EDMOND SERGENT, LA LUTTE CONTRE LES MOUSTIQUES: UNE CAMPAGNE ANTIPALUDIQUE EN ALGÉRIE, 1903A longstanding struggle: health care workers protect themselves with a tulle veil and throw oil on ponds to avoid the AnophelesEDMOND SERGENT, LA LUTTE CONTRE LES MOUSTIQUES: UNE CAMPAGNE ANTIPALUDIQUE EN ALGÉRIE, 1903

People who visit the Amazon Region fear returning with malaria. As there is no vaccine, one way to protect oneself is to take drugs that avoid the damage inflicted by the protozoans that cause the disease. The side effects of the preventive medication, however, can be serious – including enhanced sensitivity to light and sunburn. Whether to use or to avoid preventive medication so that the benefits outdo the inconveniences depends on variables such as where the traveler is going to, how long he is staying there, the time of year he will travel and how near the medical care centers will be, according to recent work by a group of researchers from the School of Medicine at the University of São Paulo (USP), which has outlined the risks of getting malaria in Brazil, in Africa and in three Asian countries (Thailand, Indonesia and India). Worldwide, every year, malaria is diagnosed for the first time in 200 million people, of whom 100 million live in Africa. Of these 100 million, 1 million are children. In Brazil, some 300 thousand people have malaria a year, far less than the 6 million cases a year in the early 1940’s.

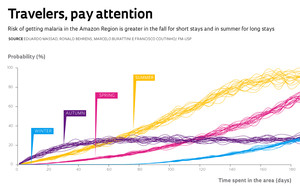

The risk of being bitten by mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus, which transmit malaria, is minimum in the Amazon Region’s winter, i.e., the rainy season, from December to February. It grows in autumn and peaks during the region’s summer, which is the dry season, the height of which runs from July to August. “Summer is the worst time because the transmitting mosquitoes are at the peak of their activity,” says Eduardo Massad, one of the coordinators of the research group that outlined the risks of contagion taking into account not only the climate, but also the speed at which the Anopheles can reproduce, become infected, or infect people. In a study published in Malaria Journal in 2009, Massad, Marcelo Buratini and Francisco Antonio Bezerra Coutinho, from USP , and Ronald Behrens, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Diseases, state that the risk for a traveler in the Amazon region of contracting malaria is at least 10 times higher in summer than in the winter.

The destination and the time spent in the area also matter. “Anyone that’s going for three days to a resort on the Negro river, an area of dark water with almost no malaria, doesn’t need to take any prophylactic medication,” says the physician Jessé Reis Alves, from the Emílio Ribas Infectology Institute. “Depending on the objective and the circumstances of the trip, the risk may vary even in the same place,” notes the infectologist physician Marcos Boulos, a professor at the USP School of Medicine. “A backpacker planning on camping out in the open is far more at risk of getting malaria than someone staying in a five-star hotel.”

The preventive measures start by becoming aware of the risk of contracting the disease in the region that one is visiting. “Many people travel to areas with a high malaria risk without knowing it,” says Alves. It is important also to be aware of the early symptoms – fever, body pains, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, dizziness and tiredness. The treatment is simple and effective, provided that the right diagnosis is made as soon as the first symptoms appear, thus avoiding the liver, lungs and brain damage that go with the more severe cases.

It is also useful to be aware of the basic habits of the Anopheles darlingi, the mosquito that transmits malaria in Brazil. It leaves its hiding places at nightfall and dawn to feed. However, this is not always the case for all mosquitoes. In Africa, the Anopheles gambiae, another transmitter, also attacks in daytime. More differences: in Brazil, not all the A. darlingi are infected with the agent that causes the illness, which here is normally the Plasmodium vivax, responsible for a less severe form of the disease. In Brazil, malaria is essentially rural and rarely appears in cities. Finally, there is a healthcare network with some three thousand diagnosis and treatment points in the Amazon Region. In Africa, the A. gambiae has a high level of infestation (hence a greater risk of transmission), generally with Plasmodium falciparum, which causes a more severe and sometimes fatal form of malaria. There, the disease arises in both rural and urban environments and the healthcare clinics are rare.

It is also useful to be aware of the basic habits of the Anopheles darlingi, the mosquito that transmits malaria in Brazil. It leaves its hiding places at nightfall and dawn to feed. However, this is not always the case for all mosquitoes. In Africa, the Anopheles gambiae, another transmitter, also attacks in daytime. More differences: in Brazil, not all the A. darlingi are infected with the agent that causes the illness, which here is normally the Plasmodium vivax, responsible for a less severe form of the disease. In Brazil, malaria is essentially rural and rarely appears in cities. Finally, there is a healthcare network with some three thousand diagnosis and treatment points in the Amazon Region. In Africa, the A. gambiae has a high level of infestation (hence a greater risk of transmission), generally with Plasmodium falciparum, which causes a more severe and sometimes fatal form of malaria. There, the disease arises in both rural and urban environments and the healthcare clinics are rare.

Another preventive measure is to use skin repellants and wear long-sleeved shirts and long trousers, especially during the times and places where the mosquitoes are more frequent, since the risk of getting malaria increases with the number of bites of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes. Physicians recommend that travelers, when they find themselves in places where malaria is common, put mosquito nets or screens over their hammocks or beds before sleeping, preferably in enclosed places. “The risk of catching malaria drops by as much as 80% when one protects oneself against mosquito bites properly,” says Alves. Alternatively, those who do not want to start the medication before the trip can take the antimalaria drugs along when they visit a high risk area and start taking them if they get a fever, even without doing a blood test to confirm the disease.

