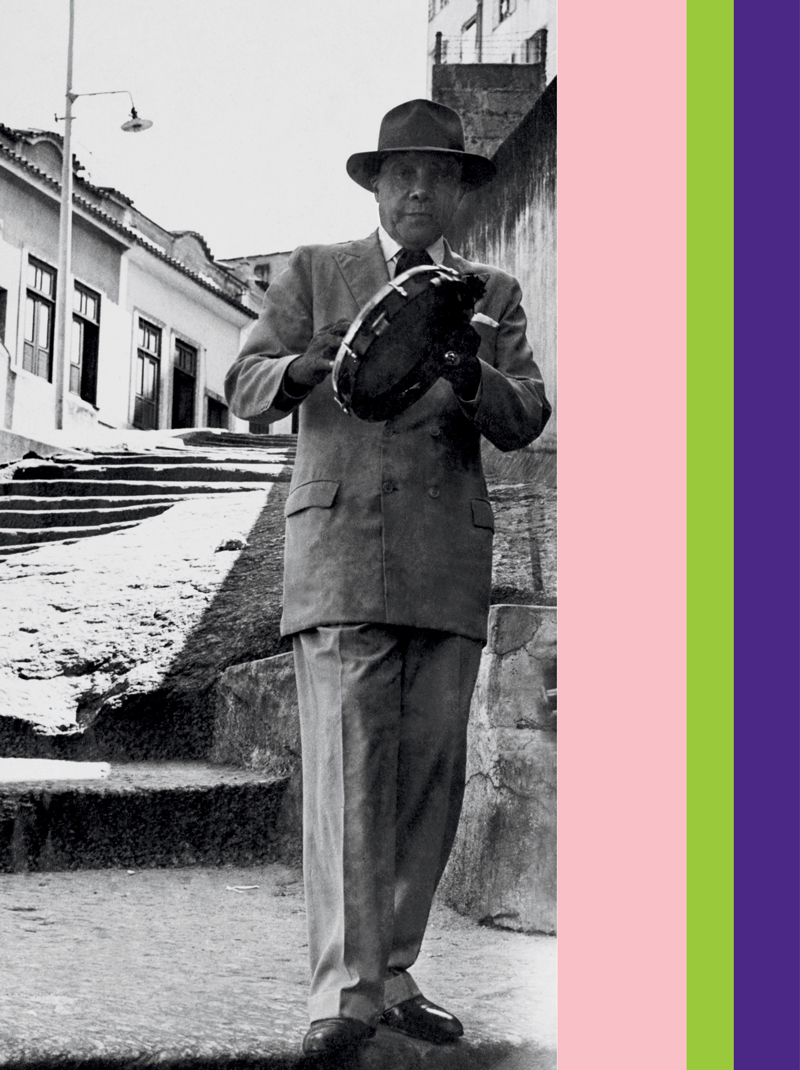

João da Baiana (1940–1950) / Unidentified Photographer / Almirante collection / FMIS-RJ Archive1940s/50s Rio de Janeiro—samba musician João da Baiana, with his pandeiro tambourine: the instrument was the target of police persecution in the early 20th centuryJoão da Baiana (1940–1950) / Unidentified Photographer / Almirante collection / FMIS-RJ Archive

When a group gathers around master griot (African storyteller) Ana do Coco, in the Novo Quilombo roda de coco circle in the town of Conde, Paraíba State, the music played has multiple influences. The sound, the dancing, and the singing hark back to African, Indigenous, Arab, and European origins. This diversity of references can also be seen in Brazil’s far north: in Roraima State—population 640,000—civic events and jazz festivals present sounds born of the encounter between Caribbean rhythms, Amerindian singing, and even gaucho (southern South American) traditions. In samba, the pandeiro, considered a national symbol, portrays a tortuous history of racial conflict and populist nationalism with its rhythm.

These are some of the accounts in the collection Histórias das músicas no Brasil (Histories of musics in Brazil), comprising five books—each covering a different region of the country. Edited by the Brazilian Association of Research and Postgraduation in Music (ANPPOM), the series is available for free download on the institution’s website. By pluralizing both “history” and “music,” the collection highlights the myriad influences that determine how music is made in a continental and multiracial country such as Brazil.

Arranged by musicologists Marcos Holler, of the State University of Santa Catarina (UDESC), and Mónica Vermes, of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES), the project seeks to showcase modern academic output. “One of our aims was to demonstrate how the history of music has been enriched by closer interaction not only with ethnomusicology, but also with sociology and anthropology,” says Vermes, ANPPOM’s director of publications.

“There is much research ongoing in Brazil, but we have noticed that its publication is often restricted to the region of its production,” adds Holler. “To this end we chose to divide the publication into five volumes, with well-defined regional focus.”

