Brazilian participation in the 7th World Conference on Scientific Integrity, in Cape Town, South Africa, shows diversification in the country of studies within this field of knowledge. Students and researchers of institutions from states such as Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Paraná, as well as the Federal District, exhibited works about ethical behavior and the incidence of misconduct in the country, experiences with training, and efforts to guarantee the reliability of scientific results.

In a plenary session on improving research data quality, Olavo Amaral, from the Leopoldo de Meis Institute of Medical Biochemistry of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IBQM-UFRJ), presented the Brazilian Reproducibility Initiative, a network of laboratories responsible for reproducing up to 60 biomedical science experiments published in Brazilian journals between 1997 and 2018—with the objective of evaluating whether the results obtained are confirmed and reliable. The results should be known by the end of the year. Amaral addressed the obstacles of conducting a project of this scale, such as the unfamiliarity of Brazilian researchers with procedures and terminology related to reproducibility and the difficulty of coordinating the associated groups while they are involved with other projects. The existence of an extensive network of laboratories and a large scientific community count in its favor, as does the availability of resources for the venture—the project received funding from the Serrapilheira Institute, as well as scholarships from the Rio de Janeiro State Research Foundation (FAPERJ) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

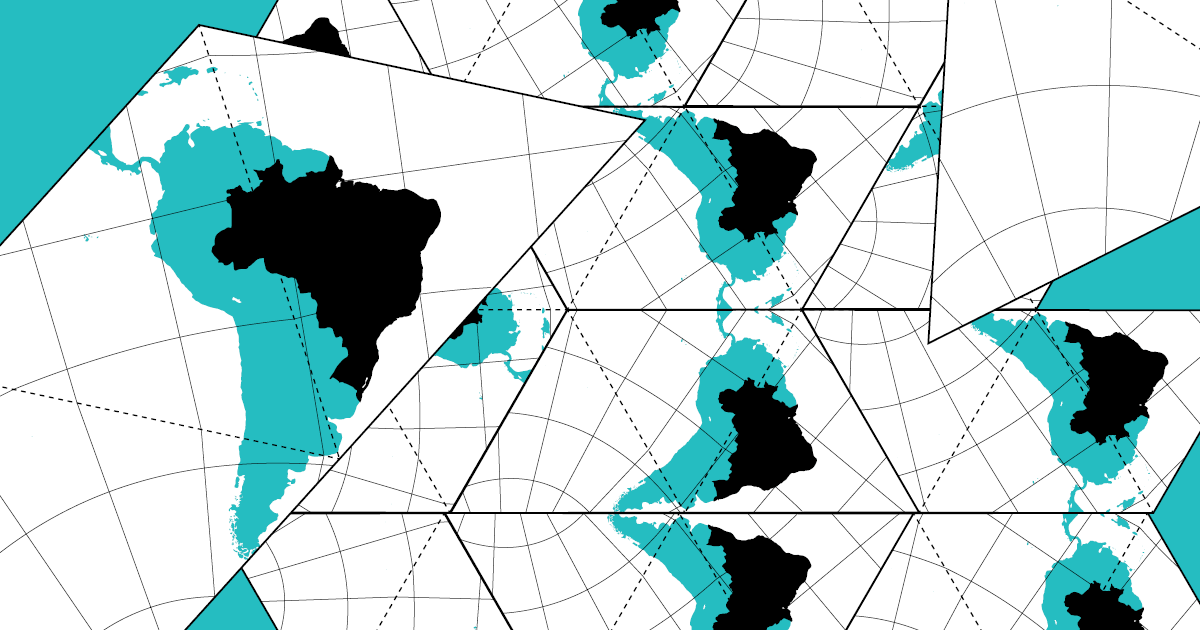

– Inequality in collaborations is a matter of scientific integrity, says World Conference

It is true that the ambitions of the Brazilian initiative are lower than those of similar projects in rich countries. While a program for reproducing cancer experiments in the USA cost US$2 million, the Brazilian project should cost a tenth of that. Another project discussed in the plenary session was the European consortium Enhancing Quality in Preclinical Data (EQIPD). Presented by biologist Björn Gerlach, from the University of Giessen in Germany, the project was idealized by universities, scientific societies, and pharmaceutical industries, and created tools and protocols to increase the transparency and robustness of data in basic research, making them more reliable for leading the development of new medicines. “Reproducibility initiatives are new and not just in Brazil. There are projects being led by networks or researchers in some countries, but none in the same mold as ours,” says Amaral.

