At 12 years of age, Rafinha, a mixed-breed dog, is already experiencing the effects of aging. He suffers from calcification in the lumbar vertebrae, which causes chronic pain. While the condition is irreversible, he is fortunate to be under the care of a dedicated and knowledgeable owner, veterinarian Cláudio Fanella, who now has an additional resource to help alleviate his suffering: an app designed to assess pain in animals. VetPain was launched in December last year by researchers from the School of Veterinary Medicine at São Paulo State University (FMVZ-UNESP), Botucatu campus. The result of a FAPESP-funded research project, the program is now available for free on Android mobile devices. While awaiting its release on iOS, it can be accessed at Animal Pain.

Fanella explains that he discovered the app when taking Rafinha for acupuncture sessions at UNESP, a service offered at the institution under the supervision of veterinarian Stelio Pacca Loureiro Luna, the researcher behind VetPain. Although Fanella has been using the app for only a month, he is already seeing positive results. “The app helps me better assess the level of pain and determine the right time to administer analgesics,” he says. “The tool gives me more confidence in decision-making.”

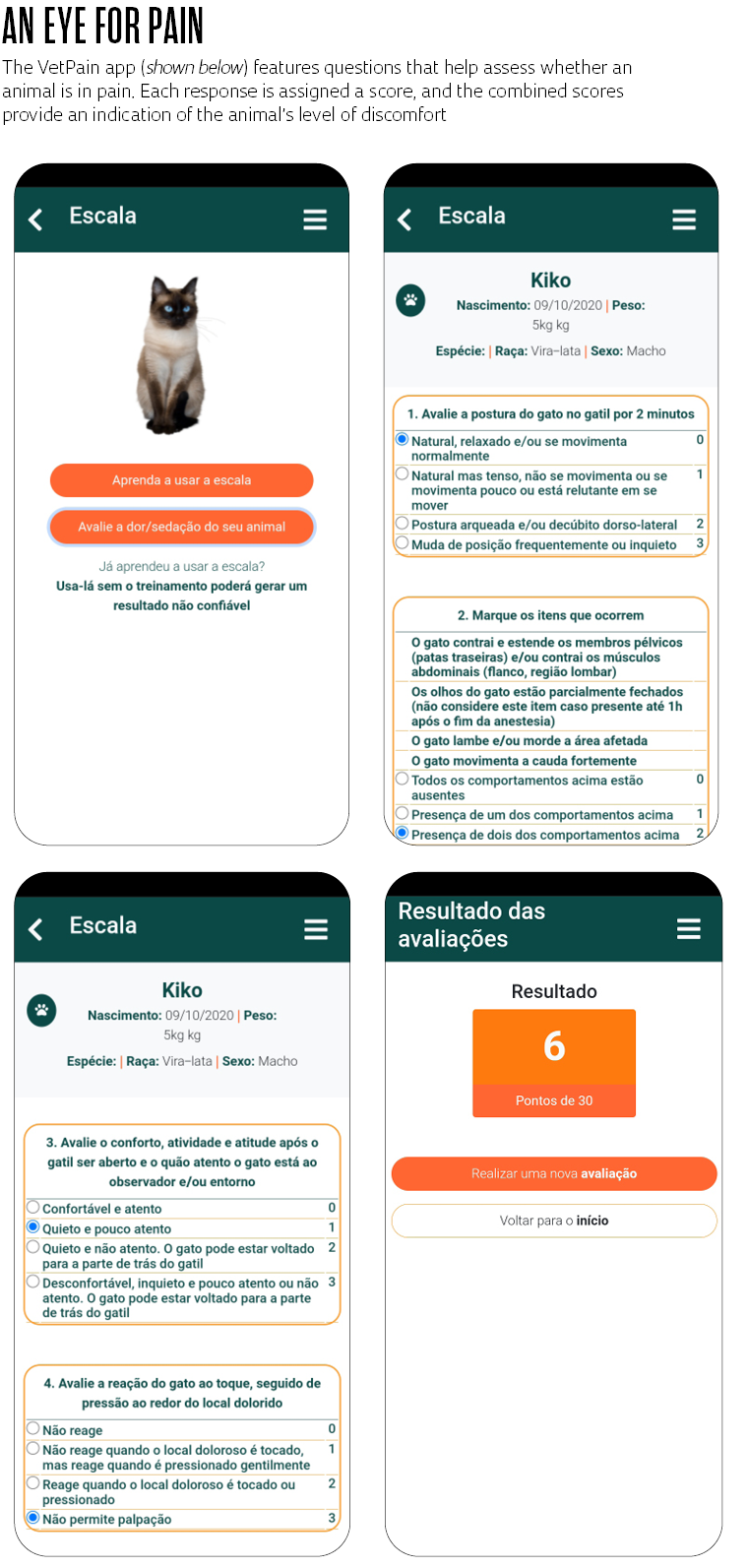

Fanella believes that VetPain is particularly useful because it encourages owners to observe their animals. The app evaluates pain through indicative behavior. Luna explains that VetPain works like a multiple-choice test. Users are presented with a series of questions to assess characteristic signs of pain, such as posture, level of activity, and reaction to being touched in the affected area. Users select the answers that best describe their animal. Each answer yields a score on a scale ranging from no pain to intolerable pain. The app automatically calculates the score and indicates whether or not the animal needs pain relievers.

As a guide for users, the app provides instructional videos demonstrating the behaviors exhibited by animals when in pain. Before administering the questionnaire for their own animal’s condition, users can take training sessions to assess their ability to use the scale based on 10 test videos. With this training, even laypersons can administer the test with confidence, says Luna.

However, some experts, such as Rosa Maria Cabral, coordinator of the Center for Veterinary Anesthesiology and Pain Studies at the School of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine of the Federal University of Lavras (FZMV-UFLA) in Minas Gerais, have reservations about the app’s use by laypeople. “Assessing animal behavior is subjective and relies on the experience of the examiner,” she explains.

She notes that certain behaviors associated with fear or anxiety, for example, can be mistaken for signs of pain. Her main concern regarding nonprofessionals using the app is pain relievers being administered without a veterinarian’s prescription. “Some of the analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs commonly prescribed for humans, such as paracetamol and diclofenac, are toxic to animals and can be deadly,” she cautions.

