Are we experiencing an outbreak of Brazilian spotted fever? “Not at all!” was the emphatic response from Marcelo Labruna, a researcher from the School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science at the University of São Paulo (FMVZ-USP), when posed the question by Pesquisa FAPESP. He is currently on a field trip in São Paulo with his British colleagues, collecting ticks to determine whether different types of vegetation provide more or less favorable conditions for harboring these arachnids, the primary carriers of the spotted fever bacterium. Labruna is quick to dismiss the notion of an epidemic, saying if there is one, it is of misinformation. “I’ve dedicated three decades to studying Brazilian spotted fever — a disease that is little-known both to the at-risk population and to the medical community,” he says.

First and foremost, he adds, people should know that Brazilian spotted fever is treatable. It can be fatal if left untreated, but not overnight. “If I were to develop a sudden fever after a day of fieldwork, I know that I have a two- to three-day window to start antibiotic treatment — plenty of time not to panic,” he reassures. The initial symptoms are nonspecific, primarily fever and headache. The distinctive skin lesions may surface a fortnight later, by which time the Rickettsia rickettsii bacterium has already taken its toll on the vascular system, and the efficacy of treatment may be compromised. It is important that people inform their physicians if they have been in areas where the disease is prevalent — such as pastureland, sugarcane fields, or areas known to harbor capybaras. When administered promptly, the prescribed medication ensures a smooth recovery.

Taking antibiotics preventively is not recommended, says Labruna. While antibiotics impede bacterial multiplication, only the patient’s immune system has the ability to eliminate the pathogen. Hence, treatment should only commence once the body’s natural defenses have mounted a response.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPCayenne ticks perch on plants from which they can attach to passing animalsLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Labruna also underscores the importance of removing ticks as soon as possible. Transmission of the bacterium requires prolonged contact, as explained in a series of educational videos created for young audiences by Gabriela Bragagnollo, a researcher at USP’s Ribeirão Preto Nursing School. “People living in cities are often oblivious to ticks,” says Labruna, adding that he is quick to remove them after a bite. Despite his frequent exposure, this precautionary measure prevents him from contracting the disease.

Are capybaras the culprits?

Capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), the largest rodents in the world, are the primary reservoirs of the disease-causing bacterium in terms of biomass. They often coexist in close proximity to humans due to their ability to adapt their diet to a variety of plants, thriving even in areas altered by human activity, as evidenced in a recent publication from Labruna’s research group, featured in the February issue of the Journal of Zoology.

However, capybaras are not very efficient amplifiers of this bacterium for several reasons. One is their development of immunity after an initial infection, which prevents sufficient bacterial multiplication in their cells and consequently limits transmission to Cayenne ticks of the Amblyomma genus, the vectors responsible for infecting humans, as shown in a study led by Labruna, published in 2020 in Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. The bacterium can only continue its cycle of contagion in capybaras if there are young animals or newcomers that have not been exposed to the disease.

Despite their association with a significant portion of severe infections in individuals who come into close contact with them, culling capybaras is not a viable solution. Labruna puts it simply: as rodents, they readily reproduce when food is abundant, which is what happens when a portion of the population is removed. “And having young individuals in the group, without prior exposure, is precisely what the Rickettsia bacterium wants,” he humorously remarks.

Tick pesticides are equally impracticable. The few available products are challenging to administer to wild animals, and since capybaras spend a significant portion of their time in water, the product would dissolve in the water and would not stay for long in their fur.

To prevent the repopulation of an area with new arrivals that are susceptible to the disease, Brazilian law prohibits the killing of these animals other than in remote areas. Erecting an impervious barrier would be equally challenging, and completely eradicating capybara populations in extensive areas is all but impossible. The approach favored by the veterinarian’s group involves sterilization through tubal ligation and vasectomy, a strategy that has yielded promising results in areas of São Paulo State where Brazilian spotted fever is endemic. This method prevents reproduction but does not eliminate the hormonal instincts that drive these animals to defend their territories. This ultimately results in more effective isolation compared to relying solely on physical fencing. “When we reduce birth rates by 80%, the bacterium disappears from the population within five years,” says Labruna. However, at a larger scale, this strategy becomes logistically prohibitive.

Luciano Verdade, a crop science researcher affiliated with the Center for Nuclear Energy in Agriculture (CENA) at USP, notes that capybaras are not the only hosts of the Cayenne tick. Birds and snakes, for instance, can also serve as hosts, and if they migrate to a new area with one of these arachnids nestled among their feathers or scales, they could potentially introduce the tick and its bacteria into the area, infecting other animals. “If an atomic bomb were to detonate in the state of São Paulo, capybaras, ticks, and the Rickettsia bacterium would survive,” he says.

