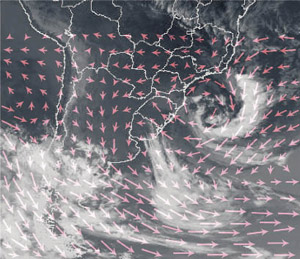

INPE / Journal of Geophysical ResearchArrows indicate the direction of the wind, and depending upon their size, the speed of the wind. The larger the arrow, the faster the wind speedINPE / Journal of Geophysical Research

The scientific community usually categorizes cyclones in the South Atlantic Ocean in the same way: as extratropical cyclones. However, upon studying three cyclones that formed close to the Brazilian coast, the researchers Rosmeri Porfírio da Rocha and João Rafael Dias Pinto, from the Atmospheric Sciences Department of the University of São Paulo’s Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics and Atmospheric Sciences (IAG/USP), concluded that the development of one of them was different from that expected for an extratropical cyclone in the region.

Published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in July of this year, the study seeks to explain the formation, evolution and dissipation of cyclones close to the Brazilian coast, so that in the future meteorologists will have more precise data available on the development of these systems. After all, ignoring this information could lead to incorrect meteorological forecasts or catch the specialists by surprise, as was the case with Hurricane Catarina.

Catarina struck in 2004, mainly affecting the States of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, and causing damage to roughly 60 thousand buildings. The damage in the State of Santa Catarina alone amounted to some R$ 200 million, according to the National Institute for Space Research (Inpe). While strong winds were blowing, the meteorologists were arguing as to whether Catarina was a hurricane or an extratropical cyclone – the lack of data and records on the passing of hurricanes over the South Atlantic Ocean made the analysis difficult. Confirmation came about mainly as a result of information gathered by international satellites, although measurements taken by Brazilian instruments played a part.

To offset the lack of information about cyclogenesis along the Brazilian coast, the researchers from IAG decided to study the behavior of three cyclones that developed in different regions where the phenomenon is more common. The first one chosen formed between the south of Brazil and Uruguay in August 2005; the second, in the River Plate region in June 2007; and the third was the cyclone from the south of Argentina in July 2008. All of them appeared as extratropical cyclones.

Any cyclone can start off as extratropical, subtropical or tropical and can change category, in other words, make a transition. “For example, Catarina started off as an extratropical cyclone that made the transition to a hurricane (also known as a tropical cyclone or typhoon). Their particularities are what differentiates one from the other,” explains Dias Pinto. Extratropical cyclones have cold and hot fronts associated with them and on average form in latitudes between 30° and 60º (in the Southern Hemisphere, from near Brazil’s southern region down to the south of Argentina) due to the difference in temperature between the equator and the cold coming from the poles.

Subtropical cyclones may or may not have fronts and, in general, form between the latitudes of 15° and 40° (which correspond to the area between Brazil’s Southeastern and Southern regions). Hurricanes have neither cold nor hot fronts and mainly develop due to the energy obtained from the evaporation of hotter ocean waters.

The tools chosen by the researchers to analyze the cyclones were a technique developed by Robert Hart, a professor at Florida State University, and the energy cycle theory developed by Edward Lorenz, the creator of chaos theory. Hart’s technique enables one to classify any cyclone regardless of its nature, whereas Lorenz’s model shows the origins of the energy used by the system to take shape and where this energy is dispersed to. “Both of these tools allow us to analyze cyclones in greater depth and to identify their different types, thus preventing another hurricane from catching us by surprise,” states Dias Pinto.

Applying these techniques, the researchers discovered that the first cyclone almost became subtropical. “The second one was an extratropical bomb, meaning that it developed rapidly and strongly in the space of 24 hours,” explains Dias Pinto. The average lifespan of a cyclone is three days. “The sea, under the effect of an extratropical cyclone of this intensity, creates huge waves in the ocean along with an undertow on account of the strong winds,” Rosmeri continues. In other words, it was an extratropical cyclone, but with characteristics that differed from the usual ones. Meanwhile, the third cyclone, which formed further to the south, turned out to be a typical extratropical cyclone, with all the characteristics that meteorologists expect.

Energy

Two main types of instability can contribute to the formation, evolution and dissipation of a cyclone. The most common source of energy in the Southern Atlantic is that of baroclinic instability, which is obtained when the cold air (more dense) and the hot air (less dense) meet, generating waves. Another source of energy is that of barotropic instability, generated by a change in the speed of the winds horizontally. “Using the combination of tools we managed to understand how these physical mechanisms act in regard to different developments and the strengthening of cyclones,” states Rosmeri.

If the meteorologists were to classify cyclones as extratropical during their entire development, they could get the forecast wrong: the rain could go on for days and the winds become stronger. “This is what happened in the case of Catarina. It started off as an extratropical cyclone and became a hurricane,” states Rosmeri. The meteorologists knew that it was a catastrophic event, but argued about its classification, in other words, whether it was a hurricane or an extratropical cyclone. “On the eve of its hitting the Brazilian coast, each warning system – Brazilian and American – pointed to a different answer,” declares Rosmeri.

The researcher emphasizes: “We don’t want to predict the weather, but rather to explain the formation of the cyclones that hit the Brazilian coast. Understanding the evolution of the cyclones in the Southern Atlantic regions provides input for a better understanding of their life cycle and for pinpointing possible hurricanes.” According to Rosmeri, for the time being, using just numerical models to predict the evolution of a cyclone could lead to mistakes. “Most of the existing studies concern cyclones in the North Atlantic,” says the meteorologist.

Scientific article

DA ROCHA, R. P. & DIAS PINTO, J. R. The energy cycle and structural evolution of cyclones over southeastern South America in three case studies. Journal of Geophysical Research. v. 116, p. D14112. 26 Jul. 2011.