A landmark in the restoration of democracy and in the recognition of social and civil rights, the Brazilian Constitution achieved its 30-year anniversary in October. It comes amid an intensifying debate about its capacity to sustain the socio-political pact that has since governed the country’s democracy and its institutions. Not only the anniversary, but also the crisis that Brazil has experienced over the last several years has demanded deeper reflection from researchers on the subject. Studies on the constituent process, constitutionalization and its effects on social policies, the prominence of the Judiciary, as well as analyses on the future of the constitution have become increasingly relevant in scientific production, especially in the areas of law, political science, and economics.

Throughout these three decades one of the major academic challenges has been to understand how the constitutional process, whose origins would suggest an important influence from conservative factions (many of which were involved in the military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985), resulted in a document aimed toward social rights. A fundamental key to understanding this issue lies in analyzing the interactions between the political forces involved and the set of rules that guided the debates and the drafting of the Constitution itself—the National Constituent Assembly’s (ANC) internal bylaws.

In 1986, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) won a significant vote, obtaining 54% of the seats, or 303 of the 559 seats being contested in the elections to the ANC. Together with the Liberal Front Party (PFL) formed by dissidents from the National Renewal Alliance (ARENA, the party in support of the dictatorship), the PMDB formed part of the Democratic Alliance, a very heterogeneous but predominantly conservative coalition. The Democratic Alliance included politicians linked to the military as well as congressmen aligned with what was considered a more progressive agenda, as was the case with Mário Covas. When he assumed leadership of the PMDB in the Constituent Assembly, the São Paulo senator led the party to break with the Democratic Alliance. “From then on, the constituency became polarized, with a progressive bloc on one side formed by the Mário Covas-led PMDB, together with parties such as the PT [Worker’s Party] and the Democratic Labor Party (PDT), depending on the agenda. On the other side were the forces that supported the regime, including the PFL and PTB [Brazilian Labor Party],” says political scientist Antônio Sérgio Rocha, from the Department of Social Sciences of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Guarulhos campus.

Arquivo Agência Brasil

The president of the ANC, Ulysses Guimarães (1916–1992), formally enacts the constitution: “I declare this document of freedom, democracy, and social justice for Brazil ratified!”Arquivo Agência BrasilMore organized and cohesive, the so-called progressives managed to include rules in the bylaws, for example, which allowed for the decentralization of the constituent process. Thematic committees and subcommittees had the power to initiate and establish the agenda of debates and were responsible for formatting the draft projects that would only later be voted on in the plenary session. “With his political ability, the PMDB leader [Mário Covas] was able to assign to most of the committees chairpersons who were committed to the social agenda. This assured an advantage for progressives, who were a minority in the ANC,” says political scientist Lucas Costa. A researcher at the Center for Public Sector Policy and Economics (CEPESP) of the Getulio Vargas Foundation School of Business Administration (EAESP-FGV), Costa studies the influence of the Brazilian Constitution on other Latin American constitutions, especially with regard to the implementation of social policies.

Direct Democracy

Another singular aspect of the constituent process was the introduction of mechanisms for direct democracy. “Until then, it was very rare to have a constituent process that included tools for popular participation such as occurred in the case of Brazil, with popular amendments and public hearings,” Costa observes. The provision that regulated the popular amendments guaranteed that any proposal submitted with the signatures of at least 30,000 Brazilian voters and the recognition of at least three political associations would be discussed and voted on in the Constituent Assembly.

In Costa’s view, the fact that most of the subcommittees were chaired by progressives and that the bylaws allowed for ample popular participation ensured the advancement of the social agenda during the ANC’s initial moments. At that stage, there was active participation from various interest groups. “For example, DIAP [the Inter-Union Department of Parliamentary Counsel], was able to unite trade unions such as CUT [Unified Workers’ Central] and the CGT [General Workers’ Central] in defense of its agenda, while business stakeholders acted individually and with little cohesion,” he adds. In addition to mobilizing labor, groups that defended health and education agendas also organized around their issues.

