Brazilians are increasingly opting for apartment living, a trend highlighted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’ (IBGE) latest Demographic Census for 2000–2022. The surge in high-rise development, which is rapidly reshaping urban skylines, has been driven by different factors in different cities. In metropoles like São Paulo and Porto Alegre, for instance, urban planners and architects observe a trend of relaxed zoning regulations, bending to the dynamics of the real estate market. This is in contrast to Rio de Janeiro, where building-height restrictions have remained largely unchanged since the 1970s.

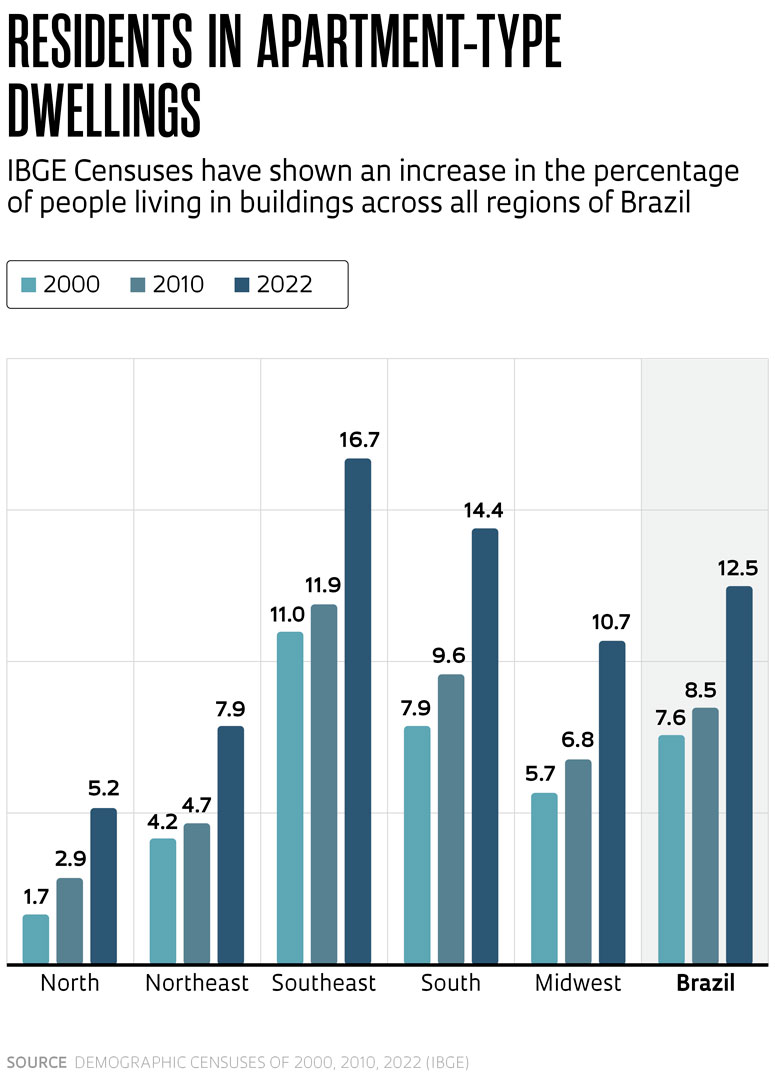

IBGE defines apartments as dwellings within multi-story buildings featuring common grounds and amenities, like lobbies, staircases, or corridors connecting different units. Despite Brazil being predominantly a nation of house owners, with 84.8% of Brazilians residing in houses, the latest Census revealed a notable increase in apartment dwellers, rising from 7.6% (in 2000) to 12.5% (in 2022). Surprisingly, the three top-ranking cities in this shift aren’t the bustling metropolises: Santos (SP), Balneário Camboriú (SC), and São Caetano do Sul (SP) have over half their residents living in apartments.

Bruno Perez, a geographer and analyst at IBGE, attributes Santos’s high-rise growth to its insular geography, with most of the island-city’s real estate already developed. “This has led to a natural expansion upwards,” he suggests. In Balneário Camboriú, the real estate boom is tied to tourism. “Pristine coastal areas are prime for vertical development to attract homebuyers looking for beachside properties. The city’s coastline is an extreme case of high-rise development,” he says. Unhampered by height restrictions, the city’s 290-meter skyscraper overlooking Atlântica Avenue holds the record for Brazil’s tallest building. São Caetano do Sul, one of Brazil’s smallest cities by area, was developed primarily through high-rise construction, partly driven by its proximity to São Paulo.

