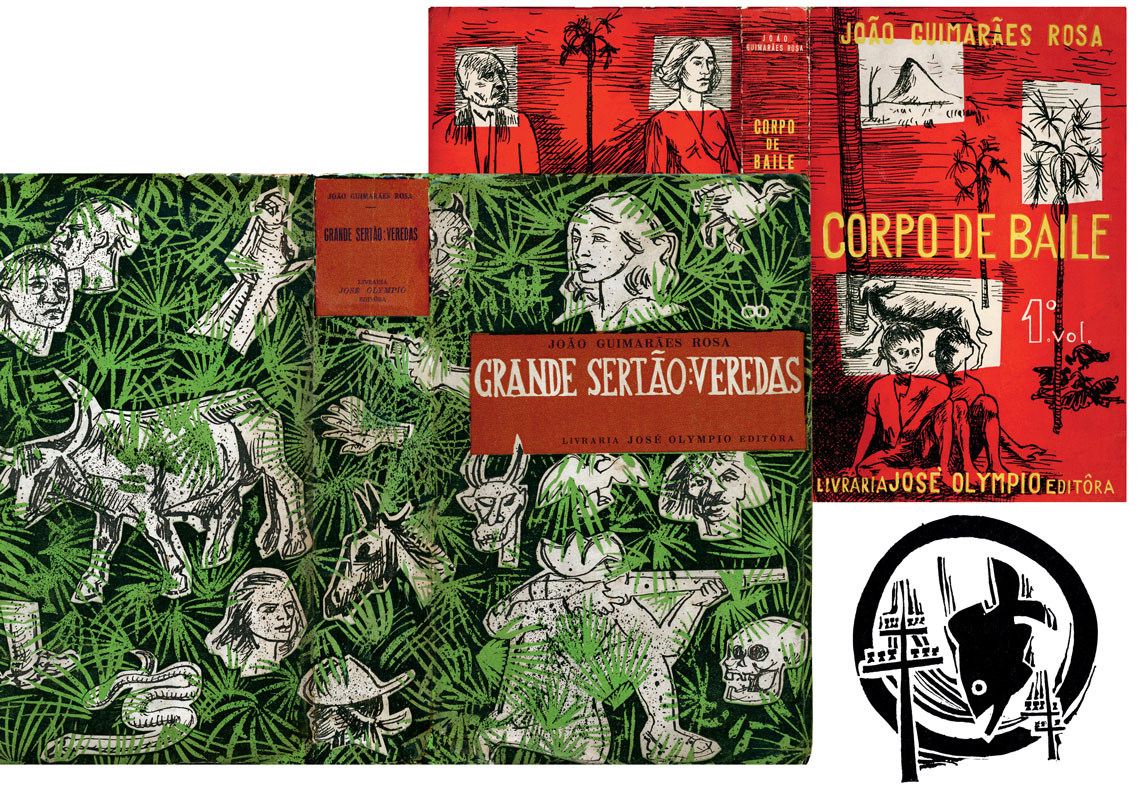

In 1956, as the July release of Grande sertão: Veredas (The Devil to Pay in the Backlands) drew nearer, João Guimarães Rosa (1908–1967) made a point of ensuring that the plot of the novel, published by Livraria José Olympio Editora, remained a tightly kept secret. Apart from the editor, José Olympio Pereira Filho (1902–1990), very few people knew what the story was about. One person who did, however, was Poty Lazzarotto (1924–1998), who was responsible for designing the cover and the maps on the flaps of the dust jacket. During an eight-hour conversation, the writer from Minas Gerais shared the details of the adventures and misadventures Riobaldo and Diadorim with the artist from Paraná (who had not yet read the story), giving him precise instructions on how he wanted the book to be illustrated. “He told me which episodes he found most significant. I had a privileged insight as the custodian of a closely guarded secret: no more than eight people knew about the Diadorim mystery,” Lazzarotto later recalled in an interview with writer and visual artist Valêncio Xavier (1933–2008), author of the book Poty, trilhas e traços (Poty, trails and traces; Curitiba City Hall, 1994).

