Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp Amai menstrual pads are made of organic cotton and biodegradable bioplasticLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp

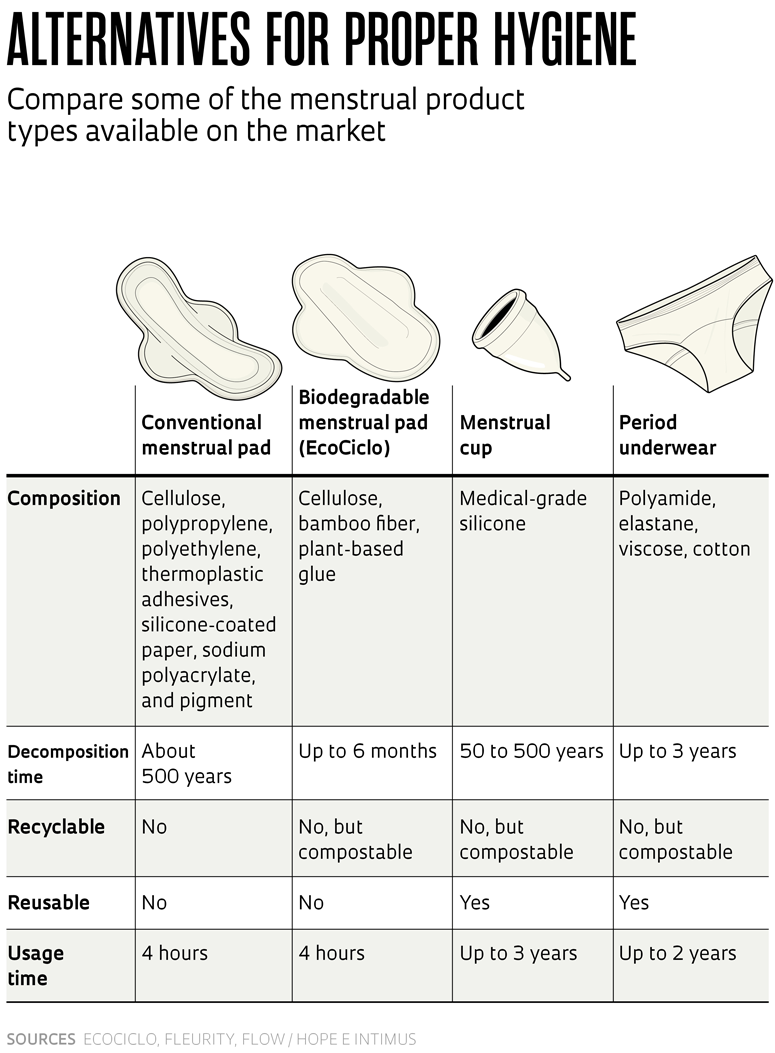

Menstruation is a physiological experience still clouded in taboo and inequalities, and surrounded by social, economic, sanitary, emotional, and even environmental issues. The sheer volume of plastic waste generated by disposable menstrual pads places a detrimental burden on the environment. Although several non-disposable and more sustainable menstrual products are currently available, such as reusable cups and period underwear, a new wave of designers, entrepreneurs, and startups is pioneering the development of biodegradable period supplies that pollute less while offering customers the same disposable convenience as conventional products.

Many of these initiatives are also helping to address the issue of period poverty, a term used to describe a lack of access to proper menstrual products and the education needed to use them effectively. Period poverty is estimated to affect over 15 million women in Brazil. These women have limited period management options that are often detrimental to their health, social interactions, and ability to show up to work.

– The challenge of period poverty

“Reusable products that require thorough cleaning won’t solve the problem of period poverty in Brazil,” says Patrícia Zanella, cofounder of Brazilian startup EcoCiclo. Zanella explains that a lack of sanitation in some regions of Brazil deprives women of proper personal hygiene and the ability to wash menstrual hygiene products. Last year, Zanella’s company received an award from the United Nations Global Compact for its pioneering biodegradable menstrual pads.

“We use raw materials that are not harmful to users’ health and decompose within six months,” explains Zanella, who holds a degree in international relations. Chemical engineer Adriele Menezes, operations director at EcoCiclo, led the research and development of the new menstrual pads. The product is manufactured by women from underprivileged areas of Salvador using bamboo fiber, cellulose, and plant-based glue.

Zanella notes that while eco-friendly options are affordable and widely advertised, women continue to use conventional disposable products. “The prevailing notion is that sustainable products are less practical, and vice versa. Our innovation offers maximum comfort and the familiar thickness, color, and absorption levels of conventional products,” she explains.

EcoCiclo’s biodegradable menstrual pads come at a unit cost of R$3, up to five times higher than conventional products available in pharmacies and supermarkets. “We have yet to develop a local solution to make sustainable menstrual products cheaper than their conventional counterparts,” acknowledges Rafaella de Bona Gonçalves, a product designer based in Curitiba. Gonçalves collaborated with EcoCiclo on her own prototype biodegradable menstrual pad.

Monyke Ruppel de AlmeidaIn addition to being used externally (left), the menstrual pad pictured below can be split into two, rolled up, and used as a tampon (center and right)Monyke Ruppel de Almeida

Initially developed as part of her undergraduate thesis at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), her ecological design garnered national and international accolades, including a second-place finish in the 2022 Young Inventors competition, sponsored by the European Patent Office (EPO). Gonçalves oversaw both the design of the menstrual pad and the material research, experimenting with cellulose, banana fiber, and soy foam. The startup team then developed the prototype. “My goal was to develop a proof of concept to demonstrate the feasibility of producing a menstrual pad with these characteristics,” says Gonçalves, noting that the product has not yet gone to market.

Her product is designed to double as a menstrual pad and a tampon. “This versatility distinguishes our design. The product can be either worn externally as a single piece or split into two parts that can be rolled into tampons.”

According to Marta Tocchetto, a retired professor of industrial chemistry from the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM) in Rio Grande do Sul, and an expert in environmental sustainability and waste management, when comparing product costs, manufacturers rarely take environmental factors into account. Polyethylene and polypropylene, prevalent in most conventional menstrual pads, are plastic polymers derived from nonrenewable and polluting fossil resources such as petroleum. Studies have shown that plastic absorbents can take up to 500 years to decompose in nature.

“After disposal, the plastic breaks down into microplastics — small polymer fragments that are harmful to the environment,” notes Tocchetto (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 281 and 332). “To make matters worse, less than half of Brazilian cities have urban landfills designed to properly process the plastics found in disposable menstrual pads.”

A research project at the Polytechnic School at the University of São Paulo (POLI-USP) estimated the environmental impact caused by menstrual pads in Brazil. The authors found that if the roughly 60 million women who menstruate in the country used disposable products during their menstrual cycles, around 15 billion plastic-based menstrual pads would be discarded annually in Brazil. As highlighted in their article, “Análise de ciclo de vida de coletores menstruais e absorventes externos descartáveis” (Lifecycle analysis of menstrual cups and disposable menstrual pads), in addition to generating significant waste, menstrual pads are often flushed down toilets, potentially causing plumbing blockages.

Some countries already have flushable period pads on the market, such as Fluus, a biodegradable menstrual pad available in the UK. It decomposes upon contact with water and within the sewage system. According to the manufacturer, even the packaging and adhesive tapes can be disposed of in the toilet. Made from plant fibers, biopolymers, and tree sap, it is sold for £0.50 (approximately R$3) per unit.