An international consortium of researchers is collating comparative data from 16 countries across four continents on gender inequalities in the science, technology, and innovation (STI) environment, and has been sharing strategies and good practices to tackle the problem and mitigate its effects. Run by a group from the Madrid Polytechnic University (UPM) in Spain, the Gender STI project commenced in 2020 and has produced diagnoses confirming the scarcity of female agency in science, technology, mathematics, and engineering (STEM) careers across several countries, demonstrating the difficulties faced by women in achieving upper-echelon posts in research institutions and in leadership of international collaborations.

The network scrutinized the content of 528 STI cooperation agreements signed between 1961 and 2021, involving institutions or governments from two or more nations. It was found that only 15% of these mentioned gender issues or demonstrated concern about equality in supported research projects. Without doubt, this outlook has been improving over recent years. The data show that, from 2015, this type of reference was increasingly observed, albeit unequally in countries analyzed. Nations such as Canada, India, and South Africa stand out for their incorporation of clauses favorable to the inclusion of women in research projects or the direct participation of female delegates in diplomatic negotiations resulting in cooperation agreements. In Europe, Spain and Finland also stand out — almost 30% of signed agreements made some mention of gender equality.

However, agreements signed by Brazil, Argentina, and Portugal contained very little gender-related content. By way of example, 11 multilateral agreements involving science and technology organizations were analyzed, with none found to have made any such reference. Of some 33 agreements signed by support agencies in Brazil, only 5% mentioned gender aspects. Analysis of the data collected was supplemented by the results of a questionnaire applied to 204 people, and of 80 interviews with researchers and leaders across the countries making up the consortium.

One of the initial focus points of Gender STI was so-called scientific diplomacy, which is the use of science as an arm of foreign policy. Europe’s flagship scientific program Horizon 2020, which received investments of €80 billion between 2014 and 2020, made it one of its priorities to support projects promoting gender equality in universities and organizations in the European bloc, particularly encouraging change in institutional structures, and in the manner of funding them. As such European Union (EU) initiatives always carry an element of cooperation between countries in and outside the bloc, the need was identified to analyze any differences in dealing with gender disparities between partners, and to seek common strategies to tackle the issue. “Europe is a pioneer in this area. The inclusion of women in teams negotiating international agreements is compulsory in the European Union,” explains political scientist Janina Onuki, of the University of São Paulo’s School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH-USP), and its Institute of Advanced Studies (IEA). Onuki heads up Brazil’s participation in the consortium through a thematic project funded by FAPESP since 2020, within the scope of a cooperation agreement with the EU. On the European side, the network includes institutions from Spain, Finland, Italy, Austria, France, and Portugal, which engage with partners from countries across three other continents: Canada, the US, Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, South Africa, India, South Korea, and China.

Gender STI also collated available studies and statistics on gender disparities to compare the situation in the different countries. Female underrepresentation in science is a common issue for practically all of these nations. Data from 2022 indicate that less than 30% of researchers in member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — which total 38 countries among the most industrialized — are women. Although the interest of female students in STEM careers is on the increase, the growth rate is considerably low and it is not possible to project a balanced scenario in the near future.

Maternity and double-shifting means women take longer than men to conclude their doctorates in Brazil

Difficulties in obtaining leadership posts at scientific institutions is another palpable, unyielding reality. “I’m proud to work with a research group in which most of the leadership roles are occupied by women. But most of the meetings and activities I take part in, both in terms of European projects and scientific committees and conferences, are unbalanced in all aspects,” says María Fernanda Cabrera, a researcher from the Madrid Polytechnic University (UPM) and one of the coordinators of Gender STI, according to the university’s website.

Sociologist Alice Abreu, emeritus professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), comments that the discussion on gender equality in science is not new, but has shifted its focus in recent times. “Instead of seeing women as the primary issue and suggesting initiatives for them to obtain the necessary qualifications, there is now an understanding that diversity is paramount for scientific activity, and a shift in institutional structures is the only way of achieving gender equality in science,” she said in October last year during a conference in Madrid attended by Gender STI participants.

Data compiled on Brazilian academia includes a study conducted by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), according to which only 35.3% of the 16,048 research productivity grants offered in 2021 were aimed at women, with an even more marked difference in exact and earth science courses (just 22.1% of the scholarships for females), and engineering disciplines (23.3%). In human and biological sciences, the balance is very close, with 48.7% and 45.8% of grants for women, respectively. Productivity grants are a means of support that reward scientists demonstrating outstanding performance (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 311). Another important datum is the time that women take to conclude their doctorates, also according to CNPq: an average of 4.3 years to obtain the title, while men take 3.8 years. Maternity and “double-shifting” go towards explaining this phenomenon.

In one of the published studies, Janina Onuki and Gabriela Ferreira — the latter doing postdoctoral research in the thematic project — analyzed data from FAPESP and found that, in the foundation’s first six decades, women accounted for only 8% of its Board of Trustees members; currently a third of this board membership (12 members) is female. Board members are nominated by universities and scientific institutions, and by the state government, delegated by the governor for fixed terms. Mentions of gender aspects in the texts of international agreements signed by FAPESP were found in 2% of the documents analyzed.

At the end of 2022, the FAPESP Scientific Consultation arm gained a Program Office for matters related to Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI), with the remit of refining internal processes and removing obstacles associated to gender, ethnicity, or origin that hinder the development of talented, qualified researchers. “This kind of action is increasingly common around the globe, and is seen in practically all the countries studied,” says Onuki. “Many STI support agencies have set up committees or commissions within their decision-making structure to look at not just gender equality, but diversity in a more comprehensive manner.”