This area of study has been growing in Brazil since the 1980s—ANPPOM itself was founded in 1988. This century the trend has gained pace, moving with the expansion of universities across the country, according to musician and historian André Acastro Egg, of the State University of Paraná (UNESPAR) and the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), who, along with UDESC historian Márcia Ramos de Oliveira, coedited the volume dedicated to Brazil’s southern region. This growth has brought with it a thematic diversification which, in addition to analysis of musical practice and sounds, incorporated the study of social, political, ethnic, economic, and gender aspects.

Throughout the twentieth century, music studies in Brazil concentrated excessively on development of the classical genre, according to Egg. “In the singular, the expression ‘history of music’ refers to a nineteenth-century positivism inheritance mindset, which largely undertakes studies focused on composers and works—primarily classics,” says the researcher. “The end of the twentieth century saw a methodological revamp: thinking about Brazil’s music in terms of wider historical accounts.”

According to musicologist and historian Ana Guiomar Rêgo Souza, of the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), only in the last 20 years has music history research truly opened up to the plurality of its manifestations, beyond the European framework. “It is obviously not possible to exclude the European origins of Brazilian music—Portuguese in particular—up to the beginnings of the nineteenth century. Our goal, however, is to demonstrate how it has always been in contact with other manifestations,” explains Souza, who, together with educator Flavia Maria Cruvinel, also of UFG, arranged the volume covering Brazil’s Central-West region.

According to Holler, academic music history content production was very much driven by digital technology. The most widely referenced source in this area is the Brazilian National Library’s Digital Collection, which since 2012 has provided online access to Brazilian journals published from 1808, except those still in circulation. This extensive archive offers news on musical presentations, recordings and tours, critiques and chronicles, along with advertisement of instruments, records, and concert halls.

Milena MedeirosMembers of the coco circle group Novo Quilombo of Paraíba StateMilena Medeiros

In their foreward to the volume on the Brazilian Southeast, historians Virgínia de Almeida Bessa, of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and Juliana Pérez González, an independent researcher, state that the twentieth century also bore witness to the trend of seeking out a national musicality, in other words the “Brazilianism” of this artistic embodiment. But how to expound on a singular national music style in a continental country?

Percussionist and musicologist Eduardo Vidili, of UDESC, addressed this question through his article in the same volume. The researcher observes that different songs considered as the quintessence of Brazilianism have the pandeiro as a national symbol: a good example would be Aquarela do Brasil, by Ary Barroso (1903–1964), with the verse “land of samba and pandeiro,” and Assis Valente’s (1911–1958) Brasil pandeiro, whose title directly carries the association.

Yet this small percussion instrument came to be persecuted by the police in the early twentieth century: associated to vagrancy, it could land Samba musicians in jail. Musicians admired in modern times, such as João da Baiana (1887–1974), later gave interviews about the repression they suffered. By the 1930s, however, the pandeiro “was revered with great pride as something that represented us as a nation,” says Vidili. This rapid transition is explained by circumstances such as the interaction between carnival groups and journalists, the portability of the instrument, and the efforts of the Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954) government between 1930 and 1945, to develop cultural nationalism in Brazil.

“The ascension of the radio was the decisive factor in consolidating the pandeiro in the national imagination,” Vidili says. In 1932, Vargas regulated the exploration of radio publicity, enabling commercial broadcast stations to be structured, notably Mayrink Veiga in Rio de Janeiro. “A versatile instrument, the pandeiro was a good fit for radio productions, in which hired musical ensembles played live. It was here that batucada (an Afro-Brazilian, percussion-based substyle of samba) underwent a type of domestication. At the same time, radio pandeiro players started to get press coverage,” continues the musicologist.

According to Vidili, this period gave rise to a growing musical formation common to date in the context of choro: the so-called regional, whose sole percussion instrument is the pandeiro. “This happens for the same reason that brought it into the streets, where the police persecution took place: it is portable, produces varied sounds, and has a low-level range in terms of volume, but adapts to the trio of acoustic guitar, cavaquinho (a small, ukelele-type guitar), and flute.”

In the chapter “The ‘opera’ in Pirenópolis since the 1800s,” written in partnership with philosopher Geraldo Márcio da Silva, of the Goiás State Education Department, UFG’s Souza demonstrates the musical theater of the city of Pirenópolis (Goiás State) with forms of sociability and local power structures, primarily in the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. The word “opera” falls within quotation marks because in those days this term described any musical presentation.

At the heart of musical sociability in the region were the Divino Espírito Santo (Divine Holy Spirit) festivals, with locals gathering around bands playing in the open air, principally with brass instruments. These same bands played in theaters, with stringed instruments added, making them somewhat similar to symphony orchestras. “These events were very significant institutions at each venue, practically an identity model,” says Souza.