According to veterinarian Flávio Vieira Meirelles from the School of Zootechnics and Food Engineering at the University of São Paulo (FZEA-USP), an animal observed to be in pain needs to be examined to diagnose the underlying cause. “When the cause is already known and diagnosed, then, and only then, should pet owners administer drugs prescribed by the veterinarian, using the prescribed dosage,” he explains.

For Fanella, as long as pets are taken to the veterinarian whenever there are signs of pain, the app can serve as a highly useful educational resource. “It’s great for people who are learning to take care of a pet,” he says.

Léo Ramos Chaves/Revista Pesquisa FAPESPThe app is based on a pain scale developed by the UNESP group in 2013Léo Ramos Chaves/Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Dogs are italian, cats are japanese

The VetPain app helps users assess pain both in pets (dogs and cats) as well as in livestock (cattle, pigs, sheep, donkeys, and horses) and laboratory animals (rabbits, mice, and rats). Each species has its own pain scale. According to Luna, when experiencing pain, certain behaviors are common across species, such as loss of appetite, arched posture, or a drooping head. Others are more species-specific. “For example, cats stretch their legs when they feel pain,” he explains. The differences between species mean they each have peculiar ways to express suffering. “I often joke that dogs, like Italians, are more communicative, while cats are like the Japanese, expressing pain in a more subtle manner.”

Due to their discreet nature, feline suffering often draws less attention than canine suffering. “In veterinary consultations, professionals tend to attribute more pain to dogs than to cats,” the researcher says. This was the primary reason for choosing cats as the first species to be featured in the app.

The program is based on a pain scale developed and validated by Luna’s research group in 2013. It was one of the earliest pain scales for cats and has since become a globally recognized reference. In 2022, his team released a condensed version of this scale. Both scales are available in the app. They then developed and validated scales for cattle (2014), horses (2015), sheep and pigs (2020), donkeys (2021), and rabbits (2022), as well as chronic pain scales for dogs (2019 and 2022). With the exception of dogs, they assessed both postoperative acute pain as well as chronic pain resulting from conditions such as osteoarthritis.

“There were already acute pain scales available for dogs back then. Now we are developing our own scale,” explains Luna. Their research findings have been endorsed by animal ethics committees at over 20 partner institutions in Brazil and in countries across the Americas, Europe, and Asia.

Several researchers who were supervised by Luna during their doctoral studies and are now faculty members at higher education institutions in Brazil and abroad also participated in the studies. One of them, veterinarian Paulo Steagall, now a professor at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Montreal in Canada, has also developed a pain scale and a dedicated app for cats in his laboratory. His Feline Grimace Scale app helps users evaluate acute pain in cats by analyzing changes in their facial expressions. It is available for download on mobile app stores. A paper describing the development and validation of the scale was published in 2019 in Scientific Reports, a Nature group journal.