Gabriel Gonçalves da Costa, who is doing a master’s at IBQM-UFRJ, presented a survey about transparency and integrity in 24 graduate physiology programs. He observed that the descriptions of the programs give priority to content related to the number and impact of scientific publications of their researchers, to the detriment of the concepts of transparency and integrity. Courses related to the reproducibility of science and similar topics are rare, according to the work.

The existence of databases about scientific articles invalidated by errors or misconduct fueled the analyses of dozens of works presented at the conference, including some from Brazil. Mariana Dias Ribeiro, also from the IBQM-UFRJ, addressed the influence of the retractions of papers on the careers of scientists in countries that lead academic production in biomedical studies. As part of her PhD in progress, Mariana spent six months at the University of California, San Diego, where she carried out a survey with 224 researchers that worked as reviewers on panels for US funding agencies, such as the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. In general, she observed that the fact a researcher has had a work retracted, for misconduct, for example, had no influence on the evaluation they received. “The correction of research registers, due to an honest mistake or misconduct, was seen by the interviewers as an important mechanism for strengthening the reliability of science, but this is not a factor that, until now, has objectively influenced the review of projects,” said Ribeiro.

Information scientist Edilson Damásio, librarian of the State University of Maringá, in Paraná, took two contributions to the poster session. One of them analyzed retractions of studies by researchers from Brazil published between 2016 and 2021, registered in the Retraction Watch database. In total, 116 retracted articles were identified. The most represented fields were medicine (25), biochemistry (18), and biology (11), among others. “The incidence of cases of plagiarism, falsification, and fraud is lower than in other countries, but drew attention to the number of articles retracted for duplication of images and results—which probably has something to do with splitting results in different publications to increase academic productivity,” says the information scientist.

Damásio also interviewed 209 editors of Latin-American periodicals from the SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online) library to understand how they behaved when they found evidence of misconduct in works submitted for publication. Among the 82 Brazilian editors interviewed, the rate of those who rejected articles with signs of misconduct, such as the fabrication and manipulation of data and images, was high (close to 80%), but few (less than10%) took additional measures, such as communicating the evidence of ethical deviations to the institutions and funding agencies. Greater care was however taken with these developments among the editors of periodicals from other countries, such as Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Cuba, and Mexico.

Editors of health journals prefer guiding authors rather than rejecting articles

SciELO is a library created by FAPESP in 1997 that today unites almost 300 national and over 1,000 international journals—the collection was created in Brazil and its model has been adopted in several countries, mostly where Spanish is the main language. The Brazilian experience with the publication of scientific journals has become a source for studies on integrity. Edna Montero, professor at the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo (FM-USP) and the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), and editor of the journal Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira, presented a survey with 30 editors of SciELO periodicals. The results were the fruit of her final paper from the Certification in Scientific Publications course, which she took last year in the Council of Science Editors, an entity with headquarters in the USA, in partnership with the Brazilian Association of Scientific Editors (ABEC). Montero observed that the majority of the editors interviewed avoided rejecting articles that presented problems on the first analysis, preferring to return them to the authors with notes and suggestions for changes. “Seventy percent of them, for example, do not limit the number of authors per article. In some cases when there are an excessive number of authors, the manuscript is returned with the recommendation that the authorship criteria appropriate to international standards be followed. We noticed that the editors of health journals take a more guiding approach, knowing that many of these manuscripts are presented by students and that their problems are not motivated by bad faith, rather than rejecting works outright,” she says.

A member of the board of directors of ABEC, Edna Montero went to Cape Town with the president of the entity, dentist Sigmar de Mello Rode, full professor at the São Paulo State University (UNESP). A further two ABEC initiatives were presented. One showed the first experience of a distance-learning program for improving the training of editors from Brazilian journals: the scientific article evaluator course has had 418 enrollments so far. “Soon, we will launch others on editorial policies and digital identifiers,” says Rode, who is coordinating the use of the Brazilian courses in other countries with the European Association of Science Editors (EASE), an international consortium of editors of periodicals. The second study reflected a concern by ABEC with the concept of “text recycling,” which is different from plagiarism. “There is a lot of discussion about how much an author can reuse parts of texts that they themselves wrote. The reports presented by antiplagiarism software do not distinguish between recycled texts and the appropriation of other people’s ideas,” explains Rode. “This really confuses the editors of periodicals, who are seeking a magic percentage of how much similarity can be tolerated. We believe that this needs to be discussed in greater depth and for there to be different treatments for plagiarism and text recycling.”

