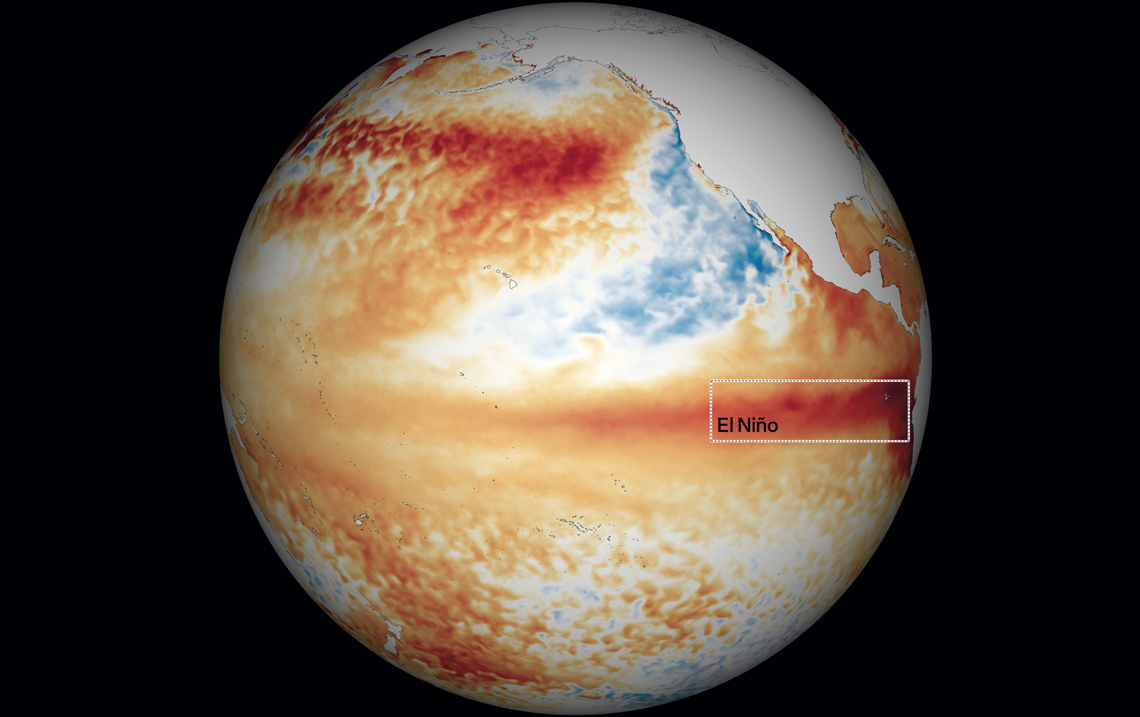

In the last weeks, news stories have proliferated about the probable arrival of El Niño, a climatic oscillation that alters the rainfall and temperature patterns in various parts of the world. In Brazil, the phenomenon usually causes droughts in parts of the North and Northeast and storms in the South. Since June, in accordance with reports from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), from the USA, the signs of El Niño, characterized by higher than historic average warming of the east and central waters of the Tropical Pacific, are clear. What is still unknown is the intensity of the phenomenon in the next months. The most recent predictions from NOAA estimate that there is around 80% chance of El Niño being between moderate and strong and only 20% chance of it being very strong between November this year and January 2024.

“Some models suggest that El Niño could be more intense, but others say that it will be moderate. Personally, I believe that we will have a moderate episode,” says meteorologist Tércio Ambrizzi, from the Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of São Paulo (IAG-USP). “This El Niño starts off moderate and has a chance of evolving to a strong intensity. But it is not possible to affirm that this will be the strongest of the last 30 years,” observes meteorologist Gilvan Sampaio, who is in charge of the Earth Sciences Department of the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE).

The concern is justifiable: in El Niño years, the scarcity of rain in the North and Northeast puts pressure on the water supply and leaves the Amazon more vulnerable to fires than normal. “The fires can spread more easily,” says Ambrizzi. In contrast, the South can suffer from excess humidity and rains, jeopardizing agricultural activity and causing floods. The scenario resulting from the climatic phenomenon in the Midwest and Southeast of the country, considered transition zones between these two great trends, are usually more uncertain: these regions can suffer from both excess and lack of rain.

What is El Niño

The Pacific, the largest of the oceans, covers around one-third of the earth’s surface. It is larger in size than all the continents put together. For around 90 years, scientists have been gathering evidence that natural fluctuations, of irregular frequency, in the winds and temperatures of the surface waters of the Tropical Pacific, especially close to the coast of Peru and Ecuador, are associated with changes in the patterns of rainfall and dry spells in different parts of the globe. These variations make up what meteorologists nowadays refer to as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

