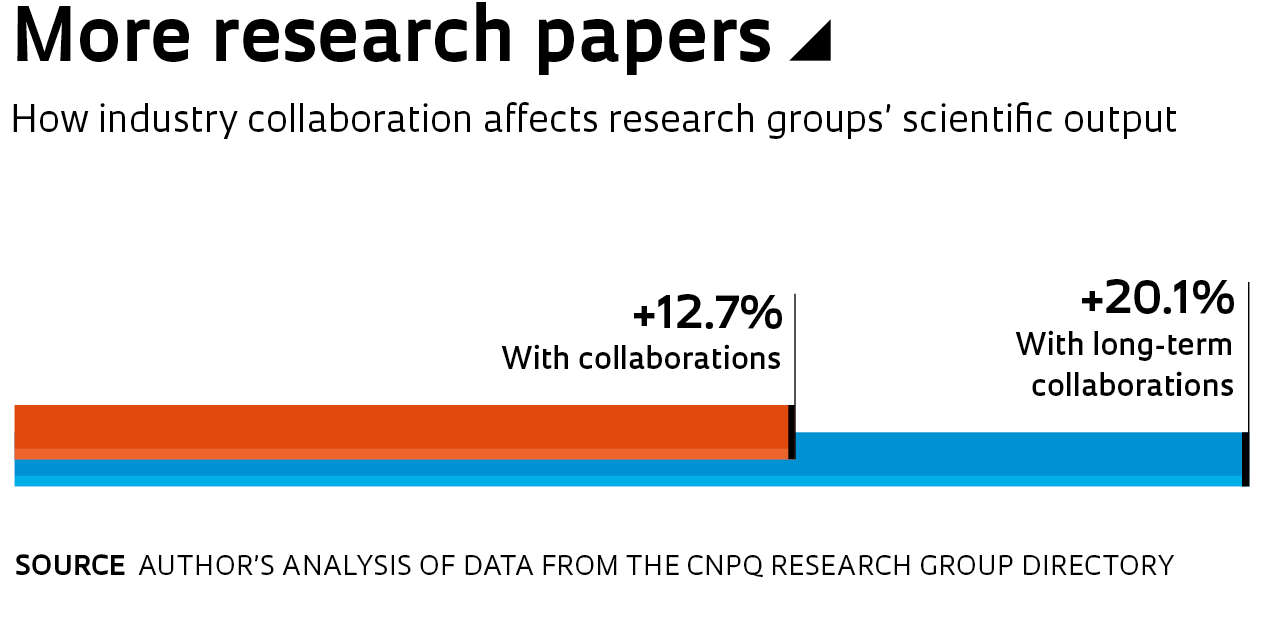

University research groups that collaborate with corporations on innovation projects have 12.7% higher scientific productivity than non-collaborating groups, and when collaborations are long-term, the number of papers they publish is as much as 20.1% greater. These were the findings from a study led by economist Renato Garcia, a professor at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), published in June in Innovation: Organization & Management. The study analyzed research output data for the period 2002–2008 as measured by the Research Group Directory Census, an inventory of active research teams and their performance compiled by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). The article looked at the performance of a total of 7,572 research groups, of which 857 had collaborated with corporations at least once during the study period, and 324 on a permanent basis.

While the data shows a significant correlation between industry collaboration and higher scientific productivity, they are insufficient to demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between collaboration and research output, says Garcia. “These groups are world-class and highly productive, and this attracts corporations seeking partners to solve problems,” he says. Universities are often first approached by alumni who previously studied under research scientists and have gone on to work at research and development (R&D) departments in industry. “But there is also evidence that knowledge generated through industry collaboration can help to broaden researchers’ horizons and lead to more published papers,” he explains.

The study is part of a broader research effort across multiple countries to assess the positive and negative effects of university collaboration with industry, a trend that is growing worldwide as innovation becomes more complex and increasingly requires the active participation of research institutions to produce economically impactful results.

Economist Eduardo Albuquerque, a professor at the Center for Development and Regional Planning at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (CEDEPLAR/UFMG) and an expert on emerging innovation networks, says the article confirms research findings in other countries that show a convergence between academia and industry in producing scientific knowledge. One of the new findings from the current study, he says, is that science output benefits most from larger-scale collaborations. “The paper shows that long-standing and systematic cooperation is more productive for research groups than one-off collaborations,” says Albuquerque, who was not involved in the study. “The results from the study also indicate that university-industry collaboration in Brazil is now more widespread than previously thought, and has recently been intensified.”

The growing interest in long-term partnerships is for good reason: whereas short-term collaborations typically result in only incremental product development, long-term cooperation enables researchers to gain in-depth insight into the wider needs of partner corporations. But there are often concerns that scientists who devote time to multiple, long-term collaborations with industry are neglecting their mission of training students and doing basic research. “There is currently a debate in Brazil, which has been ongoing in other countries, about the extent to which excessive researcher involvement in industry collaborations can undermine academic and scientific activities,” explains Renato Garcia.

The scientific literature on the subject suggests that collaborations with corporations can in some cases undermine academic performance. A group led by economist Albert Bañal-Estañol, of Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, published a paper in Research Policy in 2013 showing that in engineering departments at 40 major universities in the UK, those researchers who had no links to industry published less than those with moderate levels of collaboration, but that very high levels of interaction negatively affected research output. Another paper, published in 2008 in Scientometrics by Colombian engineer Liney Manjarrés-Henríquez, of Universidad de la Costa, in Barranquilla, found that researchers who collaborated with corporations were able to secure more public funding, but their scientific output only improved when that collaboration involved R&D contracts and industry-derived funding did not exceed 15% of the research group’s total budget.