Senado fotos

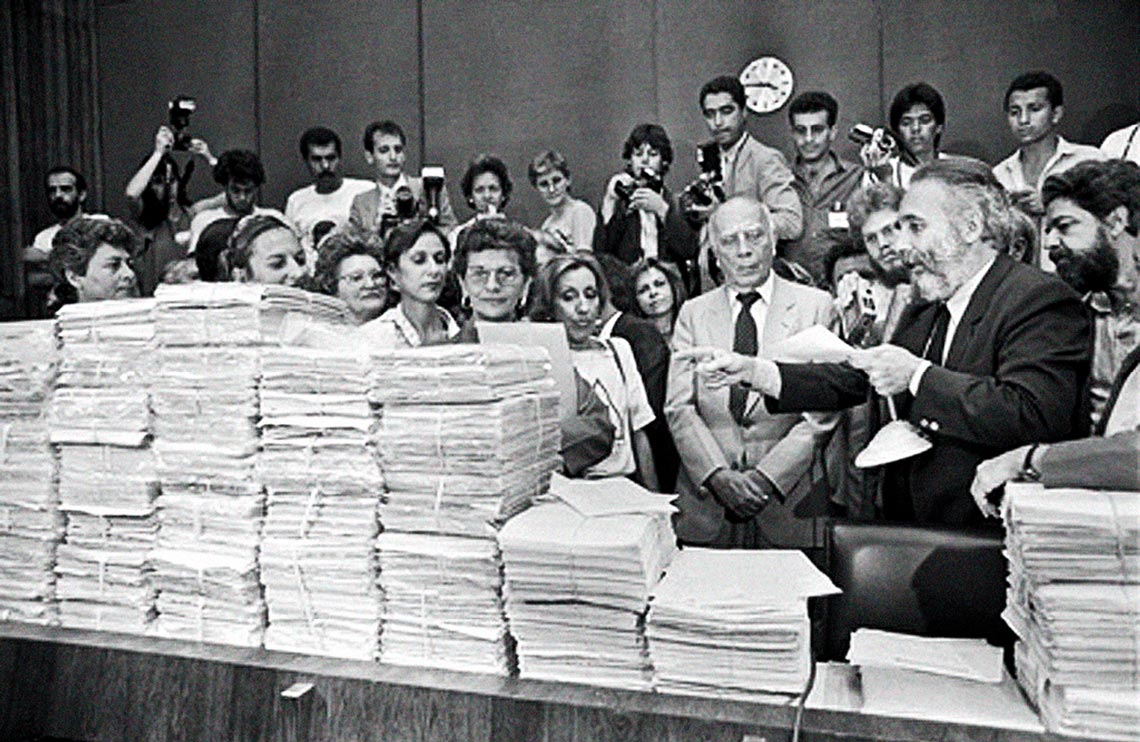

Urbanist and Catholic leader Francisco Whitaker (right) delivers a set of popular amendments, proposed by millions of citizens, to the president of the ANCSenado fotosAt the same time, social movements fighting for popular participation in the Constituent Assembly found an important ally in the progressive wing of the Catholic Church. The extensiveness of this protagonism is one of the revelations of the research project A Constituinte recuperada: Vozes da transição, memória da redemocratização, 1983–1988 [The Constituent restored: Voices of transition, memories of reinstating democracy, 1983–1988]. More than one hundred of those involved in the political transition, and in the work of the National Constituent Assembly, were interviewed in an effort coordinated by UNIFESP’s Antônio Sérgio.

He recalls that beginning in the late 1970s, under an initiative of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops (CNBB), a group of legal experts traveled around the country, taking advantage of the basic ecclesial communities’ structure and connection to the church, and explaining to people the importance of a new Constituent Assembly that would restore the democratic state of law. “Mobilizing the Catholic Church was instrumental in the drive to collect signatures for popular amendments in some of the country’s most diverse locations. In addition, according to urban planner and Catholic leader Francisco Whitaker, the church also helped charter buses to ensure access by social movements to the public hearings in Brasília, and hosted the groups’ leaders at convents and ecclesiastical buildings in the capital,” reports Antônio Sérgio.