In this respect the bands played a fundamental role, according to the historian and musicologist. The ensembles had differing origins: they were formed in churches, military and police institutions, but also by private initiative. One example would be the band Phoenix, founded in the nineteenth century in Pirenópolis by musician Joaquim Propício de Pina (1867–1943), which is still playing today. “The bands dominated the Brazilian music scene in the second half of the nineteenth century, in a time with no television or radio. It is not possible to imagine a festivity without a band in this period, because orchestras were the things of larger cities, and even then, were few and far between.” The theme of these bands and festivals features in several articles in the volume on the Central-West.

Arquivo da Banda Phoenix 3 Reproduction / Facebook / Trio RoraimeiraTop: Phoenix, from Pirenópolis (Goiás State), in the 1940s; and bottom: Trio Roraimeira, in 2017, an exponent of the northern Brazilian musical movementArquivo da Banda Phoenix 3 Reproduction / Facebook / Trio Roraimeira

Souza adds that an important discovery of recent studies revealed the role of women in musical sociability in the region. “High society gathered during soirées, essentially organized by women. They played and sang even more frequently than the men,” she adds. Women had the role of organization and command, including of music played in cathedrals. “However, when priests came visiting from the Vatican, the women took a step back and discreetly distanced themselves from this function.”

In the volume on the Brazilian Northeast, ethnomusicologists Eurides Santos, of the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), and Erivan Silva, of the Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), open their article by affirming that, as with other manifestations, “the cocos are, at the same time, a musical genre and a popular event involving music, dance, and poetry.” Based on the unification of sounds, sociability, and race relations, the authors analyze the presence and significance of this practice, characterized by singing in the form of questions and answers, accompanied by hand-clapping and dancing in a circle.

Afro-Brazilian in origin, coco spread through the rural and urban areas of states such as Alagoas, Pernambuco, and Paraíba, going hand-in-hand with the diaspora of the Black population. It is still practised in many quilombos (maroon settlements). Adopted by Indigenous communities in ceremonies such as the Toré and the Jurema worship, it became “a symbol of resistance and a symbolic Afro-Indigenous capital across much of the Northeast,” says Santos, of UFPB. Anthropological reports used in the demarcation of Indigenous or Quilombola lands point to the coco circle as a sign of former land occupation.

In Brazil’s North, the combination between the historical process and diversity of sounds is manifested in a condensed way in Roraima, according to musicologist Gustavo Frosi Benetti and musical educator Jefferson Tiago de Souza Mendes da Silva, both of the Federal University of Maranhão (UFMA). As they write in a chapter of the volume on this region, the population of Roraima has a diverse profile, reflecting the successive waves of occupation in Amazonia fomented by the Brazilian government: from the farms of the late nineteenth century to migration stimulated by the military regime (1964–1985). More recently, the advancement of farming frontiers, informal mining, and the arrival of Venezuelan immigrants have also expanded the demographic range of Roraima, and as a result the state is home to a wide variety of sounds. The researchers documented styles practiced in state capital Boa Vista and in 14 other municipalities. They uncovered material ranging from songs of Indigenous origin, first recorded by German anthropologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg (1872–1924) between 1911 and 1913, to the Caribbean reggae coming from Guiana. In towns such as São João da Baliza and Amajari, the significant populational presence from the Northeast makes the June festivals very popular. In Maranhão’s state capital São Luiz, gaucho migrants have, since the 1990s, held typically southern festivities, such as the Semana Farroupilha and Vaquejada.

“Reggae, which arrived in Boa Vista, capital of Roraima State, via the town of Bonfim, bordering the Guianese city Lethem, had a particular sound, different from that which we would associate to Bob Marley [1945–1981] and other famous names from original reggae, which emerged in Jamaica,” adds Silva. “Thus, the region saw the formation of a musical melting pot, blending Carimbó from Pará State, Caribbean elements from Venezuela, and other references. This fusion of sounds can frequently be heard on occasions such as the Tepequém Jazz Festival.”

One of the decisive moments for formation of the region’s sound was the 1980s, when, through music festivals and gatherings of composers, the Movimento Roraimeira emerged. “This phenomenon has been studied significantly in the state. It was strongly underpinned by composer-based production and had the perspective of creating a regional identity through the arts generally, and not music alone. Names such as Eliakin Rufino, Neuber Uchôa, and Zeca Preto were noteworthy in the period, and their compositions portray a variety of bases, whether European, first-nation peoples, or Afro-Latin cultures,” concludes Benetti.

Book

HOLLER, M. & VERMES, M. (editors.). Histórias das músicas no Brasil (5 volumes). Vitória-ES: National Association for Research and Graduate Studies in (ANPPOM), 2023.