When it was time for me to apply to college, I thought about studying physics. I really enjoyed the subject at school and I always liked applied mathematics too. I’m not particulary talented at dealing with pure abstractions and symbols, but I’ve always been interested in using mathematical tools to solve problems in areas such as physics, chemistry, and biology.

I spoke to my physics teacher at the time in search of guidance, but he discouraged me. He told me physics was much more complicated than what I had learned at school. Since he was unwilling to help me, I went to the library to read some physics books. I didn’t understand a thing. Nowadays I’m comfortable reading about physics, but at the time it seemed impenetrable and I gave up.

I was good at languages and I always really liked literature, so I started thinking about taking a language and literature course instead. My mother’s family came to Brazil from Eastern Europe — they spoke German and some Yiddish, and my grandmother spoke Portuguese without a foreign accent. But I was still unsure. I also considered studying medicine. My father was a doctor and taught psychiatry for a while.

In the end, I chose medicine for a practical reason. It was the course that would allow me to start working soonest, giving me some financial independence. I remember feeling like I really needed to make my own money, because my situation at home was turbulent. My parents separated shortly after I started college at Rio de Janeiro State University [UERJ] in 1976, when I was 17 years old. In my third year of college, I had to start working to support myself. I wrote a health column for a local newspaper and started translating scientific articles for medical treatises and other technical books — something I still occasionally do for scientific journals. I worked at night and I worked quickly, which always helped me a lot.

I even ventured into poetry once. A friend convinced me to enter a translation contest organized by the Pontifical Catholic University [PUC] in Rio de Janeiro and I came second. I translated a short poem by T. S. Eliot called “Rhapsody on a Windy Night.”

In my second year of college, I discovered neuroscience. There were a lot of young people getting into physiology at the time, some of whom are still my friends, and I started to study the physiology of the nervous system. It was an area that was rapidly evolving. I was fascinated by the dialogue between science and the more philosophical conceptions of the mind.

We were beginning to use quantitative methods from other branches of science to study the nervous system. Because of my interest in mathematics, this made me really happy. We studied the trajectory of brain waves and integrated the quantitative aspects with the more descriptive side of physiology. It was a very interesting relationship between mathematics and the natural sciences.

When I was in my third year, Professor Carlos Telles returned from a stay in Germany and created the UERJ Pain Clinic. It was the first in the country. The idea was to bring together professionals from various specialties to treat patients with chronic pain. These were difficult cases — many of the patients had advanced cancer and a history of failed treatment.

I was 20 years old at the time and I was really shocked. Firstly, because these patients were being passed from one place to another without ever finding relief from their suffering. And secondly, because morphine and the other substances we used to treat pain could be addictive. I thought medicine existed to alleviate suffering, but I was discovering the other side of it.

The experience influenced me profoundly and led me to later work with drug addiction.

