The expansion of agriculture, livestock farming, and deforestation has had drastic impacts on the Caatinga, a semiarid scrubland biome in northeastern Brazil. Cropland and pastures, some abandoned and others still in use, cover 89% of the Caatinga—the only biome that is entirely in Brazil, spread across 10 states. Only 11% of its area remains covered by vegetation typical of northeastern Brazil, which would have been abundant under the same climate and soil conditions before human occupation, according to an article published in the journal Scientific Reports in October by biologists from the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB) and the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE).

“The Caatinga seems able to resist climate change and higher temperatures, but not human activity,” points out UFPB biologist Helder Araujo, lead author of the study. Araujo and his colleagues reconstructed the area occupied by forest and shrub environments in the Caatinga over time using a method called potential species distribution modeling, based on variables such as present-day birds and now-extinct herbivorous mammals that lived in the region thousands of years ago.

The researchers then added information about current vegetation in the biome, sourced from nongovernmental organization MapBiomas, as well as climate data from the WorldClim platform and information on human alterations in the region published in the journal Scientific Data in August 2016. They analyzed the changes in 12,976 hexagons, each measuring 5 square kilometers (km²), to find which areas are still covered by forest and which are now covered by smaller vegetation. “Most of the area that could be occupied by forest is now covered by shrubs,” says Araujo.

