Rafael Rocha / EMBRAPAAmazon robusta coffee, a variety developed by EMBRAPA and adapted to the northern Brazilian climateRafael Rocha / EMBRAPA

In 10 or 20 years’ time, if new types of coffee plantations do not take the place of current ones, coffee produced in Brazil may be more bitter, acidic, and astringent. That’s the conclusion reached from tests conducted at the Environmental Research Institute (IPA) of São Paulo, in chambers simulating the climate over the coming decades, with more carbon gas (CO₂) in the atmosphere and less water in the soil than found today. “With more CO₂, coffee plants may photosynthesize more and grow higher, but possibly they will produce fewer fruits,” considers Douglas Domingues, of the University of São Paulo (USP), who participated in the experiments described in the scientific journal Plants in July 2022.

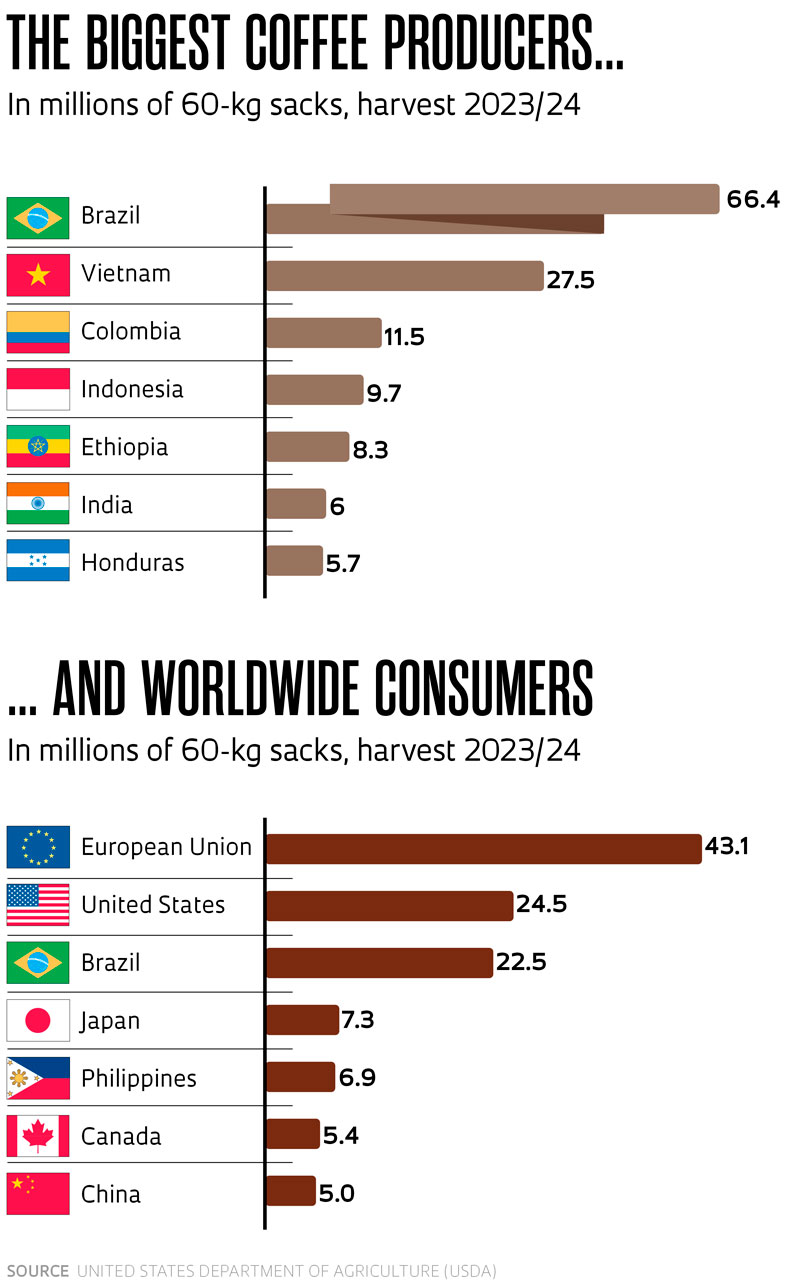

The idea that other regions will be used for planting is also plausible; the biggest current producers are the states of Minas Gerais, with almost half of Brazilian output, followed by Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Bahia, Rondônia, and Paraná. Canephora can withstand higher temperatures, whereas arabica is more sensitive.

According to simulations run by researchers from the Federal University of Itajubá (UNIFEI) in Minas Gerais, detailed in Science of the Total Environment in January, between 35% and 75% of lands currently occupied by coffee plantations could become unsuitable due to climate change by the end of the century, driving the quest for higher, colder areas.

Studies conducted by the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) indicate that coffee-growing areas may shrink and become restricted to the highest environs in the southeast, while also being implemented in the Brazilian South, including the state of Rio Grande do Sul, where coffee is only consumed and not grown at present (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 198).

“We need to alert farmers about how to protect their crops from the effects of climate change,” says agricultural engineer Celso Vegro, of the Institute of Agricultural Economics in São Paulo. One of the methods he has looked at is rural insurance, which covers losses arising primarily from climatic phenomena. Vegro found that fewer than 15,000 of the almost 200,000 rural producers in São Paulo State have adopted this mechanism to guard against failed harvests.

Almost three centuries of history in Brazil

After its discovery in Africa — arabica in Ethiopia, conilon in Congo, and robusta in Guinea — coffee made its mark in Europe and its South American territories. In 1727, at the behest of the Portuguese government, officer Francisco de Mello Palheta (1670-1750) smuggled from Guyana, then a French colony, the first seedlings to the city of Belém, part of what was then known as the state of Maranhão and Grand-Pará.

“Apparently there was much interest in the crop [coffee], as in 1734 the Port of Lisboa Customs reported the disembarkation of 3,000 arrobas (today in Brazil 1 arroba = 15 kilograms) of coffee from the General Company of Maranhão and Grand-Pará,” observes Vegro in a January 2023 article in the Revista de Economia Agrícola (Agricultural economics journal).

In the years that followed, plantations expanded across the Brazilian Northeast and then southward, arriving around 1820 in the Paraíba Valley between the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Cantagalo and Vassouras, in Rio, and Areias and Bananal, in São Paulo, became prominent producers during this period, until falling into decline at the end of the nineteenth century due to soil exhaustion and scarcity of labor with the end of the slavery system.