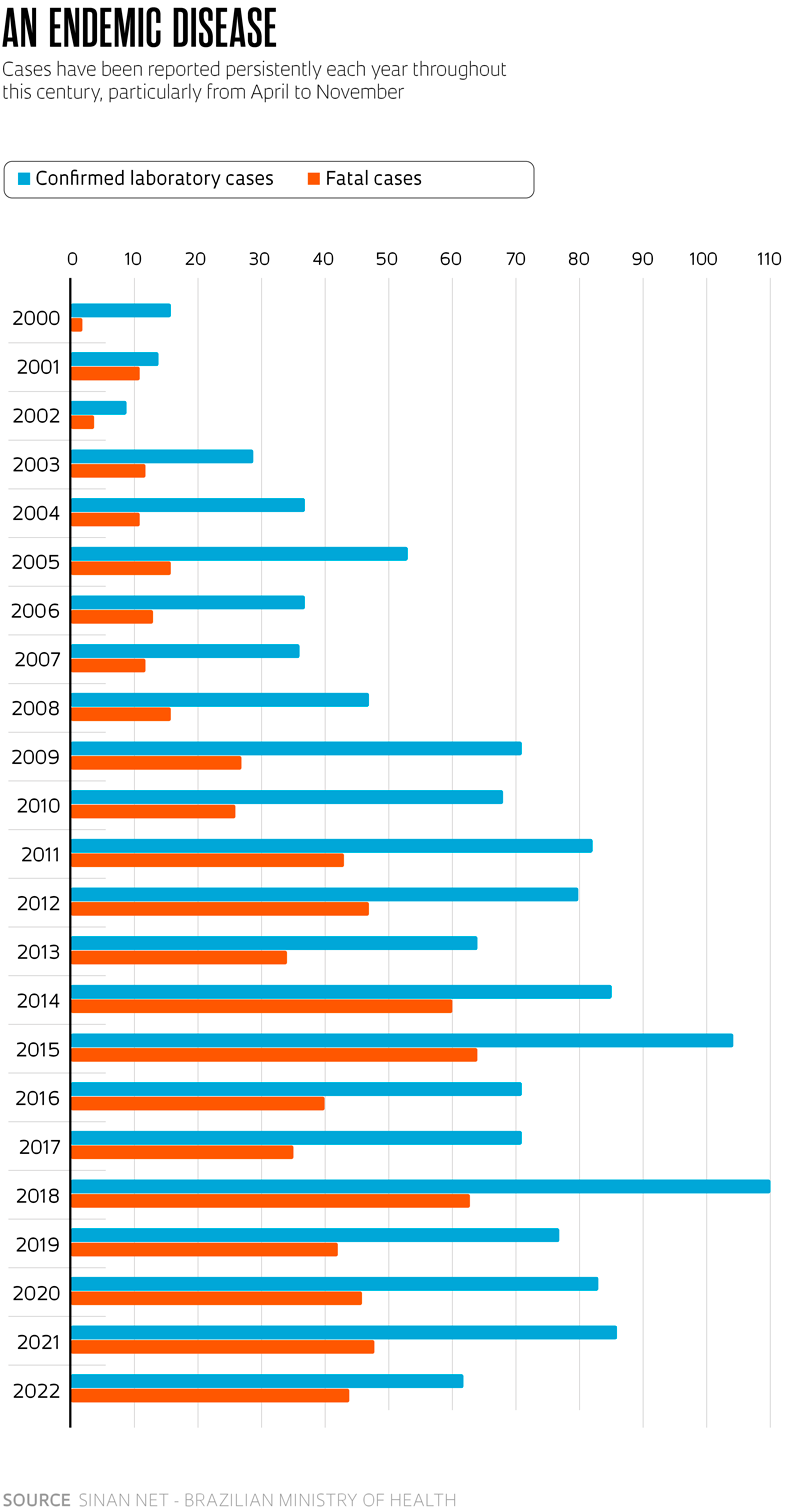

A specialist in ecological studies in human-altered landscapes, Verdade has dealt with situations throughout his career where human contact with wildlife leads to disease transmission. Brazilian spotted fever had vanished from the municipality of Piracicaba, where CENA is located, for several decades during the latter half of the twentieth century. It was Verdade’s research group that rediscovered it in 2001.