The work produced by musician Antonio José Madureira Ferreira, a native of Rio Grande do Norte, is as vast as Brazilian culture, and yet, it is not as widely known as it should be, wrote musician and historian Francisco Andrade, of São Paulo, in an article published last year in the magazine Iberic@l, Revue d’études ibériques et ibéro-américaines, distributed by Sorbonne University in France. Since 2014, the researcher has been studying the work produced by the composer who led Quinteto Armorial, and was responsible for consolidating his music collection, which was previously scattered across 12 boxes stored in the house where Madureira, now 73, lives in Recife, Pernambuco State. Now, some of his work is being published in the book Quinteto Armorial: Do romance ao galope nordestino (Editora Letra da Cidade/Çarê Institute), organized by Andrade and released last June. The first volume of the trilogy Antonio Madureira Armorial—Histórias e partituras (Antonio Madureira Armorial—Stories and scores), it features seven songs from the group’s first album, Do romance ao galope nordestino (1974), named the best instrumental album that year by the São Paulo Association of Art Critics (APCA). “Throughout his career, Madureira has created an intersection between the erudite and the popular,” says Andrade, who currently lives in Paraíba.

To understand Madureira’s journey, we must first reflect on the genesis of armorial music—a development that blossomed from what became known as the Armorial Movement, led by Ariano Suassuna (1927–2014). The term “armorial,” first used in the early 1970s by the writer, poet, and playwright from Paraíba, alludes to a concept aimed at rethinking the Northeast as a space for new types of aesthetic creation. Suassuna began using the word, which in its original sense means “a book for registering coats of arms,” as an adjective, inaugurating a movement that intended to reinterpret Brazilian cultural traditions, such as cordel literature, xylography, cantoria music, and the use of instruments such as the viola, rabeca, and pífano. “Music was one of the most fruitful fields for armorial research and creation,” Andrade writes in the book.

The Armorial Movement officially launched on October 18, 1970, at the São Pedro dos Clérigos Church, in Old Recife, with a visual arts exhibition and a concert by the Pernambuco Chamber Armorial Orchestra, which made its debut two months earlier. The following year, the first encounter between Suassuna, then a professor of aesthetics, Brazilian culture, and philosophy at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), and Madureira, who was 21, would change the history of armorial music. The young man had studied guitar at UFPE’s Pernambuco School of Fine Arts, and since 1969 he had worked as a guitarist and composer at the Popular Theater of the Northeast (TPN). He was inspired by modernist Mário de Andrade’s (1893–1945) reflections on Brazilian music and culture, when Suassuna awakened in him a taste for playing the northeastern viola, as well as an affinity for listening to northeastern music and researching its popular culture, including folguedo celebrations and their Iberian roots (Christian, Arab, and Jewish).