And while the data available from the Research Group Directory at CNPq is insufficient for a detailed analysis, it does suggest that the benefits from collaboration are not unlimited. Analysis of this data showed that scientific productivity initially grows at a rapid pace, but eventually loses momentum. This was observed even for groups with high levels of collaboration during the study period. “It might be that collaborative projects become more complex over time, and researchers’ ability to both learn and generate new and relevant knowledge is lessened,” Garcia Suggests.

Geneticist Mayana Zatz, a researcher at the University of São Paulo (USP) and head of the Human Genome and Stem Cell Research Center, one of the 17 FAPESP-funded Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDC) in Brazil, recently embarked on a project in collaboration with Brazilian pharmaceutical company EMS, as part of the Foundation’s Partnership for Technological Innovation (PITE) program. Zatz plans to use genome edition methods to generate modified pig embryos from which organs can be harvested for human transplants. If successful, the project will set up pig farms where pigs will be bred for therapeutic purposes. “At a time when government funding is in short supply, industry collaboration has become an important enabler of research funding,” she explains. “This is our group’s first public-private partnership and more are in the works.”

The oil and gas industry has been one of the biggest promoters of university-industry collaborations in Brazil, where oil companies, and notably Petrobras, are legally required to invest in R&D. “Our research requires expensive equipment, such as supercomputers and numerical tanks, but funding is available from the industry and this creates opportunities not only in exploration and production, but also across refining, the environment, and materials,” says Denis Schiozer, head of the Center for Petroleum Studies (CEPETRO) at UNICAMP. The center brings together 60 researchers working on projects that in 2019 were worth R$100 million—40% more than in 2018, and five times more than five years ago. “We were able to expand our project portfolio by advertising opportunities to faculty across the university.” Pre-salt oil expiration has created unique challenges and problems that have generated a vast number of publications, says Schiozer.

The superior productivity of researchers who collaborate with industry has a variety of underlying explanations, says physicist Vanderlei Bagnato. “When scientists tackle real-world problems in a corporate setting, they are exposed to new challenges and this yields publications with novel content,” says Bagnato, a professor at the São Carlos Institute of Physics (IFSC) at USP and head of the Optics and Photonics Research Center, another FAPESP-funded RIDC. The dynamics of collaborative research also lend to increased science output. “Every time we establish a new collaboration, we spend part of the funding on building a team of at least two or three researchers. I currently have 22 collaborative projects and a battalion of people working on them. This, of course, has a tremendous impact on the number of papers my research group publishes.” Many of the projects that Bagnato describes are being developed at a unit of the Brazilian Agency for Industrial Research and Innovation (EMBRAPII) at IFSC-USP. Funding is sourced both from the federal government and from partner corporations, with the university providing laboratory assets and researcher time.

Real-world problems in an industry setting challenge researchers to generate new knowledge

While recognizing the benefits from industry collaboration, Bagnato believes many research groups, and even high-caliber researchers, are unprepared to work on both fronts. “The rationale is entirely different from university-based research, in which any unsuccessful project can still be useful, provide insights, and be reported in scientific papers,” he explains. “A company, on the other hand, expects the project to deliver tangible results within an often short time horizon. A commitment to these results is needed or the private partner’s research goals will be frustrated,” says Bagnato, who has a policy of always assessing project risk before embarking on a project. “If the risk of failure is greater than 30%, I prefer to opt out.”

Ulisses Mello, lab director at IBM’s research laboratory in Brazil, says collaboration with universities is an essential way of injecting diversity into the corporate research environment. “Corporations and universities pursue different goals. Whereas research universities exist to train good researchers and generate new knowledge, corporations do research to create innovative products that bolster their long-term profitability. When the two sides interact, they are challenged by each other—universities offer their scientific rigor, and corporations their drive for innovation that is scalable and commercially viable. This improves outcomes for both sides.” Mello notes that much of IBM Brazil’s collaborations are with institutions where its employees received their training, including USP, UNICAMP, and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). “Interaction is virtually seamless as it builds on established links.” Academic institutions and corporations often share similar research interests. “We have an interest in nanotechnology and collaborate with the Federal University of Minas Gerais, which has strong capabilities in this field.” Mello notes that different factors will determine whether a collaboration can be effective. “This depends on the nature of the company and of the research group. We have a culture of publishing and protecting intellectual property, and work well with like-cultured universities. But if a company’s only goal is to create a new product, then collaboration can be less productive.”

Ana Lúcia Torkomian, a researcher in the Department of Production Engineering at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), sees collaboration as an essential form of knowledge transfer to society, but notes that it can only account for a limited share of innovation effort. “Most countries support the triple helix model of innovation, in which universities, corporations, and governments work together to foster and fund innovation and development,” she explains. This model extends beyond the confines of researcher-company collaboration. “It encompasses other fronts, such as creating startup incubators and technology parks within universities, or ecosystems that support innovative entrepreneurship. Launching startups around technologies spun off from university research is also important.”

Torkomian underlines the valuable role that university technology-transfer offices (TTOs) play in supporting researchers in their interaction with corporations and in licensing their technologies. “There are now over 100 TTOs in Brazil at varying levels of maturity, and they have been vital in managing intellectual property and engaging with the private sector.”

Scientific articles

GARCIA, R. et al. How long-term university-industry collaboration shapes the academic productivity of research groups. Innovation Organization & Management. Online. June 27, 2019.

MANJARRÉS-HENRÍQUEZ, L. et al. Coexistence of university-industry relations and academic research: Barrier to or incentive for scientific productivity. Scientometrics. Vol. 76, no. 3, pp. 561–76. July 2008.

BANAL-ESTAÑOL, A. et al. The double-edged sword of industry collaboration: Evidence from engineering academics in the UK. Research Policy. Vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 1160–75. July 2015.