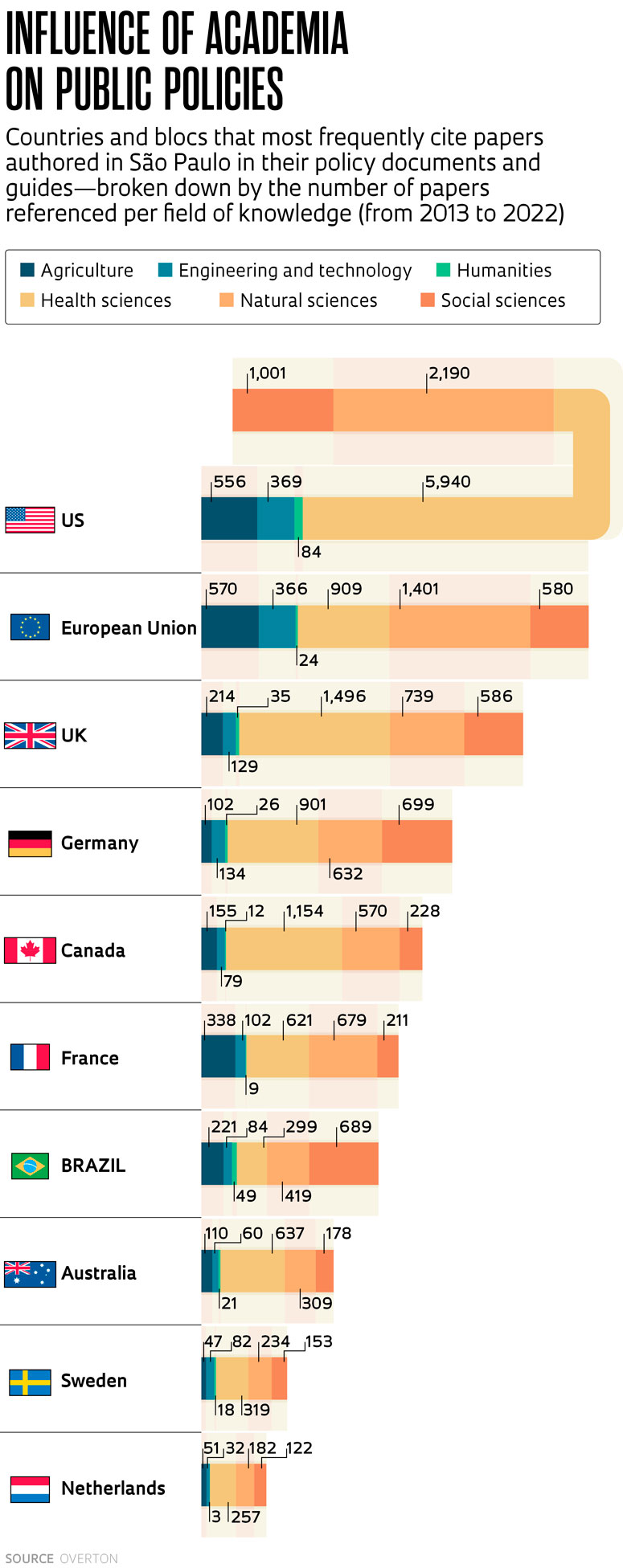

Research papers produced in Brazil — particularly in fields such as climate change, the Amazon, and biofuels — are among the most widely cited in public-policy proposals and reports in countries such as the US, the UK, and Germany. According to data compiled from Overton, an international database of policy documents and associated research, a total of 25,391 papers authored by São Paulo–based researchers were cited in 33,398 policy documents from 1,017 different government agencies, intergovernmental organizations, and think tanks across 123 countries from 2013 to 2022.

“Our interest is in examining the societal benefits from São Paulo’s research output beyond academia, and this database offers insights into how this research has shaped public policy for the benefit of society,” explains agricultural scientist Connie McManus, international relations manager at FAPESP. She conducted the study in collaboration with Niels Olsen Câmara, an immunology researcher at the University of São Paulo (USP) and an advisor to FAPESP’s Scientific Board. “Our findings underscore the significant influence that São Paulo’s researchers have over public policies in Brazil and globally,” she adds.

Among the intergovernmental bodies regularly citing research out of São Paulo are the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Commission, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization(FAO), and the World Bank. Interestingly, among the top 25 sources referencing Brazilian studies, 23 are international, with only two domestic sources — the Federal Government and the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), a government-policy think tank under the Ministry of Planning. “IPEA’s core mission is precisely to produce data to inform improvements to public policies. Our research draws heavily on this data,” explains economist Fernanda De Negri, who heads the Center for Research on Science, Technology and Society at IPEA.

Brazil trails the US, the European Union, the UK, Germany, Canada, and France in the number of public-policy references to research conducted in São Paulo. McManus suggests that Brazilian government agencies may not be basing their public policies on scientific research to the same extent that organizations in other countries are. “Perhaps our researchers should seek to publish their findings in a language that will support greater uptake by policymakers,” she proposes.

The survey also explores the topics of Brazilian research that are most widely cited in foreign policy documents. In engineering and technology, subjects like biofuels and greenhouse gas emissions are the most commonly cited. In natural and social sciences, the Amazon is a recurrent theme. In medical sciences, studies on tropical diseases and the adverse effects of ultra-processed foods are among the most highly cited, while in agriculture, research on tilapia, citrus, eucalyptus, and the genetics of pests such as Xylella fastidiosa is the most prevalent. Lastly, the study identified the most widely cited researchers from institutions in São Paulo in international policy documents. Topping the list, with 137 cited documents, is Paulo Artaxo from the USP Institute of Physics, renowned for his work on aerosols and his contributions to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “Brazilian research holds significant influence in international reports, and there are research domains in which we are globally leading authorities,” says Artaxo, noting, for instance, Brazil’s contributions to climate-change research. “Brazil is second only to the US in terms of the number of researchers providing inputs into IPCC reports.”

Several names on the list feature prominently in prestigious academic rankings, such as Clarivate Analytics’s annual Highly Cited Researchers list. Among them is Carlos Augusto Monteiro from the School of Public Health at USP, a pioneer in research on ultra-processed foods (see interview), with 130 citations; Pedro Henrique Brancalion, an authority in tropical forest restoration at USP’s Luiz de Queiroz School of Agriculture (ESALQ), with 82 citations; and psychiatrist André Brunoni from the School of Medicine at USP, who leads studies on depression, with 70 citations (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 310).

McManus and Olsen Câmara also compiled data on Brazil’s overall performance in the Overton database, which mirrored their findings for São Paulo in terms of citing institutions and countries and the domains in which Brazil is most influential. “This comes as no surprise, given that São Paulo researchers have accounted for over 40% of Brazil’s science output in recent years,” notes McManus. Research produced through international collaborations had a 71% higher likelihood of being cited in reports.

Sociologist Ana Cláudia Niedhardt Capella, a public policy expert and researcher at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Araraquara, notes that in recent years Brazil’s science output has been increasingly targeted toward solving complex societal issues, ranging from inequality to challenges related to violence, healthcare access, and education. Not only has there been a surge in academic capacity, but governments are also increasingly looking to enhance their policies and return on investment.

“It’s heartening to learn that Brazilian public-policy research has garnered international acclaim, yet we still have ground to gain,” remarks Capella. “We must deepen collaborations between researchers and policymakers to ensure that the research we produce is not only increasingly used to inform policymaking in Brazil, but is also more attuned to the public issues on governments’ agendas.”

Republish