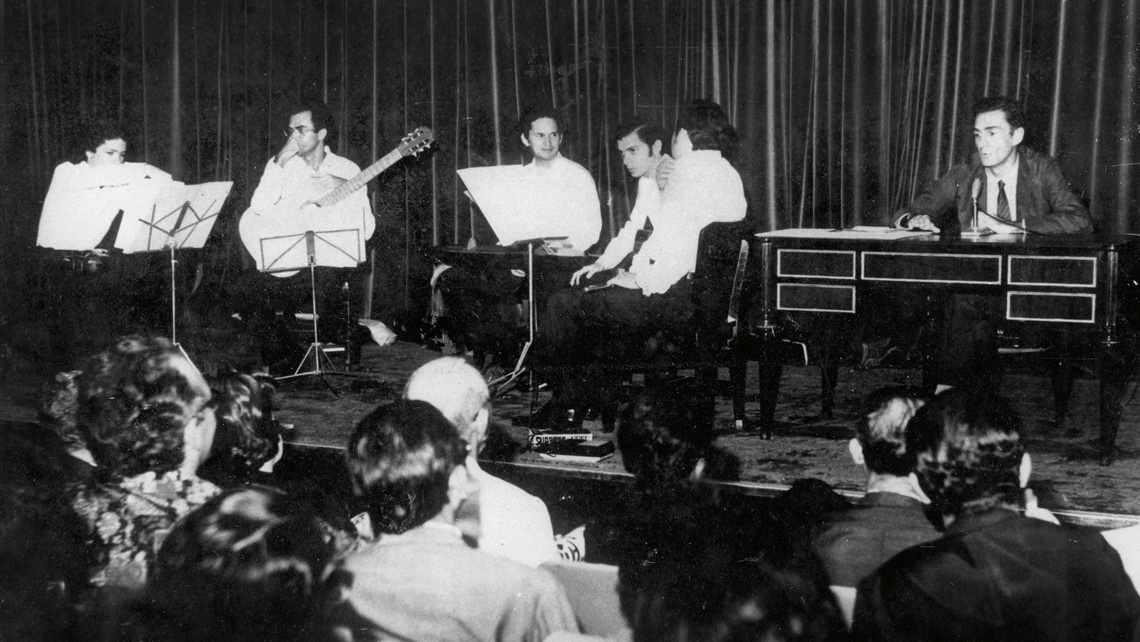

Joaquim Nabuco Foundation

The group in a photo from the 1970s; Madureira is second from the leftJoaquim Nabuco Foundation“Suassuna thought Orquestra Armorial, led by Cussy de Almeida [1936–2010], had a very European quality,” notes Ariana Perazzo da Nóbrega, a professor at the Federal University of Paraíba’s (UFPB) Music Department and author of the master’s thesis titled “Music in the Armorial Movement.” Defended in 2000 at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), it is one of the first academic studies on the subject. Madureira was largely responsible for shaping Quinteto Armorial (1972–1980), bringing sertanejo (badlands) music to concert halls, proposing a broader discussion of popular culture, music, and what it means to be northeastern. “According to Suassuna, the work produced by Quinteto Armorial was the most significant to the movement’s music, as it sought to bring the sertanejo universe centerstage, using instruments such as the pífano, the rabeca, and the northeastern viola,” continues Nóbrega.

In addition to the album Do romance ao galope nodestino, the quintet has recorded three other albums: Aralume (1976), Quinteto Armorial (1978), and Sete flechas (Seven arrows, 1980). The longest-lasting lineup featured Madureira (northeastern viola), Antonio Nóbrega (violin and rabeca), Edilson Eulálio Cabral (guitar), Egildo Vieira do Nascimento (flute and pífano), and Fernando Torres (marimbau). All the LPs were released under the independent São Paulo label Discos Marcus Pereira (1974–1981), known for recording popular events in various Brazilian regions and for having recorded samba musicians such as Agenor de Oliveira, Cartola (1908–1980), and Paulo Vanzolini (1924–2013). According to Andrade, the quintet recorded one of the tracks on their first album along with two fans of the instrument ensemble’s work: Vanzolini himself and musician Geraldo Vandré. At the time, Aluízo Falcão, the record’s producer, asked the group’s members and the two guests what they thought of incorporating the bombo, a percussion instrument, into the musical arrangement. Vanzolini, who was also a zoologist and the director and researcher of USP’s Zoology Museum, responded: “I don’t have any thoughts, I only know about lizards.”

The three-book series derives from Andrade’s master’s thesis, defended in 2017 at the University of São Paulo’s Brazilian Studies Institute (IEB-USP). He is currently conducting doctoral research at UFPB on Madureira’s music and is preparing the remaining two volumes on the composer from Rio Grande do Norte. Due to be released at the end of November, the second volume covers the period between 1975 and 1981 and addresses, among other things, the relocation of Quinteto Armorial members. They worked as research musicians at UFPE but relocated to the newly-formed Cultural Extension Center at UFPB, based in Campina Grande and focused on teaching and researching popular Brazilian music. Egildo Vieira do Nascimento has been replaced by Antonio Fernandes de Farias, known as Fernando Pintassilgo (flute and gaita dos caboclinhos). Hired as music professors, they remained at the institution from 1978 to 1981. The third volume, whose topics include an exploration of armorial music’s significance in the present day, discusses Quarteto Romançal, a group that was formed after Suassuna became the Pernambuco State Secretary of Culture in 1995, creating a project called “Pernambuco Brazil,” with Madureira’s input. The publication is due to be released during the first half of 2024.

According to Andrade, the book series aims to compile 40 of Madureira’s compositions, recorded on six albums—four by Quinteto Armorial and two by Quarteto Romançal, Quarteto Romançal (1997) and Tríptico – no reino da ave dos três punhais (1999), both released under the Ancestral label. “This collection was intended to more widely circulate his work, to facilitate its availability to musicians who want to play it, and to break down barriers within music halls and colleges that still insist on treating only European composers’ work as chamber music,” writes viola player Ivan Vilela, professor at USP’s School of Communications and Arts’ Music Department, in the introduction to the first volume in the trilogy.