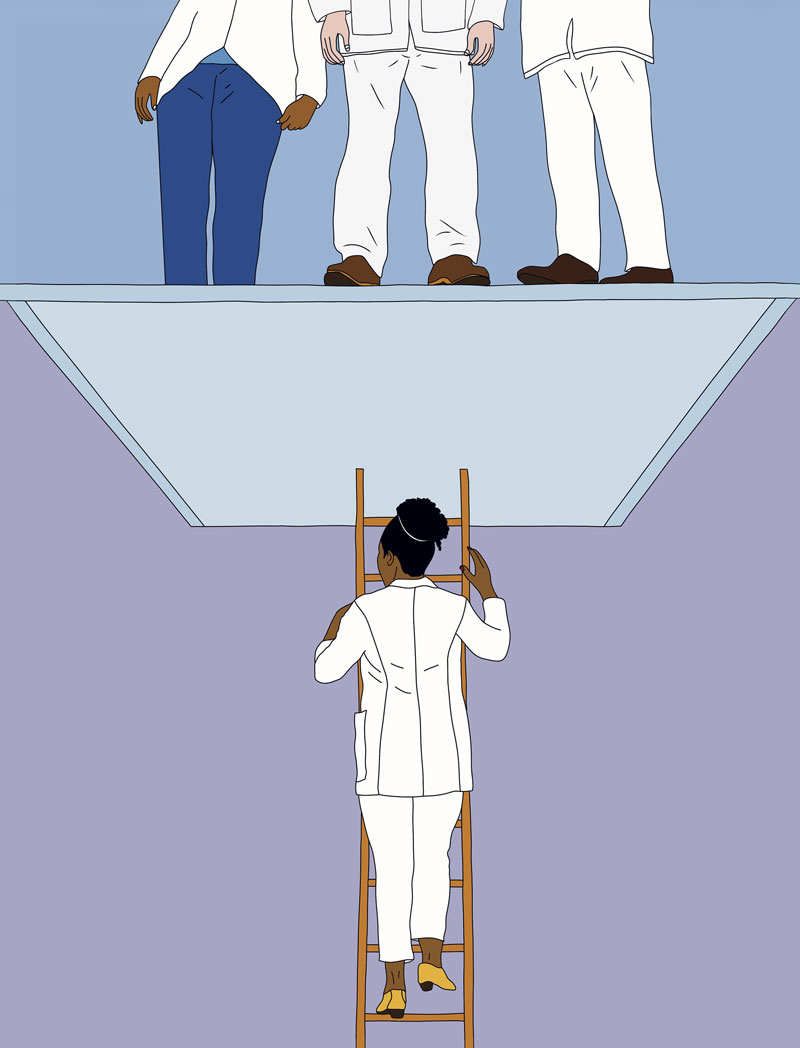

Mayara FerrãoGender STI is currently in its second phase, in which each participating country, now aware of its situation in comparison with the others, seeks to produce analyses and reflections on how to improve gender equality in a broader way. “The presence of women in both academia and diplomacy is increasing, but it is plain to see that they still face hindrances to career progression,” observes Onuki. “We want to understand why this happens, and we already know that you do not solve the issue by just extending opportunities.” There are also subjective components, she says. “There are situations in a career in which women simply do not compete with the men as they find the environment unfavorable, or that there is no return on their efforts,” states the political scientist, currently interviewing researchers in Brazil who have reached the top of the ladder to better understand these variables.

Mayara FerrãoGender STI is currently in its second phase, in which each participating country, now aware of its situation in comparison with the others, seeks to produce analyses and reflections on how to improve gender equality in a broader way. “The presence of women in both academia and diplomacy is increasing, but it is plain to see that they still face hindrances to career progression,” observes Onuki. “We want to understand why this happens, and we already know that you do not solve the issue by just extending opportunities.” There are also subjective components, she says. “There are situations in a career in which women simply do not compete with the men as they find the environment unfavorable, or that there is no return on their efforts,” states the political scientist, currently interviewing researchers in Brazil who have reached the top of the ladder to better understand these variables.

The consortium identified a set of good practices for promoting equality. In the case of bi- and multilateral scientific agreements, one example is the establishment of clauses and definition of gender equality goals in included projects and in the distribution of funds, and a requirement for females to be involved in negotiations between partners. The creation of gender advice units in scientific and academic organizations is also among the recommendations — there are such agencies in both the UN Commission on Science and Technology for Development (CSTD) and organizations of the scientific community, such as the International Union of Crystallography (IUCr).

Another example of good practice is the commitment to producing data and indicators separated by gender to help monitor and tackle disparities; in the 25th UN Conference on Climate Change, held in 2019 in Madrid, gender equality among the delegations was evaluated not only by the number of men and women present, but also by recording the amount of time for which representatives of the two genders could speak. The availability of mentoring programs, in which women counsel other women on their scientific careers, is one of the good practices — another method of mentoring is applied to decision-makers, to raise their awareness of the need to seek gender balance. Positive action policies across Brazilian universities are also mentioned among good practices, along with the efforts of an Argentine statistics NGO to provide gender-specific data.

A watch on the incidence of sexual harassment in the academic environment is also an emerging theme. Countries such as France and Ireland have launched initiatives to tackle gender violence in university and research institutions.

The knowledge produced by the consortium paved the way for the European Observatory on Gender in Science, Technology, and Innovation, which also works to connect initiatives across different institutions. “In the coming months we will inaugurate an observatory along the same lines here in Brazil with the studies conducted into the country’s situation,” says Janina Onuki.

Project

Gender in STI: Gender equality in science, technology, and innovation: Bilateral and multilateral dialogues (nº 20/07129-2); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Agreement European Union (Horizon 2020); Principal Investigator Janina Onuki (USP); Investment R$542,415.80.