After lending his style to the fourth edition of Sagarana (1946) and the first edition of Corpo de baile (Corps de ballet; 1956) in the 1950s, both published by José Olympio, Lazzarotto helped establish a visual identity for Rosa’s work. Fabricio Vaz Nunes, a visual artist and professor of art history at the State University of Paraná (UNESPAR), agrees. “Rosa requested very specific drawings from Lazzarotto. In Sagarana, for example, there are some very enigmatic elements, such as a fish ‘raining’ on power lines. With his images, he enriched the symbolic universe of Guimarães Rosa,” says Nunes, who released the book Texto e imagem: A ilustração literária de Poty Lazzarotto (Text and image: Poty Lazzarotto’s literary illustration; Edusp) at the end of last year, based on the doctoral thesis he defended at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) in 2015.

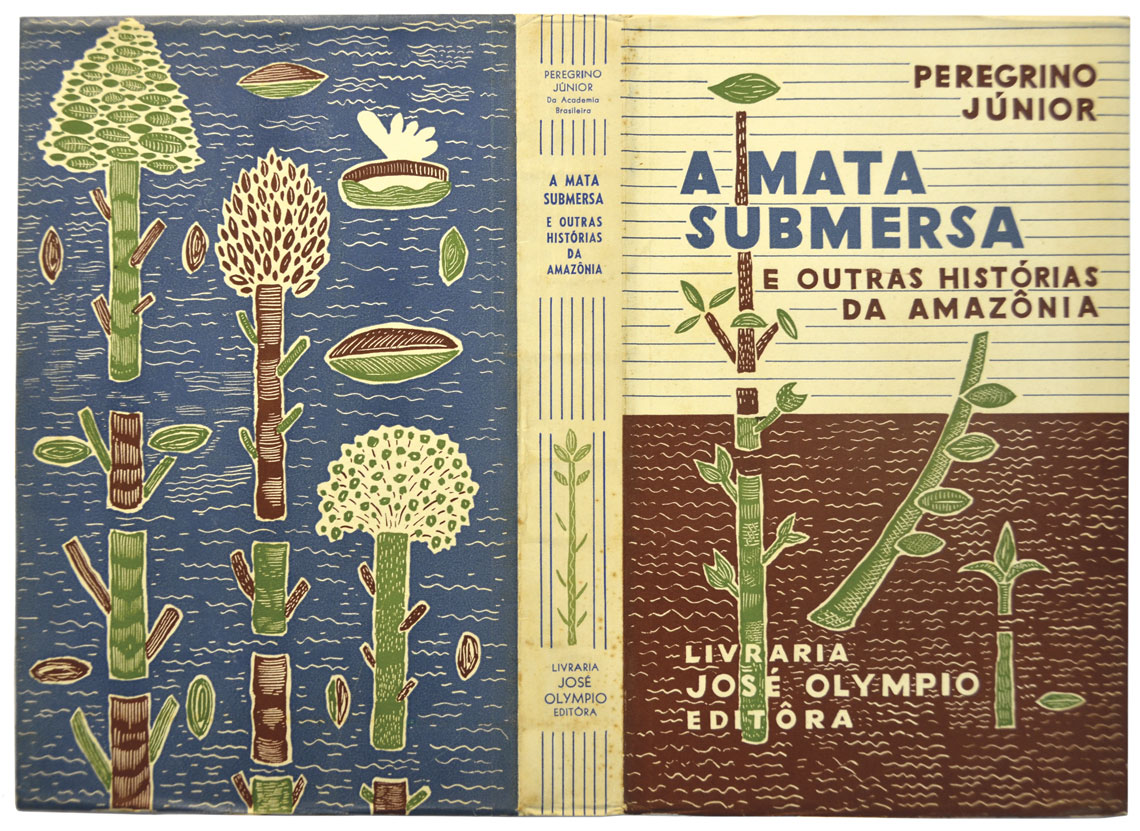

The book, which was named best literature and linguistics thesis by the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) in 2016, seeks to demonstrate how Lazzarotto’s illustrations interact with literary works. One book that features his artwork is a rare deluxe edition of Canudos (Sociedade dos Cem Bibliófilos do Brasil, 1956), a book of letters written in 1897 by Euclides da Cunha (1866–1909) during his coverage of the War of Canudos, in the interior of Bahia, as a correspondent for the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo. “Before starting the illustrations, Lazzarotto traveled to Canudos in 1950 and 1951 to gather information about the region. This is reflected in the way he draws some of the plant species,” says Nunes.