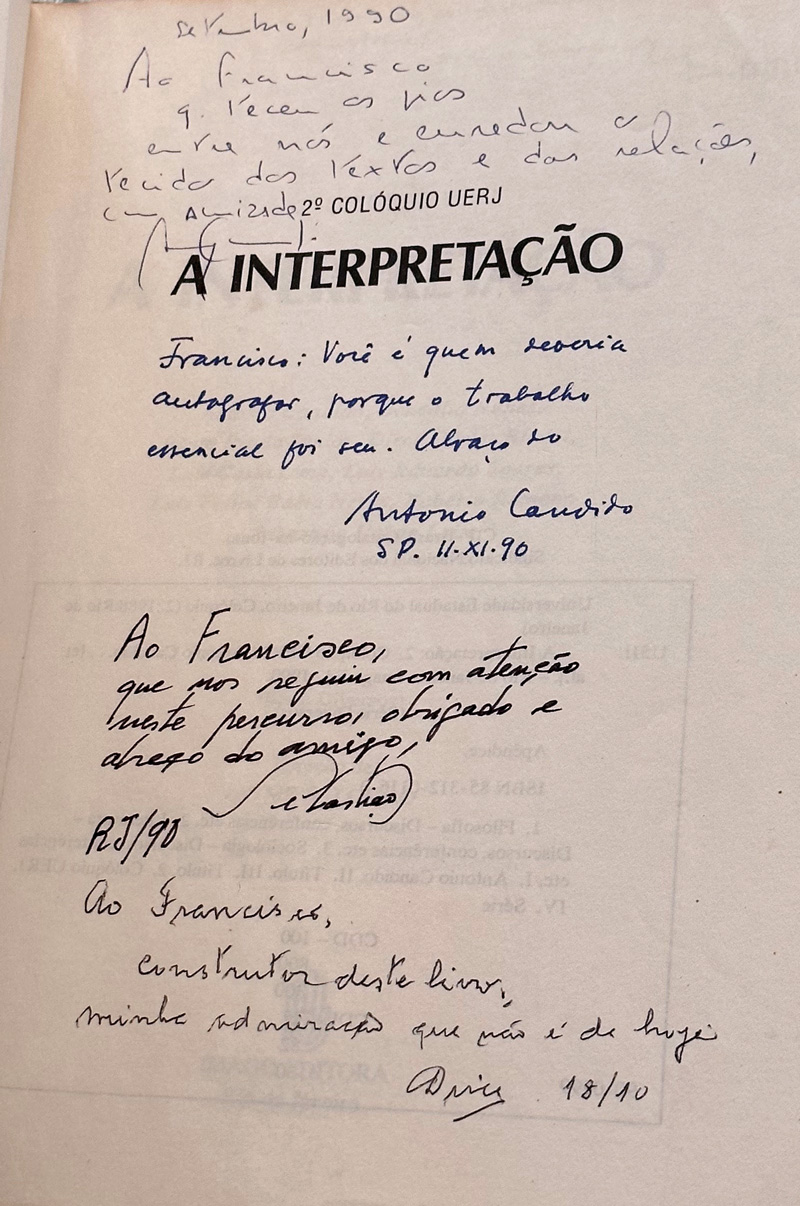

Ana Carolina Fernandes / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPOne of the titles in Bastos’s library. The book is about a colloquium held in 1988 by UERJ’s Institute of Languages and Literature, at which the doctor led discussions on translation and editingAna Carolina Fernandes / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

After college I did a residency in psychiatry and decided to pursue a master’s degree in the field, but then, by chance, I bumped into Professor Hesio Cordeiro on campus. He said that my ability with quantitative methods could be useful in social medicine and convinced me to do my master’s degree in the area. My dissertation was a more conceptual approach to the issue of drugs and addiction and how they have historically been addressed.

Around that time I was invited to work at a new UERJ clinic opened to treat drug addicts, so I left the pain clinic. Studies on the subject were very incipient in Brazil and there were few people with the experience needed to address the issue. There was a lot of talk about marijuana, but almost no one was talking about substance abuse and more serious issues.

After I completed my master’s degree in 1988, I took a three-year break. I continued working at the clinic, as well as translating and editing books and technical journals, but I was unsure whether I wanted to pursue a career as a researcher. In the end I chose research and studied my PhD at the National School of Public Health of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation [FIOCRUZ], the institution where I still work to this day.

Working with drug addicts at the UERJ clinic greatly influenced my doctoral research, “Ruína & reconstrução: Aids e drogas injetáveis na cena contemporânea” (Ruin & reconstruction: AIDS and injectable drugs in contemporary society). At the clinic, my focus was on the risks and harms associated with drugs. I began systematizing data on overdoses and accidents and I realized that many patients were infected with the AIDS virus. It was the mid-1980s, a time when it was still believed that only homosexual men could catch AIDS and many people thought that no one used injectable drugs in Brazil.

Intravenous drug addicts were highly stigmatized by other drug users and traffickers because discarded syringes would often lead to police involvement. In my PhD, which I did between 1992 and 1995, I used geoprocessing techniques to analyze the data collected in my research and showed a strong link between AIDS cases among drug users and cocaine distribution routes in Brazil.

I also spent a few months as a visiting researcher at the University of Hamburg in Germany, where I learned a lot about addiction prevention and treatment programs. There was nothing like it in Brazil. The first such programs only began to be implemented in the mid-1990s, and I was lucky enough to be involved in designing them.

I applied to work at FIOCRUZ after completing my PhD and started my career as a researcher there in 1997. I coordinated the national survey on crack consumption, published in 2014, and the national survey on drugs, the publication of which was vetoed by the Bolsonaro administration in 2019. We were able to publish a report and several articles, but we were not allowed to make the database with the full results available.

The debate on drug use is highly politicized worldwide, and I have no flair for politics. But I have had to learn to be diplomatic to carry out this type of research and deal with the immense pressure we face from the government and communities. The work of researchers needs to be seen as a public health action so that we can stand out from the prevailing confusion in this area.

Republish