The conservative forces

For the next phase of the work, each thematic committee presented its preliminary draft to the Systematization Committee, which was responsible for integrating the various demands. This process resulted in the first draft of the Constitution, which, as observed in the studies of both Antônio Sérgio and Costa, reflected the overrepresentation of the progressive wing within the thematic committees. The next stage would have been a vote in plenary, but the rules of the internal bylaws imposed limitations on changing the text. Unhappy with the course of the proceedings, the more conservative sectors of the ANC tried to regain control. Under the command of then President of the Republic José Sarney (1985–1990), a cross-party coalition was formed that would become known as the Centrão [literally, the large center]. Their principal objective was to amend the bylaws to allow for the submission of amendments and substitutions in plenary and to modify the draft approved by the Systematization Committee. The bloc also acted to overthrow two specific measures: the parliamentary system of government and a four-year term for Sarney, as their coalition advocated for a presidential system and a five-year mandate. The cross-party coalition was successful, and new internal bylaws more conducive to modifications in plenary were approved.

Lula Marques / Folhapress

Senator Mário Covas heads the “Consensus Group,” in July 1987, during the drafting of the ConstitutionLula Marques / FolhapressIn addition to maintaining the powers of the Executive, this same bloc also defended measures proposed by the military leadership. According to Antônio Sérgio’s research, the then minister of the army, General Leônidas Pires Gonçalves (1921–2015), drafted a document with 26 demands from the military. One of these demands stipulated that the Armed Forces would be responsible for ensuring law and order within the national territory. Attenuated in its final wording, this demand was reflected in Article 142 of the Constitution, which specified that the Armed Forces shall be subordinated to the Presidency of the Republic, and “are intended for the defense of the Country, for the guarantee of the constitutional powers, and, on the initiative of any of these, of law and order.”

