“Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly, and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050, in line with the science.” This statement, the result of intense negotiations, was the key decision taken by almost 200 countries, including Brazil, at the most recent United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference (COP28). The agreement was announced on December 13 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, one of the 10 largest oil producers in the world, where the two-week meeting took place.

Achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 does not mean the countries have agreed to ban the use of oil, gas, or coal by the middle of this century, however. It is simply a declaration of principles that over the next 30 years, the nations must reduce greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible, with the aim of mitigating climate change caused by human activity.

In cases where a reduction is not possible—or as most skeptics would say, not desired—countries must adopt compensatory mechanisms that remove the same amount of gas from the atmosphere as is produced. However, carbon offset technologies, as they are known, are controversial. There is no scientific evidence that they are safe or effective on a large scale. The concept of net-zero emissions could therefore be nothing but a pipe dream.

“While we didn’t fully turn the page on the fossil fuel era here in Dubai, this is clearly the beginning of the end,” said Simon Stiel, executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in his speech at the end of the conference. “Now all governments and businesses need to turn these pledges into real-economy outcomes, without delay.”

It was the first time that a COP agreement explicitly cited fossil fuels as the primary cause of the climate crisis and addressed the need to gradually reduce their use and begin transitioning to cleaner sources of energy, such as wind and solar.

While cautiously in favor of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the agreement reached at the conference is extremely vague in terms of goals and deadlines, as well as being modest when it comes to funding for more sustainable and clean forms of energy consumption.

The final text agreed upon at COP28 states that the participant countries commit to tripling the use of renewable energy and doubling their energy efficiency by 2030. An international fund was created to mitigate the impacts of climate change, especially in poor countries. Its current value of US$700 million, however, represents less than 1% of the amount needed annually to carry out this task.

Reactions to the terms and content of COP28’s final text varied between two extremes, with a minority taking an intermediate position. There was euphoria among some signatories, who hailed it as a historic advance. But the wider public, including environmental groups and many scientists, described the document as disappointing. They had hoped that the conference would commit to an urgent ban on the use of fossil fuels, instead of promoting a generic transition.

“The announced transition is exactly what most countries have already been doing for more than 20 years, with the implementation of solar and wind energy, electrification of the transport sector, and other similar measures,” says Paulo Artaxo of the Institute of Physics at the University of São Paulo (IF-USP), one of the coordinators of the FAPESP Research Program on Global Climate Change (PFPMCG), who participated in the meeting in Dubai. “A recommendation to do something that is already being done cannot be characterized as progress.”

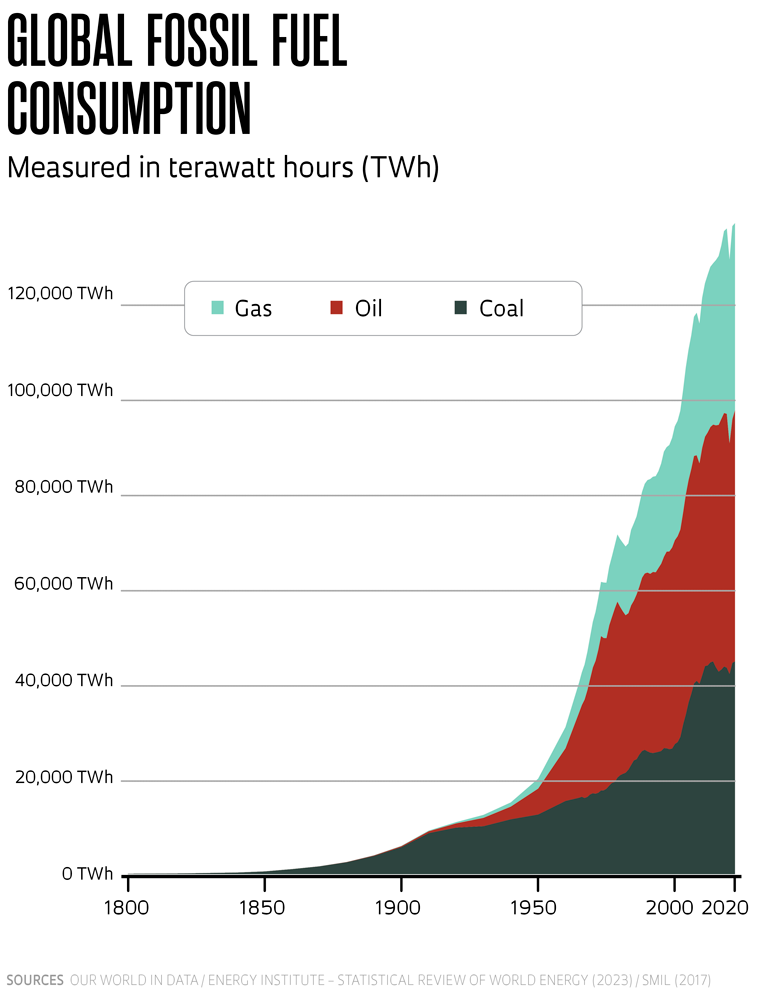

The proportion of the planet’s energy that comes from renewable sources has increased in recent decades, but fossil fuel consumption, which accounts for about 75% of greenhouse gas emissions, has risen in absolute terms year on year. The one notable exception to this trend was during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic (see graph on this page).

For Gilberto Januzzi of the Interdisciplinary Center for Energy Planning at the University of Campinas (NIPE-UNICAMP), the outcome of COP28 needs to be examined from two angles. One is that scientific information on the role of fossil fuels in climate change was ratified. The other relates to the establishment of concrete goals and policies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“Progress was made on the former, given the history of diplomatic negotiations on climate change,” points out Jannuzzi, who is also a PFPMCG coordinator. “Even the big oil producers have finally recognized the role fossil fuels play in global warming. I hope this scientific debate is over.”

He notes that in practical terms, the COP28 agreement is overdue and unsatisfactory. “It took us 30 years to reach this agreement,” emphasizes Jannuzzi. “But it does not go far enough to keep global warming within the maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius (ºC).”

According to the Paris Climate Accord, the world must strive to restrict global warming to less than 2 ºC above preindustrial (around 1850) levels within the coming decades. Ideally, the temperature rise would not exceed 1.5 ºC, a value that is considered high, but within which the resulting socioeconomic problems would remain potentially manageable.

The most recent estimates by the UN, however, put the world on track for an increase of 2.5 ºC if the current rate of greenhouse gas emissions continues. Unsurprisingly, 2023 was considered by far the hottest year recorded worldwide since the mid-nineteenth century.

Republish