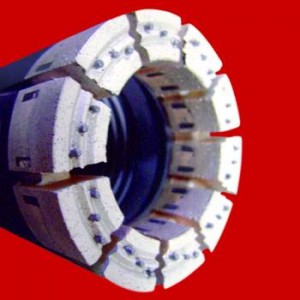

CLOROVALECrown with CVD diamond studs embedded at the tip of the drill for drilling bore holes and for minerals CLOROVALE

Although still lacking the transparency of natural stones, synthetic diamonds, which are dark and lackluster, are not made, evidently, for jewelry, but to aid several industrial sectors. Although they lack the beauty of genuine diamonds, the synthetic ones have equal physical and chemical properties, such as resistance to corrosion, hardness and heat conduction. These characteristics, adjusted to the technological development of production, led the company Clorovale Diamantes, from the city of São José dos Campos, in inner-state São Paulo, to devise to new projects with this material: a drill bit for oil prospecting and the protective coating of steel products or parts subject to chemical corrosion and wear through attrition.

“We are to deliver two drill bits to Petrobras this year. The company will test the parts on the seafloor, but not yet in the pre-salt layer, although the parts might be candidates for this,” says Vladimir Jesus Trava Airoldi, one of the firm’s partners and a researcher at Inpe, the National Space Research Institute, where the initial studies on this were conducted from 2002 to 2007, in the form of a thematic project financed by FAPESP. In the field of space, the importance of synthetic diamonds mainly concerns their fine film format, used to coat satellite parts, including solar panels, to dissipate sunray heat and protect the equipment from the bombarding of cosmic particles, while also functioning as a solid lubricant.

The technology transferred and subsequently developed by the company is financed by Pipe, FAPESP’s Innovative Research in Small Companies program. “These two projects were born out of the thematic project and then became two Pipe projects, after we had completed market studies on them,” says Airoldi. The coordinators of each Pipe project started in 2007 are Alessandra Venâncio Diniz and Leônidas Lopes de Melo, both of whom did their postdoctorates in the thematic project coordinated by Airoldi at Inpe. The company was also granted financing in 2006 from an Innovation Subvention project approved by Finep, the Studies and Project Finance Agency of the Ministry of Science and Technology.

The company was established in 1998 to absorb the synthetic diamond technology developed at Inpe, which found no interested parties in the market. Clorovale Diamantes was created from another Pipe project and in 2003 it launched its first project, a set of synthetic diamond tips for dental drill bits (see Pesquisa FAPESP nº 78), which was given the brand name CVDentus. The tips are attached to an ultrasound device and vibrate rather than rotate, which results in less aggressive and far less noisy treatment. Their other advantages are improved precision and greater durability. “Some four thousand dentists in Brazil already have these bits. We export to Latin American countries, such as Mexico and Costa Rica, besides Israel. We are now beginning to negotiate with Europe. Two companies seem to be interested in reselling the material to another 49 countries,” Airoldi tells us. However, the company is betting its chips on the domestic market, comprised of 140 thousand active dentists, which form a market that is yet to be won over. Estimates indicate that the foreign market for high-rotation dental tips amounts to US$ 500 million a year, whereas the Brazilian market stands at US$ 12 million a year.

CLOROVALEWithin the reactor, knife goes through the plasma process for depositing a fine diamond layer CLOROVALE

Partner and contacts

The company is preparing to receive by the end of this year an inflow of funds from Criatec, the Seed Capital Fund, through BNDES, Brazil’s National Economic and Social Development Bank, and BNB, the Bank of the Northeast of Brazil, in a venture capital operation whereby the institution becomes a partner in the firm. In this case, the ninth partner, which will join another eight, mostly Inpe researchers. Only two of the partners work directly on the company’s research and development efforts rather than at the Institute, while one works in the management area. “Criatec will help us to identify and better exploit the marketing and sales process in order to speed up production and develop the market, even abroad. It will bring new contacts for us to demonstrate our technology,” explains Airoldi. “It’s not enough to have an excellent product; one must know how to communicate the new product to customers.” The company has already professionalized its sales, administrative and financial areas and currently has 17 employees.

Clorovale Diamantes employs a chemical process, CVD (Chemical Vapor Deposition), to make synthetic diamonds (already used in some industrial sectors) and DLC (Diamond-Like Carbon) protective coatings. This technology is known in several countries, especially for new uses and concepts, such as the dental drill bits in Brazil. The production of these two new types of diamonds is based on gases such as hydrogen, methane and halogens, such as carbon tetrafluoride. Diamond production occurs within high-temperature reactors run at more than 2,400 °C and in the presence of plasma, a gas with electron loss and molecular modifications. Plasma is the source of the energy required to cause nucleation and the growth of the diamond coating. A number of other materials, such as silica, quartz and metals such as molybdenum and niobium are also among the ingredients of diamond production.