Violinist Rucker Bezerra de Queiroz, professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte’s (UFRN) School of Music, has focused his research on investigating the Iberian and Arabic influences of armorial music. “I decided to take the opposite route to Luis Soler [1920–2011], Catalan violinist who lived in Recife for a long time before becoming a professor at Santa Catarina State University [UDESC],” he says of the author of Origens árabes no folclore do sertão brasileiro (Arabic origins in Brazilian badlands folklore; Editora UFSC, 1995). “It was in Brazil that Soler became aware of the Moorish influence on the Iberian Peninsula. When he arrived in Recife, he saw repentistas (Brazilian poets who sing their own improvised verses to the sound of the viola or fiddle) playing the viola and said: ‘This was going on in the streets of Barcelona when I was growing up,’” recounts Queiroz, who researched the subject in Spain and in Arab countries. “During my performances in places like the United Arab Emirates, the audience was amazed, and many people said to me: ‘This isn’t Brazilian music, it sounds like our music, but just a bit different.’”

Joaquim Nabuco Foundation

Quinteto Armorial and Ariano Suassuna performing together in Recife, in 1972Joaquim Nabuco FoundationAccording to Erik Pronk, professor at UFPB’s Music Department, one must not, however, idealize a harmonious relationship between the Iberian, African, and Indigenous elements present in armorial music, as if the three cultures that formed the country were on equal footing. “The popular expressions that Madureira sought to defend in his armorial music reflect various traces of resistance by Indigenous cultures, which carry within them the imprints of conflict among the different peoples who were part of forming the Brazilian nation. All the violence related to these conflicts is still very evident in our society today,” he says.

Pronk turned his attention to armorial music between 2008 and 2010, when he was studying for a master’s degree in classic guitar at the Royal Conservatoire in the Netherlands. It was there that he first became interested in the viola as an instrument. “Being far from Brazil somehow brought me closer to a greater sense of identity and belonging to Brazilian culture,” he says. The viola, explains the researcher, is associated with the image of the traditional singer, who uses the instrument as an accompaniment to tell stories through singing. The marimbau, according to Pronk, is “the movement’s ‘most armorial’ instrument.” It was designed by the quintet’s members based on the berimbau, which is an example of how “people with few material resources and without access to conventional musical instruments transform everyday objects into expressive media, so that they can perform on local stages, usually in town squares and at street markets.”

In 2016, Pronk began his doctoral research at the Aveiro University’s Communication and Art Department, in Portugal. The study had three central pillars: the Brazilian viola, armorial music, and live looping, a technology used during performances that allows music arrangements to be developed in real time by repeating recorded pieces. As a follow-up to his dissertation, defended in 2021, the researcher wrote a chapter for the book Live looping in musical performance: Lusophone experiences in dialogue, released this year by the British publisher Routledge. The text discusses the adaptation of Madureira’s song “Repente” for a performance using loops. “I contextualize the northeastern repente genre, highlighting how it appears in Madureira’s composition, and describe my process of creative experimentation with the help of technology,” he explains. “It’s a way of showing that Madureira’s music is more and more alive.”

Kika Antunes

Madureira in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, during the 2nd Historic Music Festival, in 2016Kika AntunesAccording to ethnomusicologist Carlos Sandroni, professor at UFPE’s Music Department, Madureira belongs to the pantheon of Brazilian music composers who push the boundary between erudite and popular. According to the scholar, this group includes Ernesto Nazareth (1863–1934), Pixinguinha (1897–1973), Tom Jobim (1927–1994), Egberto Gismonti, Hermeto Pascoal, and Guinga. “Armorial music has a very clear connection with the pursuit of classical Brazilian music inspired by the people,” says Sandroni, who is also a professor at UFPB’s Graduate Program in Music, where he is currently supervising Andrade’s doctoral research. “Many twentieth-century composers did this, but armorial was different, because the means of dissemination was not the score but the recording. Only now are Madureira’s scores coming out. In other words, armorial music dissolves, in its own way, the boundaries between the popular and the erudite.”

Republish