“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla FontanaCovers of “First stories” and “Tutaméia” by Luis Jardim“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana

Born in the city of Curitiba, where he later created countless public murals and displays, Napoleon Potyguara Lazzarotto illustrated more than 170 books for several publishers over five decades, including covers, frontispieces, and drawings interspersed within texts. The artist began his career at the Curitiba literary magazine Joaquim (1946–1948), headed by writer Dalton Trevisan, with whom he maintained a strong partnership. In the late 1940s, he moved to Rio de Janeiro to study at the National School of Fine Arts, where he discovered a supportive environment for modern-leaning illustrators interested in literature. From then on, he created visuals for a range of literary genres and by a variety of authors, from Rio de Janeiro’s own Machado de Assis (1839–1908) to the American writer Herman Melville (1819–1891). In some cases, such as with Sagarana, the illustrator even added elements that were not included in the original work, creating a “complement” to the story. “Literary illustration is a type of interpretation of the text. Lazzarotto was a voracious reader who strived to create a specific style for each author and each book,” explains Nunes.

In 1953, the artist began collaborating with José Olympio. Three years later, having illustrated the Brazilian version of Melville’s novel Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, he became one of the country’s most renowned illustrators. The publishing company, Livraria José Olympio Editora, was founded as a bookstore in São Paulo in 1931 and opened a branch in Rio around three years later, going on to establish itself as one of the most important publishers in the Brazilian book market over the course of the next decade. “In the 1930s, the sector experienced a surge of industrialization in Brazil. In the midst of this boom, Brazilian publishers invested more in illustrated covers and the visual aspect of books,” says Edna Lúcia Cunha Lima, a former professor from the Department of Arts and Design at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio). The use of figurative as well as verbal elements on the covers of books from the period is due, among other factors, to technological advances, according to Priscila Lena Farias, a professor at the School of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (FAU-USP). “Modern machinery for producing stereotypes and printing in multiple colors became more accessible in Brazil at the beginning of the twentieth century,” she explains.

“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla FontanaAbove and right, two covers drawn by Poty for José Olympio in the 1950s. The covers of the 1948 editions of the books by Honoré de Balzac and Rachel de Queiroz were illustrated by Jardim“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana

José Olympio was not alone in this field. “Other publishers, even outside the Rio-São Paulo axis, such as Livraria do Globo in Porto Alegre, also played a major role in graphic design during this period,” Lima adds. In Brazilian literature, however, it was the covers produced by José Olympio for novels of the nascent social and regionalist literature by authors such as Jorge Amado (1912–2001) and Graciliano Ramos (1892–1953) that garnered the most attention. The “colorful covers with a central design in black and white,” made José Olympio “the symbol of renewal incorporated into public taste” in the mid-1930s, in the words of literary critic Antonio Candido (1918–2017).

Behind this famous style was Tomás Santa Rosa (1909–1956) from Paraíba, who among other talents, was a graphic artist, painter, set designer, and art critic. “Today, anyone who looks at a novel from the 1930s can immediately recognize that it was published by José Olympio due to Santa Rosa’s graphic design,” says Luís Bueno, professor of Brazilian literature and literary theory at UFPR. According to Bueno, before settling in Rio de Janeiro in the early 1930s and becoming the publisher’s main illustrator, Santa Rosa was an employee of Banco do Brasil and lived in several cities in the Northeast, including Maceió. That is where he met the writers José Lins do Rego (1901–1957), Graciliano Ramos, and Rachel de Queiroz (1910–2003). It was contacts like these that helped Santa Rosa break into the literary world. One of the first covers designed by Santa Rosa was for the book Urucungo (1932), written by the poet Raul Bopp (1898–1984) and published by Ariel, one of the biggest publishers in Rio at the time. “Santa Rosa became famous in the 1930s, when regionalist novels set the tone in Brazilian literature. He created the covers for all the works by José Lins do Rego and Graciliano Ramos, with the exception of the posthumously published Viagem (Journey) [1954], the cover of which was drawn by Di Cavalcanti [1897–1976],” says Bueno, himself the author of the book Capas de Santa Rosa (Santa Rosa covers; Senac/Ateliê, 2016).