Analyzing the 2022 Census data, João Fernando Pires Meyer from the School of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of São Paulo (FAU-USP), notes that while urban verticalization is a nationwide trend, it is more pronounced in the South and Southeast. “About 70% of the country’s high-rises are concentrated in just 66 cities,” Meyer says.

diegograndi / Getty ImagesIn Porto Alegre, zoning regulations have been relaxed to accommodate real-estate market interestsdiegograndi / Getty Images

Among them, São Paulo and its surrounding cities—including Guarulhos, Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, Santos, and Campinas—account for half of Brazil’s apartment buildings. Between 2010 and 2022, São Paulo alone saw over 60,000 new high-rise homes developed annually. In its larger Metropolitan Region, it was double this figure. “The region’s verticalization stems from São Paulo’s urban density, as available land for traditional housing is in short supply. So the only room for city expansion is upward and outward to neighboring cities,” says Meyer.

“In clusters of adjoining cities, the high-rise trend has been growing since 2010,” says Angelo Salvador Filardo, a professor of architecture and urban planning at FAU-USP, who has led a research group on high-rise development and urban densification in Brazilian cities since 2017. This expansion of major cities or metropolises to a point where they are fused with neighboring cities is termed “conurbation” by researchers in the field. Other examples of conurbation include the regions of Vitória and Vila Velha in Espírito Santo; Natal and Parnamirim in Rio Grande do Norte; and Curitiba and São José dos Pinhais in Paraná, as noted by Ângela Luppi Barbon, an architecture and urban planning professor at FAU-USP.

Between 2008 and 2018, the IBGE upgraded three new Brazilian cities to metropolises: Florianópolis, Vitória, and Campinas. A metropolis, as defined by the institute, is a large city that exerts influence over the surrounding urban space, acting as a hub for the flow of people, goods, information, and capital.

“The early spread of high-rise development in Brazil correlates with a period of increased industrialization and urbanization in the 1970s, when urban populations surpassed rural ones,” explains architect and urban planner Manoel Lemes da Silva Neto from the Catholic University of Campinas (PUC-Campinas). In that decade, 56% of Brazilians lived in cities, compared to the 84.36% reported in 2010 by the IBGE.

Another factor driving high-rise development in the 1970s was technological advancements in the construction industry. “Elevator capacity and building systems improved, enabling the construction of progressively taller buildings,” notes Luciana Nicolau Ferrara, a professor of architecture and urban planning at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC). In 2023, Ferrara completed a FAPESP-funded research project that explored the interface between the São Paulo real estate market and environmental concerns. According to Ferrara, new real estate financing options, changes in zoning regulations, and the financial interests of major construction firms and developers have all played a role in the current high-rise trend.

Cibele Saliba Rizek, a sociologist at the Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning (IAU) at USP in São Carlos, notes that up to the mid-1970s, São Paulo’s real estate market dynamics were primarily driven by individual property transactions for residential use. “The landscape has since changed. Today, many developments are designed to attract investors seeking real-estate assets,” explains Rizek, who has researched the development of Brazilian cities and low-income housing programs.

“The current vertical urbanization process in São Paulo is creating what we term a ‘hollow city,’” suggests Silva Neto of PUC-Campinas, referring to a concept coined by Anderson Kazuo Nakano, a professor of architecture and urban planning at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). Nakano uses this metaphor to describe how many new buildings are sparsely occupied. According to census data, São Paulo had 290,000 vacant houses or flats in 2010, a figure that rose to 588,000 in 2022, representing a 103% increase.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPVerticalization in São Paulo has primarily taken the form of mid-range and high-end buildings in neighborhoods with subway stationsLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Vertical growth has different drivers and comes in different forms from one city to another. São Paulo has the highest number of apartments in Brazil at 1.4 million units; approximately 29.4% of its population now lives in apartment buildings, according to the 2022 Census. The municipal government developed its first Master Plan in 1971, followed by successive revisions over the decades. The changes enacted in its 2014 edition were widely hailed as a step in the right direction by the city’s leading urban planners and architects.