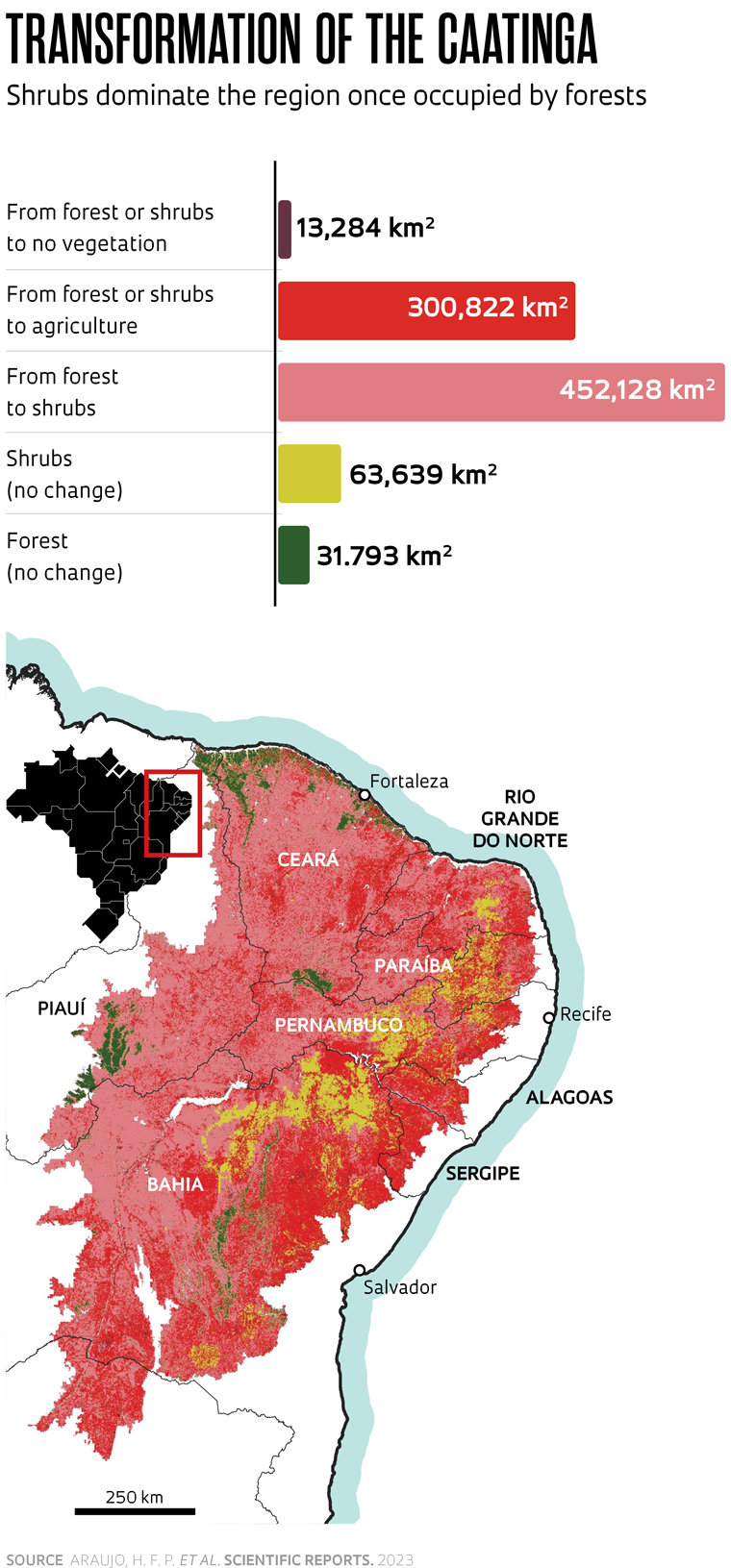

According to the study, of the 731,211 km² with the potential for forest cover (equivalent to 84.6% of the biome’s total area), only 31,793 km² (4%) was occupied by forest (see map). Shrubland has expanded by 390% into closed and denser forests.

“Other studies consider modified areas to be native vegetation, which it is, since they are still plants from the region, but there is a degree of environmental degradation because they were or are modified by agriculture,” says Araujo. “Secondary vegetation cannot become forest again, even after decades.” Furthermore, the researcher stresses, because of greater exposure to the Sun, there will be less water in the soil where the vegetation is smaller.

Using different methodologies, Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change calculated that 53% of the Caatinga remains, while nongovernmental organization MapBiomas estimates the figure at 47%. In its most recent maps from 2022, MapBiomas found that agricultural land, introduced in the region in the sixteenth century, was still expanding, now accounting for 35% of the Caatinga. The value is the same as found by the study published in Scientific Reports, which also reported that 1.6% of the biome had no vegetation, because it is either inhabited by humans or undergoing desertification.

“With satellite images, we can accurately map the areas used for agriculture, which have well-defined boundaries, but pastures can be confused with natural non-forest areas: the herbaceous Caatinga,” explains Washington Rocha of the State University of Feira de Santana (UEFS), head of MapBiomas Caatinga. “The current method is good at mapping parts of the Caatinga covered by trees and shrubs, but it does not allow us to accurately distinguish natural areas from areas with regenerated or restored vegetation.”

Helder F. P. Araujo

Guava trees and native vegetation in the Cariri region of Paraíba

Helder F. P. AraujoMarcelo Tabarelli and Inara Leal, both ecologists at UFPE, identified that clearing native forests for crops or livestock increases the number of leafcutter ant nests, which can reach up to 3 meters (m) deep, hindering the regrowth of vegetation when the area is abandoned.

Restoration

Araujo, Tabarelli, and researchers from other institutions are examining the options for restoring native vegetation. Other studies by the group, published in the journals Land Use Policy and Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, indicated that the soil moisture loss so common in degraded areas could be prevented if native forests occupied 50% of rural properties. According to these studies, areas with more native vegetation than the 20% required by law are more productive, especially during dry years.

Promising field experiments by Gislene Ganade, an ecologist from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, showed a survival rate of over 80% among seedlings grown in nurseries and transferred to the wild when the roots reach 1 m in depth.

“Restoration and well-executed cultivation could reverse the degradation and poverty currently faced in the Caatinga,” concludes Araujo. In 2020, the Nexus Caatinga program, run by Araujo, published a booklet containing suggestions on water conservation, such as crop rotation and integration of crops and livestock.

Scientific articles

ARAUJO, H. F. P. et al. Human disturbance is the major driver of vegetation changes in the Caatinga dry forest region. Scientific Reports. Vol. 13, 18440. Oct. 27, 2023.

ARAUJO, H. F. P. et al. Vegetation productivity under climate change depends on landscape complexity in tropical drylands. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. Vol. 27, no. 54. Sept. 2022.

ARAUJO, H. F. P. et al. A sustainable agricultural landscape model for tropical drylands. Land Use Policy. Vol. 100, 104913. Jan. 2021.

VENTER, O. et al. Global terrestrial human footprint maps for 1993 and 2009. Scientific Data. Vol. 3, 160067. Aug. 23, 2016.

Books

ARAUJO, H. F. P. Nexus – Água, energia e alimento na região mais seca do Brasil: Informativo prático sobre princípios de paisagens agrícolas sustentáveis. Areias, PB. 2020.

MAPBIOMAS. Destaques do mapeamento anual da cobertura e uso da terra no Brasil de 1,985 a 2,021 – Caatinga. Oct. 2022.

Republish