“Everyone agrees that the Universe is expanding rapidly. But why? We still don’t know,” says the astrophysicistEDUARDO CESAR

Astrophysicst Brian Schmidt, who was born in the U.S. state of Montana, raised in Alaska and has been based at Australian National University since 1996, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011 at the age of 44. He shared the prize with colleagues Saul Perlmutter of the University of California at Berkeley and Adam G. Riess of Johns Hopkins University and the Space Telescope Science Institute, for research that unexpectedly showed that the expansion of the Universe is accelerating. In the late 1990s, Schmidt and the other Laureates began observing distant stars of a certain category—Type Ia supernovae—that are created by the explosion of white dwarfs—very old, compact stars. The movements of this type of supernova can be used to measure distances.

“In my view, it was highly improbable that we would win the Nobel,” says Schmidt, who was at the University of São Paulo (USP) in early February to take part in the Conference on Cosmology, Large Scale Structure and First Objects, organized by the Office of the Dean of Research at USP, “because we still do not really know what dark energy is.” In this interview, Schmidt talks about his work and, of course, the mysterious dark energy, which is thought to comprise 73% of the entire Cosmos and to be responsible for its increasingly rapid growth.

What was your reaction when you first saw that the data indicated an accelerated expansion of the Universe?

I thought we had made a mistake. After we verified that there were no mistakes, I became concerned with the possibility that something unknown to us was happening. The Universe could be accelerating, or we and all the other scientists in this field might not have noticed an effect of some kind. I had to wait. Then we published a paper and, in 2000, other measurements corroborated our data.

Did you expect to win the Nobel?

There is always a lot of speculation about the prize. But in my view, it was highly improbable that we would win the Nobel.

Why?

Because we still do not really understand what dark energy is. Everyone agrees that the Universe is expanding rapidly. But why? We still don’t know. I thought they would wait [to award the Nobel] until we knew what dark energy is. But we may be dead when that happens. I’d say that we’ll probably be dead. I can think of many reasons for them not to award the prize. It was a big surprise.

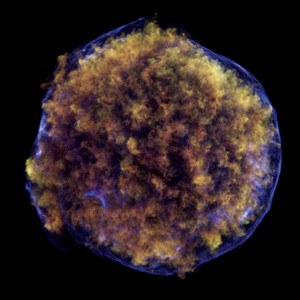

Type Ia supernova: Observations of this type of star showed accelerated expansion of the CosmosNASA/CXC/JPL-CALTECH/CALAR ALTO O. KRAUSE

Is dark energy really the most mysterious thing in the Universe?

The Universe appears to be composed of 73% dark energy, which appears to be part of space and to be causing the Universe to expand. In order to understand dark energy, we need to understand why it is part of the Universe. So far nobody has a reasonable explanation for this. There are many, but no one explanation is better than the next. It’s a scientific maze. Dark matter, which is 23% of the Universe, may very well be a particle that we have not yet encountered. If it’s a particle that we can discover in an accelerator such as the LHC, everything fits together. Nothing needs to change. Everything will be reasonably simple. That may not be the solution, but for now it appears to be a reasonable explanation for dark matter. In the case of dark energy, we still do not have a clear indication. Fifteen years ago we didn’t know we were failing to see 96% of the Universe [the galaxies, stars and planets account for only 4% of the Cosmos].

Will ongoing observance of supernovae help you discover the nature of dark energy?

Since 1998 we’ve been observing thousands of objects and we always have the same answer, but with a little more precision. But we are reaching a point where it will be difficult to keep making progress. Supernovae are not perfect. We are beginning to see that they have defects when it comes to measuring distances. We’re reaching a point where we will have to find other methods for measuring dark energy.

Is it a problem of method or of lack of technology?

The problem is not technology. When we measure distances, we use these stars that explode as if they were obeying laws. But to a certain extent they are not obeying any laws. They are very complicated and they have a certain lack of precision. It’s like predicting the weather. There’s a limit to how well we can predict the weather. There is randomness in the Universe. It is possible to measure the distance of supernovae up to a certain degree, regardless of the method we are using. But we are reaching the limit of those measurements.

What is the main research project at the present time?

It’s the SkyMapper, a relatively modest 1.35-meter telescope [located on the outskirts of Sydney], which is mapping the entire southern-hemisphere sky. We are mapping the stars six times in six different colors. This means we will have 36 images of each piece of sky. It will be a digital map, and the colors will enable us to observe what is in each piece. We will be able to tell, for example, the distance, temperature and chemical composition of each star. We hope to find interesting objects that can be studied in detail by larger telescopes, and thereby discover, for example, how the first stars in the Milky Way and the Universe were formed.

Why did you decide to be an astronomer?

I always thought I would be a meteorologist. I worked at a meteorological station in Alaska. But I felt that the work wasn’t very interesting. Then I thought about astronomy. I thought I’d never get a job in that field, but I decided to study it anyway. I knew that by studying astronomy, I would learn physics, computers and many other skills and that I would end up finding some kind of job. I was surprised when I got a job in astronomy after graduation. It was great.

How did you begin studying the question of the expanding Universe?

It was a piece of science that interested me deep down. How old is the Universe? What will be its destiny? It was a very uncertain thing. I was lucky to be living at a time when the question was interesting, the answers were unknown and technological changes enabled us to attempt to answer those questions. It was a fortuitous thing.