The participation of students and researchers from the Department of Nursing of the School of Medical Sciences at the University of Brasília (UnB) stood out at the conference. Master’s student Rafaelly Stavale analyzed the presence of integrity offices and guidelines on good practice in universities and five funding agencies from Brazil. Of the 10 universities examined, only four had research integrity committees, and all five of the funding agencies had adopted guidelines for responsible practices, but only three had created institutional entities to deal with the issue—FAPESP being one of them. Stavale showed preliminary results from a review of retracted publications in health and life sciences related to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. “I have worked in ICUs [Intensive Care Units] for Covid patients and seen articles that directly interfered with my practice be retracted,” she says. The study is in progress and has tracked more than 200 canceled works—the challenge is understanding why they were invalidated, whether due to error or misconduct.

Graziani Izidoro Ferreira, who recently completed a PhD at UnB and is now a researcher in the university’s bioethics, research ethics, and scientific integrity laboratory, collaborated with Stavale for the work on retractions and presented a study about the importance of adopting methodologies for validating research of a qualitative nature in the field of nursing. “It’s a reflective work about the need to adopt greater methodological rigor and avoid subjective analysis,” says Ferreira. The study will be published as a chapter of a book. Gabriela Cantisani gave a virtual presentation of her postdoctoral project: the creation of a platform for scientific integrity training to be offered in open access, composed of five learning modules each lasting 20 minutes, aimed at young researchers and also the lay public. Dirce Guilhem, teacher at UnB and advisor to Stavale, Ferreira, and Cantisani, contributed with an overview of an integrity program applied to and validated by over 200 graduate students from UnB in areas such as health, humanities, and technology. Different teaching strategies, including the use of documentaries and films, and analysis of case studies and articles, are part of the experience in which professors act as facilitators and lecturers in Brazil and abroad, and speak about ethical conduct in research.

One of the most prolific participations was that of dentist Anna Catharina Vieira Armond. She became interested in scientific integrity during her master’s in clinical dentistry, which she completed in 2017 at the Federal University of Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri, in Diamantina, Minas Gerais. “The university attended various quilombola communities and there were a lot of doubts about the ethical dimensions of carrying out clinical trials,” she recalls. She went to Hungary for her PhD, taking advantage of contacts she had made at the University of Debrecen, where she did an internship during graduation as part of the Science without Borders program, and was able to get an international grant to work in the group of bioethicist Péter Kakuk. There, she took part in a European Union initiative to create a platform with the scientific integrity guidelines available in the member countries.

Armond presented three studies in Cape Town. One of them is about Brazil, in which she collected documents on guidelines, regulations, and policies about responsible conduct in 60 Brazilian universities. She found that 28% of them develop their own guidelines or officially adopt good practices and only 15% establish integrity office or committees. The study showed that a good part of the institutions with policies were concentrated in the Southeast and South regions. “We observed that various universities, even when they didn’t produce original documents, adopted rules provided by scientific funding agencies. Especially in those in São Paulo, the influence of FAPESP’s Code of good scientific practices is notable,” she says, referring to the guide released in 2011, which serves as a reference for researchers supported by the Foundation. The study concluded that the experiences are still unequal and heterogeneous and more institutions need to create and adopt regulatory documents.

Armond also presented research done with PhD students from nine European countries on scientific integrity knowledge. Two-thirds of the 1,500 students that answered the questionnaire had done some training about responsible conduct. Although the students who had taken courses were familiar with standards of best practices for authorship attribution, this did not result in consistent advantages when they were questioned about real problematic situations. A third study showed the results of a survey done with 438 PhD students, postdoctoral researchers, and teaching staff from the universities of Debrecen, Szeged, and Miskolc, in Hungary. It showed that researchers early in their careers, including postdoctoral researchers and teaching assistants, had the most negative perception of the atmosphere of integrity and the pressure to publish results. Armond is moving to Canada, where she will take a postdoctoral fellowship in scientific integrity at the University of Ottawa.

Republish