A recent experiment has provided a strong indication that there may be a third way of generating superconductivity, the capacity of certain materials to conduct electricity with no energy loss. According to a November 2024 article published in the journal Nature Physics, the effect of this new mechanism—to date only theorized, and different from the two processes proven to be associated to superconductivity—was measured in a ferrous compound. When cooled to a temperature close to absolute zero, 4 Kelvin (K), equivalent to minus 269.15 degrees Celsius (ºC), the material allows electrical current to pass with zero resistance. The study is signed by four Brazilian physicists, and nine from outside the country.

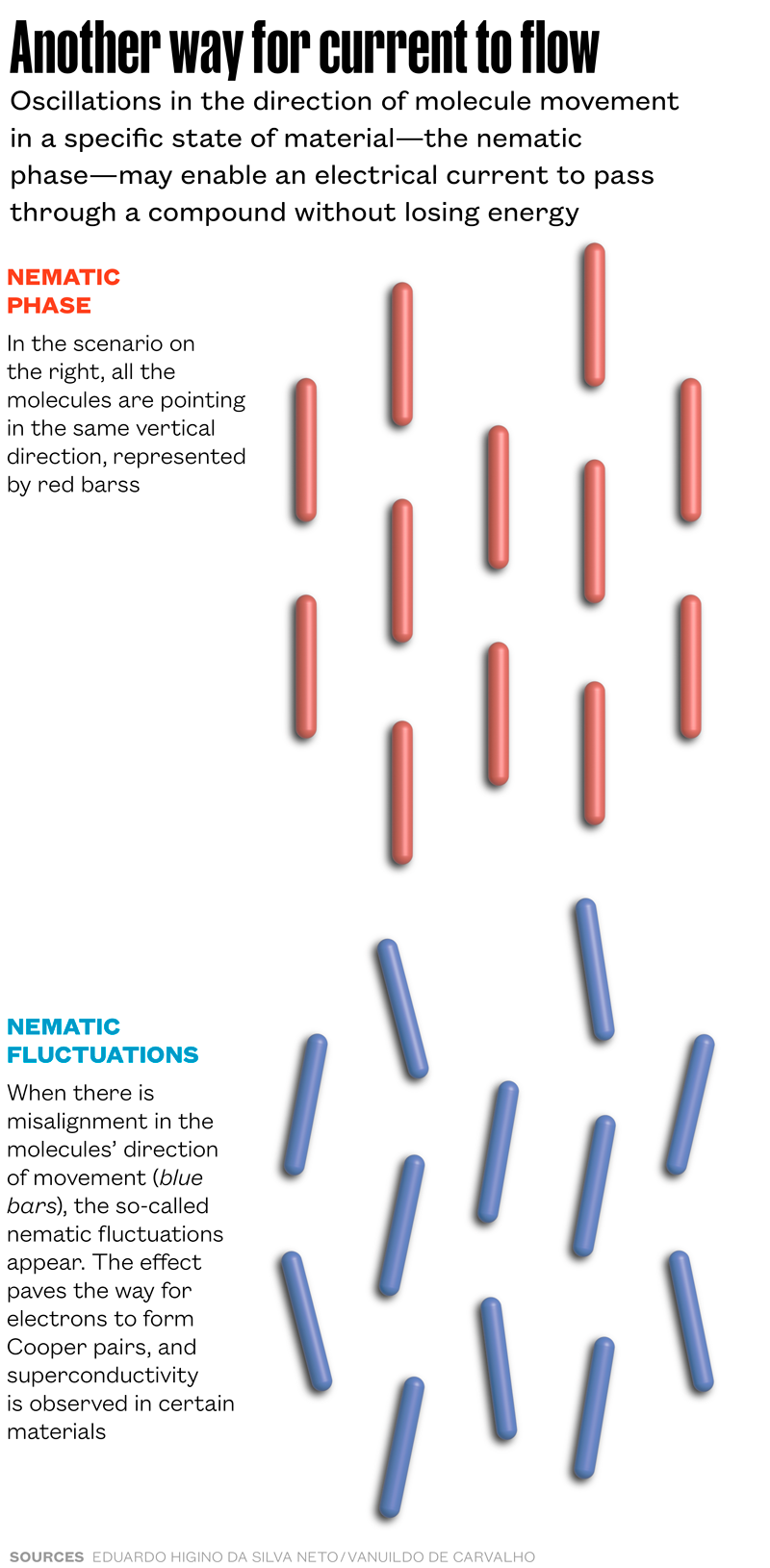

The research shows that superconductivity in iron selenate crystals doped (mixed) with sulfur atoms (FeSe1−xSx) may be brought about by a shift in a specific state of the material, known as the nematic phase. If the molecules of a material organize themselves in a certain direction (vertical or horizontal) and form a type of weave, similar to the lines of a fabric, the physicists say that it is in its nematic phase. In Greek, nema means thread. Manipulation of the nematic phase in liquid crystals, the material type in which this concept was originally formulated, is what enables the manufacture of today’s computer and LCD television screens.

In a configuration with its molecules fully ordered, and therefore in the nematic phase, the iron selenate preferentially conducts electrical current in the direction of their alignment. When sulfur atoms are added to this compound in the place of certain selenium atoms, their molecules no longer obey the original preferential alignment (vertical, for example) and start to move in a misaligned manner, with slight angulation. Oscillations in the preferential electrical current direction in the doped material generate these nematic fluctuations.

“Using a scanning tunnelling microscope, we found that the fluctuations are the probable cause of attraction between the Cooper pairs in this material,” explains Brazilian physicist Eduardo Higino da Silva Neto, of Yale University in the US, coordinator of the study. “The nematic fluctuations would be the third type of interaction causing the electrons to stick together and form pairs,” says theoretical physicist Vanuildo Silva de Carvalho, of the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), one of the study’s other authors.

When groups of two electrons—which having the same negative electrical charge should repel each other—approximate so closely inside the atomic structure of the material to the point of producing an uncommon type of bond between both, a Cooper pair is formed. This interaction needs to occur for an electrical current to flow in a zero-resistance compound without losing energy in the form of heat. The formation of Cooper pairs is the atomic signature that indicates superconductivity in a material.