“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana | Capas de Santa Rosa (Senac / Ateliê, 2016)Two covers by Santa Rosa in the style he created for a series of books published by José Olympio in the 1930s. On the bottom row, two books from French publisher Librairie Stock that inspired Santa Rosa“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana | Capas de Santa Rosa (Senac / Ateliê, 2016)

While the visual style Santa Rosa established for José Olympio became known as the “face” of Brazilian literature of the period, the illustrator did not seek aesthetic inspiration for his work in Brazilian regionalism, according to editor Carla Fontana’s doctoral thesis “Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (Patterns and variations: Graphic arts at Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962)”, supervised by Farias and defended at FAU-USP in 2021. In her research, she discovered that in terms of composition, color scheme, and positioning of elements, Santa Rosa’s paradigmatic covers shared many similarities with a French publishing house. “What is now considered a hallmark of Brazilian graphic design was actually copied from a collection published by Librairie Stock in Paris. This was a very common approach at José Olympio. The professionals there were inspired by foreign ideas,” says Fontana, who studied documents from the publisher’s archive that are now stored at Brazil’s National Library in Rio de Janeiro. “In his articles, Santa Rosa defended a more classic and restrained style. He believed that covers should be more discreet, with a readable title, a centered layout, and a small illustration or vignette. Contrary to what many people think, Santa Rosa was not visually innovative at José Olympio,” she says.

In her thesis, Fontana described the career and work of Lazzarotto and Santa Rosa, as well as three other graphic artists who frequently collaborated with José Olympio but never obtained the same level of recognition. One was Luis Jardim (1901–1987), a writer from Pernambuco who published children’s books, plays, stories, and novels, some of them with his own illustrations. He also designed the covers for other authors, including Primeiras estórias (First stories; 1962) and Tutaméia (1968) by Guimarães Rosa. “He was best known as a writer, but he had the longest relationship with José Olympio of any graphic artist, working with the publisher from the 1930s until the 1970s. In 1957, he was made a permanent employee, taking on a position in the editorial department,” says the researcher. “Over the course of five decades he drew more than 300 covers, in addition to creating illustrations and vignettes for around 50 books. While Santa Rosa tended to emphasize scenes or characters, Luis Jardim generally portrayed places and landscapes.”

“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana A book cover designed by Jardim (1960)“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana

The other two graphic artists studied by Fontana were Raul Brito and George Bloow. The former created around 50 covers for José Olympio in the 1940s, mainly for translated foreign collections, such as A ciência de hoje (The science of today) and A ciência da vida (The science of life). He also worked as a poster artist at the Brazilian office of the American film company Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. “Many graphic artists at José Olympio were also poster artists. Santa Rosa himself produced the launch poster for the book Capitães de areia [Sand Captains; Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1937], by Jorge Amado,” says Farias, from FAU-USP.

Bloow came to Brazil from France in the 1910s as part of a variety show troupe and ended up settling in the country. He designed posters, diplomas, and stamps for sporting events, commissioned by institutions such as the Brazilian Rowing Federation. At José Olympio, he produced around 50 cover layouts between 1948 and his death in 1956. “One of his specialties at the publishing house was the production of binding ornaments. At that time, José Olympio was investing in bound book sets to sell in installments, for which it wanted to portray an image of a ‘luxury’ product,” says Fontana. She adds: “José Olympio’s fame is largely due to its recognizable covers by Santa Rosa, but this obviously does not reflect the publisher’s entire catalog. In my thesis, I tried to show that there were patterns and variations in the visual aspect of the publications”.

“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana Drawings and a printed cover by Raul Brito for a book published by José Olympio in 1941“Padrões e variações: Artes gráficas na Livraria José Olympio Editora, 1932–1962” (FAU-USP, 2021). Reproductions: Carla Fontana

According to Fontana, of these five graphic artists who worked with José Olympio, Lazzarotto has received the most attention from researchers in recent years. In the CAPES catalog of theses and dissertations, there are 10 master’s dissertations and three PhD theses about the writer defended between the 2000s and 2020s. On the centenary of his birth, three exhibitions dedicated to him are currently on display in his hometown: Trilhos e traços (Trails and traces) at the Oscar Niemeyer Museum, Poty expandido (Expanded Poty) at Caixa Cultural, and Poty de Curitiba, Curitiba de Poty (Curitiba’s Poty, Poty’s Curitiba) at the Municipal Museum of Art. “Because of his murals depicting historical themes of Paraná, Poty was named the state’s official artist. But his legacy is much greater than that,” says Nunes. “Through images, he spoke to authors from Brazil and around the world.”

Republish