Physicians say that medication should complement the preventive measures rather than being used on its own, because of its unpleasant side effects. Besides increasing sensitivity to sunlight, chloroquine, the antimalarial drug used most often in Brazil at present, may cause nausea. Mefloquine, though efficient, has stopped being used officially because it can increase the risk of psychiatric disturbances and suicidal tendencies. Boulos tells the story of a German executive who worked in the town of São Bernardo do Campo, in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area, who took chloroquine for three years preventively, even though it was unnecessary; he did not get malaria, but went blind from too much medication. Another inconvenient aspect is that, to work properly, treatment with these drugs should be started one to two weeks before arriving in the risk area, and then kept up while the traveler is there and for four weeks after returning home. A two-week trip, therefore, implies taking medication for nine weeks.

Additionally, the antimalarial drugs work better against Plasmodium falciparum, less common in Brazil, than against P. vivax. Last, there is also the possibility that the Plasmodium – especially the falciparum kind – might become resistant to the drugs. In this case, a careful traveler who took the antimalarial drug might get a fever and extreme tiredness, both of them typical malaria symptoms, but think that they are unrelated to the disease, when actually it is the medication that is not fighting drug-resistant Plasmodium.

In November of 2010, two travelers – one from Nigeria and another from the Ivory Coast – died of malaria in São Paulo after going to several hospitals, whose doctors failed to identify the disease. “When returning home, in the event of a high fever, the traveler should tell the physician about the trip and insist on having a malaria test done,” Alves emphasizes. Sometimes, it does not occur to doctors that fever and malaise are malaria symptoms, as they have probably never diagnosed the disease.

“The responsibility for prevention belongs to the healthcare service, to the travelers themselves and to companies that send employees to high-risk areas,” says Alves. According to him, whoever is going to work in an African country, such as Angola, where malaria is endemic, should take all possible precautionary measures.

Emílio Ribas Health Museum / Reproduction Eduardo Cesar1953 poster: brazilian campaignEmílio Ribas Health Museum / Reproduction Eduardo Cesar

“A two week stay in Africa already justifies preventive measures, including medication,” says Massad. A physics graduate who is also a physician, he headed a study that compared the risk of contracting malaria in Africa, in Brazil and in three Asian countries – Thailand, Indonesia and India. Africa emerged as a high-risk area; Brazil (even in the Amazon region) was ranked as medium-risk, in theory making medication unnecessary for brief visits, since statistically two malaria cases arise for every one thousand trips to the north of Brazil; and the three other countries were considered low-risk areas.

In a study accepted for publication in Malaria Journal, Massad, Behrens and Coutinho analyze the costs and benefits of undertaking preventive measures against malaria on a broad scale for those who travel to countries or regions where the disease is common. The conclusion may sound odd, but Massad reminds us that a cost analysis is cold. “From the public health standpoint,” he says, “it’s cheaper to treat those who do get malaria than to keep all travelers from getting the disease.”

The Brazilian approach is to avoid using medication, unless something really justifies it. “I have been doing field work in the Amazon Region since 1974, I have never taken any prophylactic drugs and have never caught malaria,” states Boulos. “The most important thing is to be aware of the risk.” However, Alves and the other physicians at the travelers’ ambulatory clinic at the Emilio Ribas hospital are sometimes unable to explain quickly to a foreign tourist that he does not need to worry about malaria just because he is going to Rio de Janeiro.

A debate in Miami

Errors of this type are common. A map in the book CDC health information for international travel, recently published by the University of Oxford, indicates that all of South America is a high-risk area for malaria, when, in fact, the disease is limited to certain parts of the Amazon Region. “Normally, Europeans understand quickly that the risk is different, even in the Amazon Region, but the Americans refuse to give up their preventive medication,” says Alves.

At an infectology congress held in March of 2010 in Miami, in the United States, Boulos took part in a round-table discussion on preventing malaria with drugs and argued that repellents and other measures should be prioritized. Next to him sat Paul Arguin, from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, advocating the official position of US doctors, who fear that travelers might return with malaria and die or spread the disease because they were not diagnosed correctly. “There’s no reason to use anti-malaria medication in places where there’s no malaria,” Boulos argues. “The risk of getting malaria in São Paulo is the same as in New York.” The debate ended with none of the parties changing their views.

Viruses and bacteria may propagate quickly, especially among people who have never had any contact with these microorganisms. Just a few months ago, two people in São Paulo and one in Rio de Janeiro were diagnosed with the virus chikungunya, common in many African and Asian countries and transmitted by the Aedes, the same mosquito that carries dengue fever. “New diseases can appear and spread fast, because people have never had contact with the agents that cause them and haven’t developed any defenses against them,” Boulos says. Therefore, he foresees “a major epidemic” of type 4 dengue next summer, mainly in the cities, where other types of the dengue virus have already contaminated people.

“From the theoretical point of view, killing the transmitting mosquitoes, principally during outbreaks, is the most efficient way of deterring dengue,” says Massad. “The public campaigns emphasize the destruction of mosquito breeding grounds in still waters, but this way the government excuses itself from the responsibility of killing mosquitoes.” In his opinion, the dengue control policy should combine all strategies.

Scientific articles

MASSAD, E. et al. Modeling the risk of malaria for travelers to areas with stable malaria transmission. Malaria Journal. v. 8, n. 296. 2009.

MASSAD, E. et al. Cost risk benefit analysis to support chemoprophylaxis policy for travelers to malaria endemic countries. Malaria Journal. v. 10, n. 130. 2011.