Personal archiveMy academic career was accidental and it did not evolve linearly. It did not start with me, but with the opportunities presented to my parents—after all, there is scientific evidence that socioeconomic status is intergenerational and can expand or limit a person’s possibilities. In this sense, my story begins before me. My father migrated from Northeast Brazil to the Southeast in search of work at the age of 14. He first settled in São Paulo, then in Minas Gerais. My mother is from Minas Gerais and for a long time she worked as a maid. Economically, my family was considered low-income. I went to a public school on the outskirts of Uberaba, a town in Minas. The students there, mostly from the poorest communities in the region, had no prospects for the future. Everyone—both the students and the teachers—felt completely hopeless.

Personal archiveMy academic career was accidental and it did not evolve linearly. It did not start with me, but with the opportunities presented to my parents—after all, there is scientific evidence that socioeconomic status is intergenerational and can expand or limit a person’s possibilities. In this sense, my story begins before me. My father migrated from Northeast Brazil to the Southeast in search of work at the age of 14. He first settled in São Paulo, then in Minas Gerais. My mother is from Minas Gerais and for a long time she worked as a maid. Economically, my family was considered low-income. I went to a public school on the outskirts of Uberaba, a town in Minas. The students there, mostly from the poorest communities in the region, had no prospects for the future. Everyone—both the students and the teachers—felt completely hopeless.

I did not understand the point of studying, I just wanted to finish high school and get a job. Until my older brother encouraged me to take the entrance exam at a public university, that is. I realized that social mobility was possible through education. I began studying for 15 hours a day. In 2007, at the age of 18, I enrolled on the economics course at UNESP [São Paulo State University], Araraquara campus. I was rewarded for all my effort when I graduated high school as the top student in my class.

My goal at university had been to earn a degree so that I could enter the job market. At first, I really wanted to do an internship—I did not see research as a professional occupation. But then I got involved in a research group that studied industrial economics, an area that really caught my interest. With a grant from FAPESP, I did an undergraduate research project in the field, under the supervision of Enéas Gonçalves de Carvalho. The grant not only legitimized the research, it also helped me to get out of a difficult financial situation.

When I finished my degree in 2010, I wanted new academic experiences. I decided to do a master’s degree at the University of São Paulo. I did really well on the ANPEC [National Association of Graduate Economics Programs] exam, which enabled me to study at the FEA [School of Economics, Administration, Accounting, and Actuarial Science] under the supervision of Joe Akira Yoshino, with a grant from the CNPq [Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development]. During my master’s and PhD, because of my financial situation, I had to live in the São Remo favela next to the university campus in the Butantã neighborhood.

Graduate school was a time of discovery for me. I experimented with different fields of economics—I was unsure what field I wanted to focus on. For my master’s degree, I studied financial economics. I immediately realized that it was a mistake. I struggled to identify with the subject and with certain aspects of the worldview of the research community in the area. I even received a few job offers during this period, including some with excellent salaries, but I turned them down due to my lack of enthusiasm for the field.

Although I achieved good grades and results, completing a master’s degree in which I estimated Brazil’s risk premium was exhausting. In 2015 I represented USP at a world econometrics competition in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Our team did not reach the final, but we were among the few that managed to resolve the case study.