CVD technology is found not only on the tips of dental drills but also in drill bits used to bore into the seabed when prospecting for oil. “In the prototypes of the drill bits that are to be delivered to Petrobras, only those parts that grind stone have CVD diamond pins, attached by means of special soldering to the metal rod,” says Airoldi. The drill bit is some 50 cm long and the diamond-coated segment is almost 20 cm long. The diameter ranges from 10 cm to 40 cm. The complete part is being assembled by a firm that already provides services of this nature to Petrobras. Clorovale also developed a smaller version, which is currently undergoing trial; this too is designed for geology-related uses. “It has a ring-shaped crown that drills into soil and rock and collects samples for subsequent analysis.” The same CVD diamond is also appropriate for use in granite and ceramic cutters, replacing natural diamonds, as well as for use in industrial tool sharpeners.

The field of DLC applications is broad; it can be used in the automotive, textile, space, valve, pipe and tube industries, as well as in medicine. “DLC is regarded as a poor diamond because it isn’t as hard as the natural ones, but its features enable us to use it in coatings that stick to steel surfaces,” says Airoldi. This characteristic of DLC films makes it possible to protect steel from chemical corrosion and from material wear in parts that operate in constant contact with other surfaces. Several types of gears and industrial disks, besides tooth implants and knives, can be DLC-coated to stay efficient and wear out less over time. The material also functions like a solid lubricant. Studies in many countries have suggested using DLC films in automotive engine parts. Two components that deteriorate a lot are the piston pin and the exhaust valve plunger in the engine. “It is possible, in company’s reactors, to deposit DLC two to five micrometers thick on such parts,” says Airoldi. In Japan, more than two million automotive parts a year of just one of its automobile industries are already coated in this manner. “Here, we already have a project under way with one of the makers of automotive parts,” says the researcher, without revealing the company’s name.

CLOROVALESynthetic diamond point for sharpening tools CLOROVALE

Bactericidal steel

Another possible use for DLC is to coat the inside of pipelines carrying oil, gas, cellulose, ore, alcohol or other steel-attacking substance. “One can produce a uniform inside coating with DLC, which lends the pipes a longer life,” says Airoldi. One such innovation that the company is betting on is a bactericidal DLC film that enriches steel surfaces. This is useful to make medical and dental surgical instruments and to coat orthopedic parts. “This becomes possible if one adds silver or ceramic nanoparticles and increases the DLC bactericidal level, which is some 30% in any event, to about 70%.” The company has already applied for a patent for this process, has products that use the process in the prototype stage, and is looking for other firms to set up partnerships to market the innovation.

Even with many areas of operation and other areas to prospect, Clorovale Diamantes is not discarding the product most closely associated with diamonds, namely, jewelry. CVD diamonds are polycrystalline, meaning they comprise more than one type of crystal, which makes them black. The process to make this monocrystalline and transparent is difficult and expensive. “We are studying this possibility for the future,” says Airoldi. All these synthetic diamond solutions had some type of contribution from the thematic project that Airoldi conducted at Inpe. Overall, this project resulted in 13 PhDs, 7 master’s degrees and 11 scientific initiation projects and involved students from the University of São Paulo (USP), State University of Campinas (Unicamp), University of Vale do Paraíba (Univap), Federal University of Amazônia, Federal University of Pará, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Federal University of São Carlos, in São Paulo. It also involved researchers from the University of São Francisco (USF), University of Bragança Paulista, ITA (the Technological Institute of Aeronautics) and Paulista State University (Unesp), in Guaratinguetá.

The projects

1. New materials, studies and innovative applications in CVD-diamond and Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) (nº 01/11619-4); Type Thematic Project; Coordinator Vladimir Jesus Trava Airoldi – Inpe/Clorovale; Investment R$ 585,337.11 and US$ 24,638.00 (FAPESP)

2. Research, development and industrial production of nanostructured products (CVD-diamond and DLC); Type Financial Subvention Program for Innovation; Coordinator Vladimir Jesus Trava Airoldi – Inpe/Clorovale; Investment R$ 906,000.00 (Finep)

3. CVD-diamond for a new concept in high performance tools for drilling and cutting (nº 06/60821-4); Type Innovative Research in Small Companies (Pipe); Coordinator Leônidas Lopes de Melo – Clorovale; Investment R$ 415,876.72 and US$ 65,852.00 (FAPESP)

4. DLC films for applications on antibacterial, anti-attrition, spatial and industrial surfaces and for drilling oil wells (nº 06/60822-0); Type Innovative Research in Small Companies (Pipe); Coordinator Alessandra Venâncio Diniz – Clorovale; Investment R$ 415,876.72 and US$ 65,852.00 (FAPESP)