The new concept was well-intended, say researchers. “Compact, dense cities operate more efficiently and sustainably,” says Meyer of USP. “Dense urban arrangements reduce the need for travel and, consequently, individual vehicle usage, while also mitigating pollution and energy costs.” The 2014 Master Plan (Law No. 16,050) introduced guidelines to encourage greater concentrations of residents along mass-transit corridors, and expanded height limits for buildings in these zones. Apartments within this concept have an average 80 square-meter (m²) footprint and come with only one parking space. “The goal is to develop housing that caters to different social profiles along a backbone axis—an area furnished with good infrastructure and mass transit,” notes Manoel Rodrigues Alves, an urban planner and architect at IAU-USP in São Carlos.

However, the primary objectives of the 2014 Master Plan have not been met, according to Alves and Meyer. Many new developments near subway stations, for instance, have failed to incorporate affordable housing units. Instead, mid-range and high-end buildings have been erected, as seen in neighborhoods like Vila Madalena and Pinheiros in São Paulo’s West Side. “Construction firms and developers have exploited loopholes in zoning regulations to develop projects aligned with their commercial interests,” says Alves. In 2021, he concluded a FAPESP-funded research project investigating high-rise development and its purported role in building more inclusive cities, absorbing population growth, and curbing urban sprawl.

Maira Erlich / Bloomberg via Getty ImagesAtlântica Avenue in Balneário Camboriú: the city’s zoning regulations have no height limits for developments along this avenueMaira Erlich / Bloomberg via Getty Images

The real-estate market has responded to the new guidelines with developments featuring studio-type apartments near subway stations. Despite their compact size—less than 80 square meters—they boast balconies with barbecue areas and communal amenities such as party halls, gyms, and pools, enhancing property value. With the current ban on apartments with more than one parking space each, some developers have purchased adjacent lots to create parking facilities that can then be leased to future residents of the development.

The latest revision of São Paulo’s Master Plan, in 2023, has increased the average size of apartments and the number of parking spaces in developments along high-density backbone axes. This has attracted high-end developments precisely near the city’s subway stations, notes Meyer of USP. “The current Master Plan is more aligned with the interests of the real estate market, and the essential tenets of the 2014 Master Plan have been abandoned,” he adds.

Eduardo Marques, a political-science researcher at the USP Center for Metropolitan Studies (CEM), a FAPESP-funded Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Center (RIDC), conducted a survey on the São Paulo real estate market based on property-tax data over the period 2000–2020. Unlike the IBGE Census, which quantifies locations serving as housing for one or more individuals, whether titled or not, Marques’s study focused on the stock of titled properties—residential properties that have been legalized by the municipal government—including those not necessarily being used for residence. He excluded, for instance, any untitled houses in favelas, whereas these were included in the IBGE Census. Marques found that, when considering only titled properties, São Paulo now has more apartments than it does houses.

In 2000 the city had 1.23 million houses, a figure that climbed to 1.37 million by 2020—an increase of 11.8%. Meanwhile, apartments surged from 767,000 units in 2000 to 1.38 million in 2020, an 80% increase over the period. “From 2000 to 2020, we observed an uninterrupted trend of verticalization throughout the city,” notes Marques. He adds that during this timeframe, the city saw two different master plans and two zoning laws. “These regulations accelerated the high-rise trend in some neighborhoods, but the city as a whole was already undergoing a process of vertical expansion,” he says. According to the survey, mid-range buildings have been the main drivers of urban growth over the past 20 years, followed by high-end developments.

Cristian Lourenço / Getty ImagesIn Rio de Janeiro, master plans have been developed with a view to preserving the cityscapeCristian Lourenço / Getty Images

The relaxation of zoning regulations to accommodate real-estate market interests also helps explain the vertical growth trend in Porto Alegre, according to architect and urban planner William Mog. In his doctoral thesis, defended in 2022 at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Mog analyzed formal real-estate market data in a study similar to Marques’s. Porto Alegre has the fifth-highest percentage of people living in apartments, according to the IBGE’s 2022 Census, with 42% of its residents residing in this type of housing. Based on property-tax data for 2000 to 2019, Mog found that apartments accounted for 60% of the square footage built during the period. “This reflects recent amendments to the city’s urban planning regulations. Master plans were adapted to accommodate a high-rise land-use model,” says the researcher.

