Gnathosaurinae. “Its teeth reached 23 millimeters (mm) in length and were about 5 mm wide, more robust and thicker than those of the other species of the subfamily,” observes Fernandes, who is doing a PhD in the Department of Earth Sciences and Environment at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, in Germany.

These characteristics signal a diet composed mainly of fish. “Its expanded jaw indicates that this animal probably opened its mouth to get water with whatever was in it; the liquid would drain out the sides and the teeth retained the prey,” explains Brazilian paleontologist Alexander Kellner, director of the National Museum at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (MN-UFRJ), who took part in the characterization of the new species and is one of the coauthors of the article.

For that reason, the species was given the name almadrava, the name of a traditional Portuguese fishing trap. Lusognathus comes from the Latin lusus, in reference to Lusitania (the name of the area of Portugal in Roman times), and gnathus, meaning “jaw.” This feeding habit led the researchers to conclude that the species would have lived in shallow estuarine areas, tidal flats, marshy coastal areas, or even inland lakes. Based on the fossil fragments found, they also estimated that the winged reptile would have had a wingspan of 3.6 meters (m), which would have made it a large animal—in general, pterosaurs at this time measured between 1.6 m and 1.8 m from one wing tip to the other, whereas those from the Cretaceous (between 145 and 65 million years ago) reached much more than 3 m, argue the researchers in the article. Because of this new development, they suggested that this growth of the winged reptiles may have begun earlier than previously assumed and could have contributed to pterosaurs eventually occupying a different ecological niche than their competitors the birds. Additionally, their large size may indicate an ecosystem rich with prey.

Miguel Moreno-Azanza / Nova University Lisbon

Paleontologist Alexandra Fernandes in the fieldMiguel Moreno-Azanza / Nova University LisbonDespite being the first species of pterosaur described in Portugal, these are not the first fragments found in the country. Fossils of other winged reptiles, such as teeth and parts of a femur, as well as traces of footprints have been found since the 1950s, but because they were very fragmented it had not yet been possible to identify which species they belonged to. “One of the reasons for the difficulty is that the bones of these animals are hollow, more fragile, and the types of rocks in the country appear not to preserve them so well,” says Fernandes.

Kellner adds that the characteristics of the site where the fossil was found, a coastal area, can also interfere in the preservation of these fragile bones, because the rocks that contain them are subject to the continuous movement of the sea, which contributes to faster erosion. “But where there is one, there may be more. I hope to be able to carry out fieldwork in the region. The discovery has left us excited,” says the Brazilian, elected in June to the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon.

Scientific article

FERNANDES, A. E et al. A new gnathosaurine (Pterosauria, Archaeopterodactyloidea) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal. PeerJ. 11:e16048. Sept. 2023.