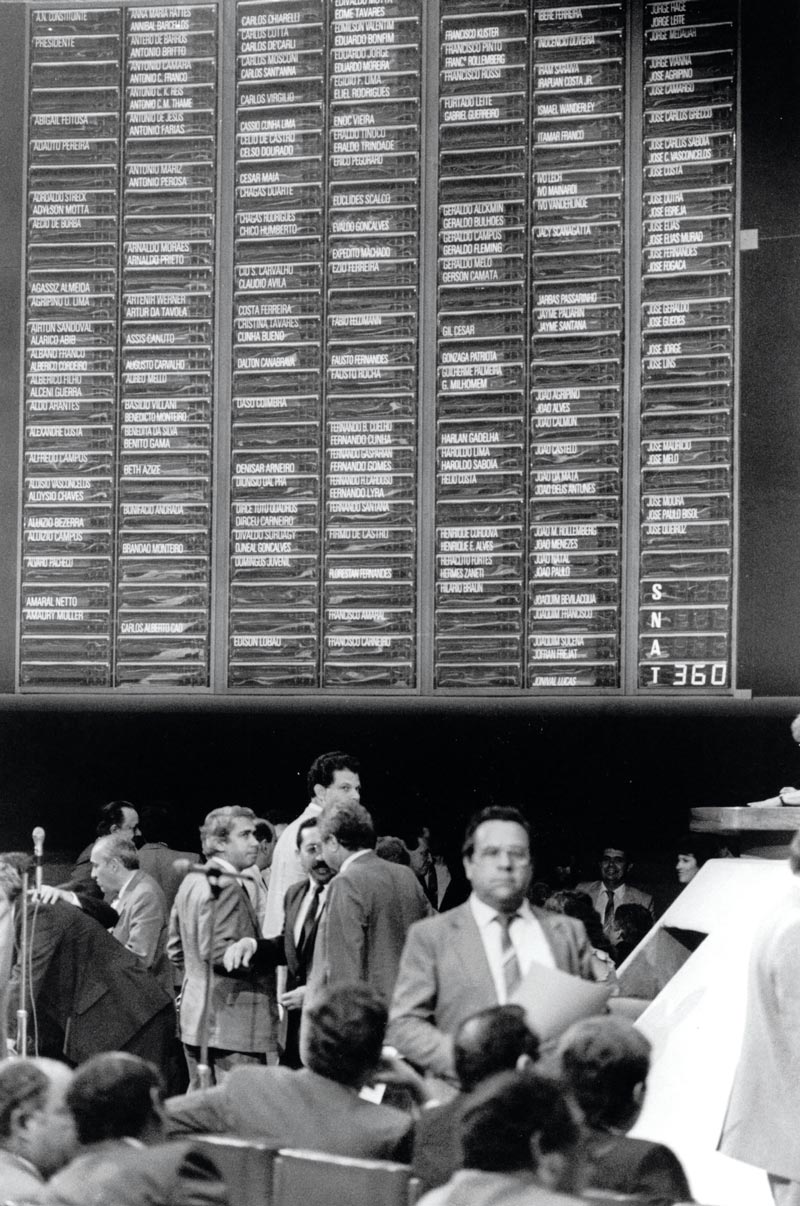

Changes in the internal bylaws and the interaction between political forces delayed the process. Begun on February 1, 1987, and scheduled to close on November 15 of that year, the Brazilian Constituent Assembly actually lasted 20 months, a period that was quite long compared to other recent Latin American constitutional proceedings. In Bolivia’s case, which is closest to Brazil’s in terms of duration, the assembly lasted 16 months; in Venezuela and Colombia, four months. The final text of the Constitution was approved in plenary on September 22, 1988, with 474 votes in favor, 15 against, and 6 abstentions. Although 15 of the 16 constituents of the PT had voted against the final draft, believing that even though there had been improvements the prevailing power structures would remain intact, the party did sign the final document.

Even with the changes in the internal bylaws and meeting several of the conservatives’ demands, the final text didn’t lose its fundamentally progressive characteristics. In Costa’s view, this is because the political cost of withdrawing most of the rights included in the initial stages of the constituent process would have been too high. In this manner, even though some concessions were made, the progressives succeeded in getting a document ratified that included many of their proposals.