To date, two mechanisms have been proven to lead to these electron pairs being formed when closer together. In most superconductor compounds, primarily those transmitting currents without energy loss only at temperatures a little above absolute zero, the Cooper pairs originate from a type of collective vibration or excitation of the atoms, known as a phonon. In superconductors known as unconventional, which function at higher, albeit still very low temperatures, superconductivity can occur due to the existence of a type of magnetic attraction: antiferromagnetism, in the electron spin, a quantum property intrinsic to electrons and other subatomic particles that influences their interaction with magnetic fields.

As the theory predicted

In unconventional superconductors it is very difficult to distinguish whether the capacity to transmit electrical currents without energy loss is due to antiferromagnetism, a more well-known and researched mechanism, or to nematic fluctuations, a less-studied effect in solid material physics. “In some superconductor materials, both phenomena act at the same time and can be confused. In others, antiferromagnetism is the cause of this property,” explains Silva Neto.

To measure the role of nematic fluctuations in inducing superconductivity experimentally, physicists had to create a material in which the two types of interaction in sample electrons could be separated. The objective was achieved through induction of sulfur atoms in place of certain selenium atoms in the original compound—the iron selenate. The more sulfur added to the material, the lesser the antiferromagnetic fluctuations, and the greater the nematics. “It was thus possible to rule out the possibility that antiferromagnetism was involved in superconductivity, with only the nematic fluctuations as the sole convincing explanation of our results,” concludes physicist Eduardo Miranda, of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), another of the article’s coauthors. The fourth Brazilian to sign the study was Rafael Fernandes, of the University of Illinois in the US.

“The article makes a very strong argument in favor of nematic fluctuations as one of the “glues” that generate the Cooper pairs,” says physicist Múcio Continentino, of the Brazilian Center for Physics Research (CBPF) in Rio de Janeiro, who did not participate in the study. Physicist Rodrigo Pereira, of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), also not involved in the work, goes along with this. “The study presents an impressive concordance between the theoretical argument of a superconductor induced by nematic fluctuations and the experimental results,” he comments.

The story above was published with the title “The third way for superconductivity” in issue in issue 348 of february/2025.

Project

Correlated quantum materials (nº 22/15453-0); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Eduardo Miranda (UNICAMP); Investment R$1,772,678.14.

Scientific article

NAG, P. K. et al. Highly anisotropic superconducting gap near the nematic quantum critical point of FeSe1−xSx. Nature Physics. Nov. 13, 2024.

Republish