He cites as examples the verticalization of sections of the city’s North Side, which until 2000 were environmental protection areas or originally industrial areas barred from real estate development. “In these areas, we have observed a proliferation of developments primarily targeting individuals with low to moderate purchasing power,” he says. “These buildings have increased population density in the outer areas of the city, significantly affecting urban mobility,” says Mog, an architect and urban planner at the Operational Support Center for Urban Planning and Property Affairs, run by the State Public Prosecutor’s Office. Many of the regulatory changes that eased restrictions on vertical development were not implemented through master plans but through specific laws that altered land-use zoning for new real estate developments.

In contrast to São Paulo and Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro’s master plans have consistently placed a cap on building heights in the city, says Rogerio Goldfeld Cardeman, a professor of architecture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). As a coauthor of the book O Rio de Janeiro nas alturas (Rio de Janeiro’s high-rise; Mauad, 2019), Cardeman has researched the city’s zoning regulations from the arrival of the imperial court of Dom João VI (1767–1826) in 1808 to the present. Rio’s vertical urbanization, he says, began in central areas as early as the nineteenth century. The construction of the city’s tram system in 1859 accelerated this process and expanded it to other areas of what was then Brazil’s capital. It was during this period that middle- and upper-income residents started purchasing small plots of land on the North Side, such as on former sugar mill properties. On the South Side, multistory development began in the early twentieth century in Copacabana and expanded in the subsequent decades to Ipanema and Leblon, consisting primarily of mid-rise buildings on small lots.

With its first master plan dating back to 1988 and the latest edition enacted in early 2024, Rio is among the 15 Brazilian cities with the highest percentages of residents living in apartments, at 36%. However, its zoning regulations have maintained strict building-height limits. “Since the 1970s, in neighborhoods like Ipanema and Copacabana, for example, the limit has been 18 floors,” says Cardeman. An exception, he notes, is Porto Maravilha, a project to revitalize the city’s port area in 2011—here, buildings up to 150 meters in height, or about 40 stories, were exceptionally permitted. “Rio’s master plans have been developed with a view to preserving the landscape and cityscape,” explains Cardeman.

One of the measures taken in Rio was the creation of Cultural Environment Protection Areas in 1992, under a law supplementing the Master Plan. This law requires urban clusters representative of the city’s different stages of development to be preserved in their as-developed state. Thus, in neighborhoods like Catete and Jardim Botânico, for example, the maximum height for new buildings is lower than in other areas of the city. “The lower buildings, blending into the surrounding cityscape, tend to induce people to interact more with public spaces and enjoy the building-front sidewalks. Conversely, large developments surrounded by walls and guardhouses, with abundant parking spaces, tend to isolate citizens from everyday life in cities,” concludes Cardeman.

Project

Storm surge and coastal flood warning system for the coast of São Paulo, focusing on the impacts of climate change (no. 18/14601-0); Grant Mechanism Public Policy Research; Principal Investigator Celia Regina de Gouveia Souza (IPA); Investment R$403,406.76.

Scientific articles

KOERICH, M. P. & PEREIRA, P. S. Assessing the impacts of coastal engineering structures on the coastline of Santa Catarina state, southern Brazil: A geospatial aproach. Ocean and Coastal Management. vol. 245, 106858. oct. 31, 2023.

LEISNER, M. M. et al. Long-term and short-term analysis of shoreline change and cliff retreat on Brazilian equatorial coast. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. vol. 48, no. 14, pp. 2987–3003. nov. 2023.

SAENGSUPAVANICH, C. et al. Jeopardizing the environment with beach nourishment. Science of the total environment. vol. 868, 161485. apr. 10, 2023.

SIEGLE, E. & Costa, M. B. Nearshore wave power increase on reef-shaped coasts due to sea-level rise. Earth’s Future. vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 1054–65. oct. 2, 2017.

SILVA, P. L. da & LINS-DE-BARROS, F. M. A alimentação artificial da praia de Copacabana (RJ) após 51 anos. Terra Brasilis. vol. 16. dec. 5, 2022.