Personal archive

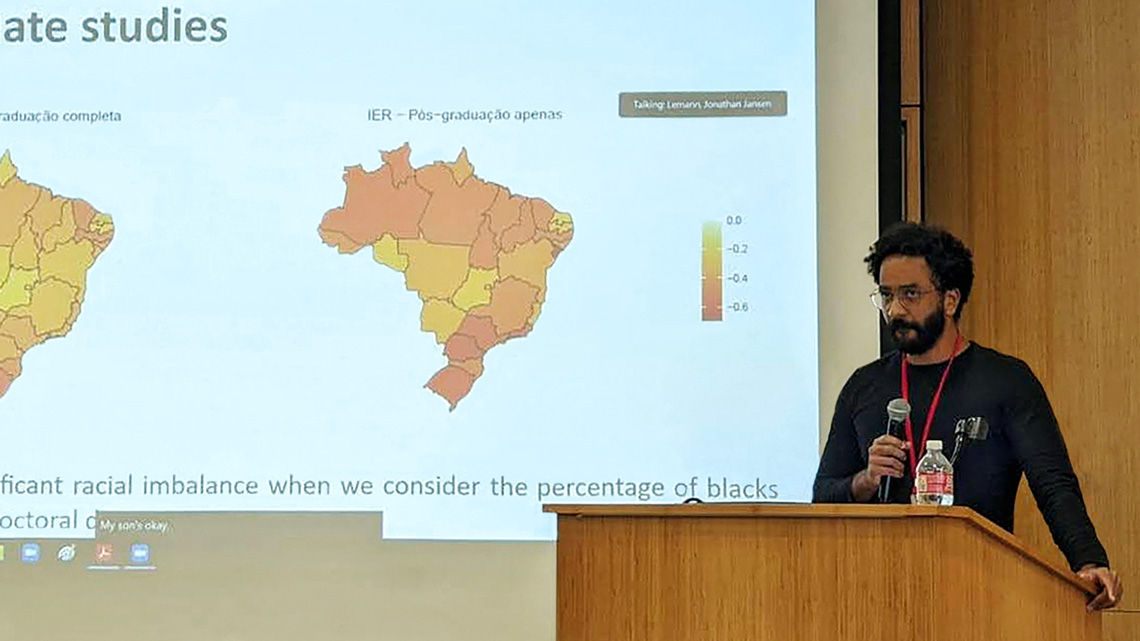

Michael França: in the classroom both in Brazil and abroadPersonal archiveI thought about giving up on my academic career. I was unmotivated by research in finance. I began to change my mind, however, after I found out that Professor Naércio Menezes Filho, from FEA-USP, was looking for a research assistant at Insper, another institution where he was also a professor. I successfully applied for the position, which gave me the opportunity to take part in a study testing the existence of an as yet unexplored effect of the federal government’s Bolsa Família welfare program. The objective was to verify whether the greater inclusion of poor students in public schools resulted in the best students migrating to private schools. For the first time in economics, I was dealing with social issues. The numbers on the computer were no longer just financial assets—they were people. It made a massive difference. I found the incentive I needed to continue in academia.

For my PhD, which I also studied at USP, I looked into social economy and I made an intellectual and personal discovery. I found my place as a researcher and gained a new understanding of my own path. My doctoral thesis represented a watershed moment in my career. I started my PhD in social economy in 2016, supervised by Eduardo Amaral Haddad. With funding from FAPESP, I was able to spend a research period abroad at Columbia University in New York, USA, under the supervision of Rodrigo Reis Soares. In my thesis, I explored the relationship between fertility rates and socioeconomic development in Brazil. In addition to making income distribution estimates, I examined various types of data, such as on the climate and media.

In 2020, I started a postdoctorate at Insper under the supervision of Sérgio Pinheiro Firpo, who became a friend of mine. I investigated whether racial discrimination occurred at hospitals. The study found that at the height of the COVID-19 crisis, patients who self-declared as Black had less access to ICUs. The work had significant repercussions. Later, I contributed to other projects on the topic, such as the creation of a racial equity investment algorithm and development of the Folha Racial Equilibrium Index at the request of the newspaper Folha de S.Paulo. The issue of racism is still rarely studied in economics, which is why we created the Racial Studies Center at Insper in 2020, of which I am currently the director. The center has 14 researchers.

While this academic route may not have immediately made me an expert, it did give me a broader perception of the economy. At the age of 34, I can see that I have acquired the ability to interact across a range of areas and speak to people from different social classes. I am aware of how the world is seen by those living on the margins of society, as well as by wealthy people. This is reflected not only in the research I carry out, but in my participation in public debate, which gives me even more confidence to continue. Much of this I owe to Insper’s short writing course, which showed me that I knew how to write and could do it.

Despite my continuous effort to write in accessible language as a columnist for a major newspaper, I am aware that as a Black man, the country’s racial and social biases stop me from reaching certain audiences. Despite the academic cost of spending my time on activities other than research, I insist. I understand that technical and scientific knowledge is a force for social transformation. It is therefore my duty to try to deliver it to Brazil’s various social strata and groups.

I have a highly varied routine. My activities are divided between research, running the Racial Studies Center, writing my column for Folha de S.Paulo, and working as a visiting researcher at Stanford University in the USA. As a result of my published work and involvement at events, I have been asked to participate in the public debate and offer contributions on issues related to social inequality and public policies. In the future, I would not rule out participating in institutional politics, as a technical expert or candidate for an elected position. Actually, I have already received some interesting invitations. But so far, I have turned them all down.

Republish