DANIEL SCHWEN/WIKIMEDIA

Analysis of graphite rocks like these help reconstruct the formation and fragmentation of supercontinentsDANIEL SCHWEN/WIKIMEDIAIn 2016, during an expedition to northern China, geologist Wilson Teixeira, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Geosciences (IGC-USP), noted a similarity between the graphite-rich rocks of the Jiao-Liao-Ji region and those in the Brazilian municipality of Itapecerica, Minas Gerais. Upon returning to Brazil, he and four other geologists were able to confirm his conclusion. The Brazilian and Chinese graphite deposits were formed about 2 billion years ago during the Proterozoic geological era, when advanced single-cell organisms were emerging. Detailed in an article published in Precambrian Research in May, the age of the graphite and the characteristics of the rock in which it is embedded led the researchers to propose that the Itapecerica and Jiao-Liao-Ji regions, now separated by almost 17,000 kilometers, were once neighbors in the distant past, when together they formed part of one of Earth’s ancient supercontinents, known as Columbia.

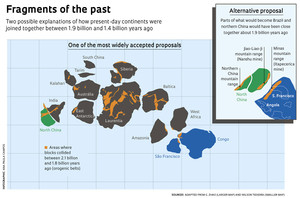

Geologists estimate that Columbia was formed between 1.9 billion and 1.8 billion years ago, through the collision of landmasses that now compose the present-day continents. The supercontinent existed until about 1.4 billion years ago, when it began to fragment due to the movement of tectonic plates, the immense blocks that make up the planet‘s outermost rock layer.

In the Precambrian Research article, Teixeira and geologists Maria Helena Hollanda, from USP, Elson Paiva Oliveira, from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Elton Luis Dantas, from the University of Brasilia (UNB), and Peng Peng, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, propose that in the remote past, parts of the states of Minas Gerais and Bahia in Brazil and the Congo region of western Africa could have been welded with northern China as part of the Columbia supercontinent.

The main evidence for this union is the ages of the graphite-rich rocks and the geological conditions under which they were created in Minas Gerais and China. “This mineral is formed under high temperatures and pressure, and is therefore a sign of regions where huge collisions occurred between ancient continents,” explains Teixeira. According to him, the fact that the Brazilian and Chinese graphite is similar in age indicates that they originated from collision processes that occurred at the same time or very close together in time. Brazil is home to 27% of the world’s graphite reserves, and China to 56%.

Teixeira believes that if what is now part of South America really was a close neighbor of present-day northern China 1.9 billion years ago, then areas of what would later become Africa were almost certainly present in the region too. In recent decades, growing evidence has suggested that Minas Gerais and Bahia were once united with the African continent, forming a geologically stable structure called the São Francisco-Congo craton.

Teixeira believes that if what is now part of South America really was a close neighbor of present-day northern China 1.9 billion years ago, then areas of what would later become Africa were almost certainly present in the region too. In recent decades, growing evidence has suggested that Minas Gerais and Bahia were once united with the African continent, forming a geologically stable structure called the São Francisco-Congo craton.

“There is a lot of debate about Columbia’s configuration,” says geophysicist Manoel D’Agrella, a professor at USP’s Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences (IAG-USP) and a specialist in paleomagnetism, a field of geophysics that studies the intensity and direction of the Earth’s magnetic field recorded in rocks—the magnetic information recorded within them reveals their location on the planet at the time they were formed. In recent years, D’Agrella and his team have attempted to establish the successive positions that the northern region of South America, called the Amazonian craton, would have occupied during Columbia’s existence, as detailed in a 2016 article in the Brazilian Journal of Geology. He recently began analyzing rocks from Minas Gerais to see if their magnetic characteristics correspond to the positions of the São Francisco-Congo and northern China cratons suggested by Teixeira and his group. Many models that attempt to explain where the current continents were positioned in Columbia do not place the São Francisco-Congo formation near northern China, which is often attached to what corresponds to present-day Australia.

Columbia’s existence was first proposed in 2002 by geologists John Rogers, from the University of North Carolina, USA, and Madhava Santosh, from the University of Geosciences in Beijing, China, based on similarities between the rock formations in India and the Columbia River region of the US state of Washington. When Columbia broke up around 1.1 billion years ago, its fragments were rearranged, forming the supercontinent Rodinia, which later also fragmented. From the fragments of Rodinia came Laurasia, formed by North America, Greenland, Europe, and the north of Asia; and Gondwana, which was composed of South America, Africa, Australia, India, Antarctica, and Madagascar. With the continued movement of the tectonic plates, which move away from or toward each other at speeds of up to 10 centimeters per year, geologists predict that a new supercontinent called Amasia may form in the next 250 million years, resulting from a collision of North America and Asia.

Projects

1. Evolution of Archaean landmasses in the São Francisco Craton and Borborema Province: Implications for global geodynamic and paleoenvironmental processes (No. 12/15824-6); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Elson Paiva de Oliveira (UNICAMP); Investment R$3,696,059.08.

2. Tectonic characteristics of the Rio das Mortes, Nazarene, and Pores de Campo greenstone belts: Implications for the crustal evolution of the Mineiro belt (No. 9/53818-5); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Wilson Teixeira (USP); Investment R$357,590.53.

Scientific articles

TEIXEIRA, W. et al. U-Pb geochronology of the 2.0 Ga Itapecerica graphite-rich supracrustal succession in the São Francisco Craton: Tectonic matches with the North China craton and paleogeographic inferences. Precambrian Research. V. 293, p. 91–111. May 2017.

D’AGRELLA FILHO, M. et al. Paleomagnetism of the Amazon craton and its role in paleocontinents. Brazilian Journal of Geology. V. 46, No. 2, p. 275–99. 2016.