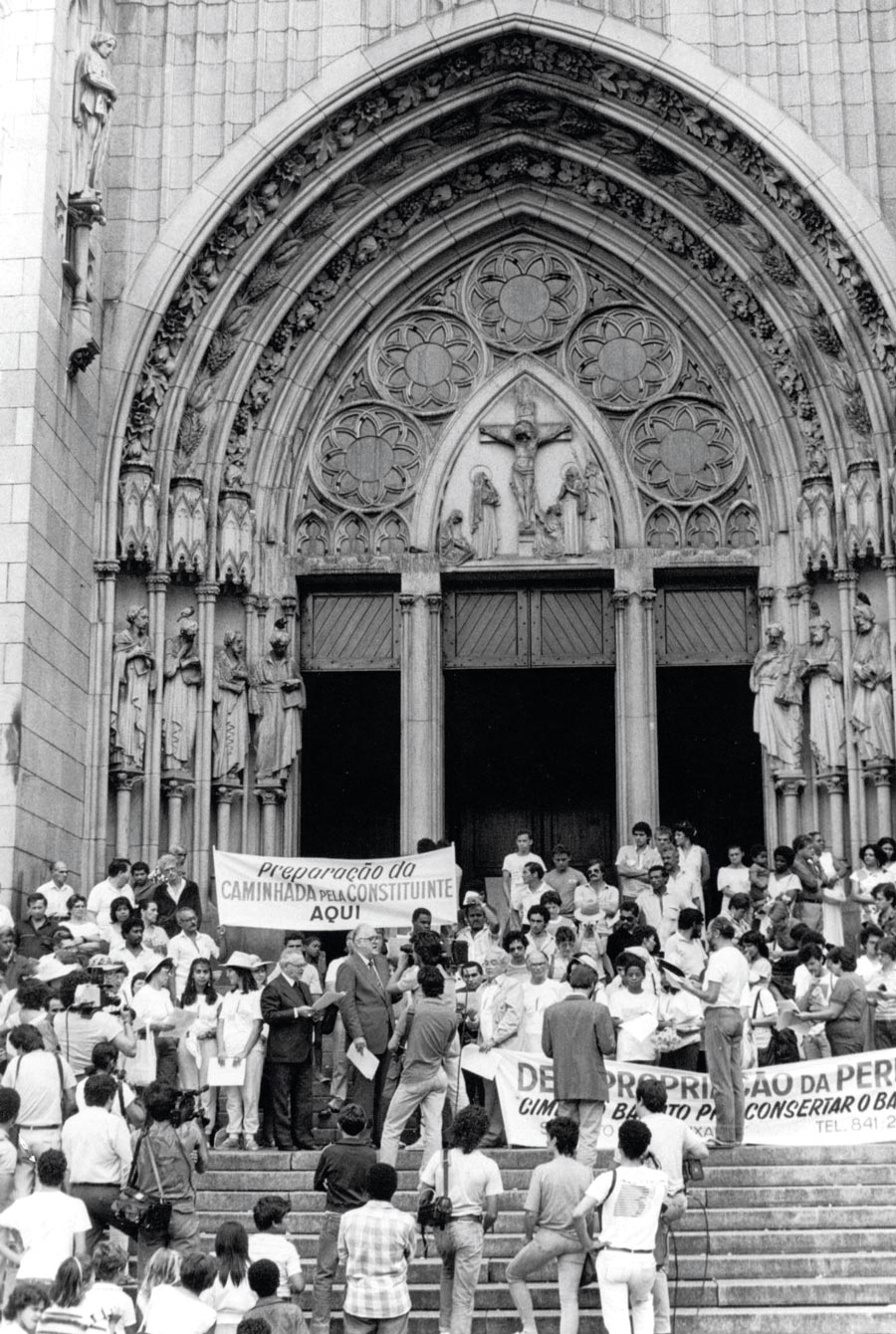

Fernando Santos / Folhapress

In front of the Sé Cathedral, in São Paulo, Dom Paulo Evaristo Arns initiates the Walk for the Constituent Assembly, bound for Brasília in March 1987Fernando Santos / FolhapressSocial policies

Among its main provisions, the Constitution of 1988 establishes the state as the guarantor of policies aimed at universalizing education and healthcare, reestablishes individual liberties and freedom of expression, innovates in the chapter on environmental issues, and consolidates labor rights. It also promotes the rights of minority populations such as quilombolas [former slaves and their descendants with occupied lands] and indigenous peoples. As the result of an association between anthropologists, legal experts, and indigenous leaders, the Constitution is the first in the country’s history to devote an entire chapter to indigenous peoples. The document confers on the state the duty of maintaining protective relations with traditional communities and promoting their rights. “It’s a milestone because it introduces the idea that these peoples have the right to a future and to continue to exist,” summarizes Samuel Barbosa, a professor at the University of São Paulo Law School (USP). He is the organizer, with anthropologist Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, of the recently launched Direitos dos povos indígenas em disputa (Indigenous Peoples Rights in Dispute; Editora UNESP). “Until then, the view of native peoples was that they were relics of the past that would disappear as they were assimilated into the national culture.”

Another important paradigm shift was the establishment of “original rights,” the assurance that natives are entitled to traditionally occupied lands. “This is different from moving people to an indigenous reserve, which is an artificial creation of the state,” Barbosa explains. In the Constitution, the original lands are the property of the federal government, whose responsibility is to demarcate them and guarantee their ownership to the natives. “The demarcation is a necessary condition for the natives’ physical and cultural reproduction because, for them, the land has not only economic but also cultural and religious dimensions. Without that bond with the land, their traditions disappear, and the indigenous peoples are assimilated,” he says.

“The Constitution establishes a paradigm shift for social policies, guaranteeing everyone, for example, the right to retirement and healthcare, benefits which were previously restricted to those who had formal employment,” observes political scientist Marta Arretche, from the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP). Arretche is also coordinator of the Center for Metropolitan Studies (CEM), one of the Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDC) supported by FAPESP. “About 60% of the population, which had previously been excluded, started to make use of these social policies, which is no small thing,” she adds (see article on page 26).