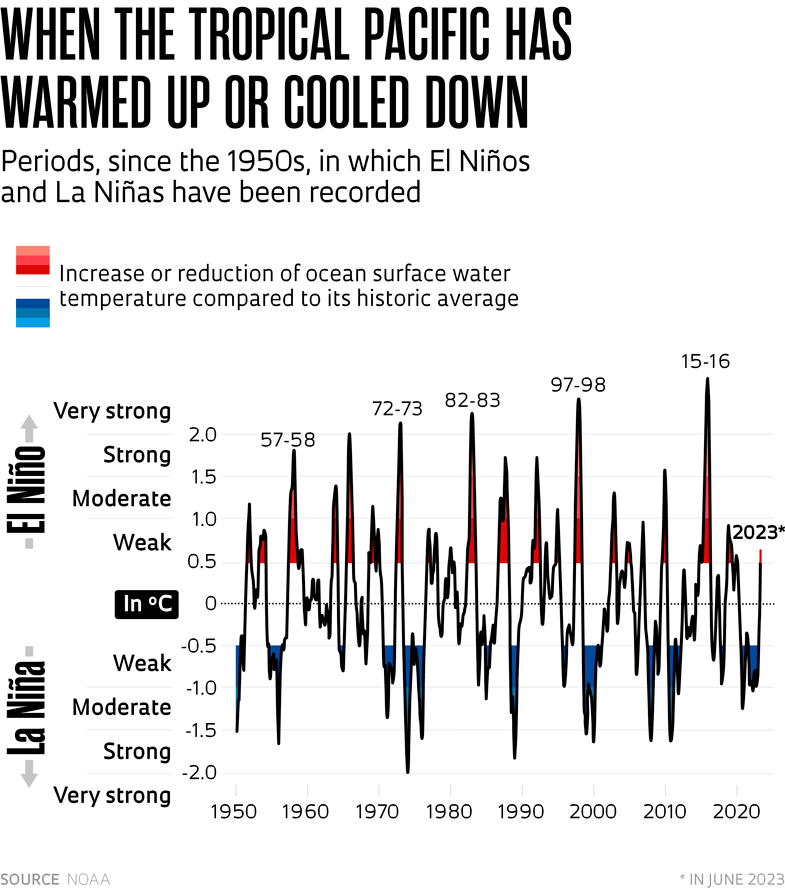

These fluctuations present three phases. When the waters from this region remain at least 0.5 degrees Celsius (°C) warmer than their historic average for over five months straight, the ENSO is in its phase known as El Niño, exactly what is probably starting now. If they are 0.5 ºC colder for the same period, the oscillation is in its La Niña stage. If the temperatures remain within the historic average, the ENSO is in its neutral phase. “It is important to remember that La Niña is the opposite phase of the same oscillation, the ENSO,” observes meteorologist Alice Grimm, of the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR). The effects on the climate of La Niña tend to be the inverse of those caused by El Niño. Whereas one makes it rain more, the other causes droughts, and vice versa. El Niños tend to occur at not very precise intervals, every two to seven years.

“In June, NOAA registered that the temperature of the Tropical Pacific was 0.5 ºC above the average from 30 or 40 years ago. But this isolated data does not necessarily mean that we are entering an El Niño,” explains meteorologist Michelle Reboita, of the Federal University of Itajubá (UNIFEI), in Minas Gerais. “NOAA only makes this warning because, besides verifying this warming, the climate modeling indicated that the surface temperature of this region of the ocean will not reduce in the coming months.”

In mid-July, the records from NOAA indicated that the warming of the Tropical Pacific waters was in the region of 1 ºC. An El Niño is considered weak if the temperature increase in the Tropical Pacific is between 0.5 and 0.9 ºC. When the warming is from 1 to 1.5 ºC, it is labeled as moderate. Above this, the oscillation is seen as strong. The classification is based on the temperature at the most critical time of the El Niño, at the end of the year, during summer in the Southern Hemisphere and winter in the Northern Hemisphere.

El Niño is linked to the pattern of atmospheric circulation. The rise in temperature of the Tropical Pacific occurs when the trade winds — which blow from east to west in the tropical region — become weaker and cannot push the warm water, which has been heated by the sun, to Asia and Oceania. “The warm water remains stationary in this stretch of the Pacific, evaporates more, and favors the appearance of rains in that region,” says Reboita.

Warm waters tend to stay in the more superficial areas of the ocean since they are lighter, or less dense, than cold waters, which accumulate in the deeper part. In normal situations, without El Niño, the trade winds take the warm and superficial waters from the Tropical Pacific of the Americas to Oceania and open space for the deeper cold waters to rise and take their place. This upwelling, called resurgence, usually occurs close to the South American equatorial coast. “These colder waters carry nutrients and stimulate the circulation of fish and other marine animals,” comments the researcher from UNIFEI, who coordinated a study about the impact of different climatological phenomena on South America in 2021. “That’s why, when there is no El Niño, fishing is benefited in locations such as Chile and Peru.”

“We don’t know what causes the weakening of the trade winds in El Niño periods,” says Ambrizzi. “It is not very clear whether it is the ocean that influences the atmosphere or the opposite,” he ponders. “It is difficult to know for sure what the variability of this phenomenon is, which in the last 30 or 40 years has appeared with greater frequency, every two or three years.”

It is a complex riddle, but there are clues to decipher it. Meteorologist Pedro Leite da Silva Dias, a colleague of Ambrizzi’s at IAG-USP, explains that the ENSO began around 2 million years ago, at the time of the closing of the Isthmus of Panama, which connected North America to South America. “Before that, the Pacific and Atlantic oceans communicated with each other. The closure was decisive for the occurrence of a significant change in the variability of the earth’s climate. El Niños and La Niñas started to be more efficient,” explains Dias. “The climate became more stable, with more intense glacial cycles, making space for the appearance of life as we know it. If the climate is bad due to the existence of ENSO, it would be even worse without this oscillation, which helps transport heat from the equatorial region to the poles.

Ambrizzi says that it is not possible to attribute with certainty the increase in the frequency of El Niños to global warming, which makes the atmosphere more unstable. “It is clear that the oceans are being heavily influenced by the warming of the atmosphere, absorbing part of the extra heat that reaches the surface. This relationship may exist, but we do not have scientific studies that show this conclusively,” says the researcher, who is the coauthor of a study about El Niño patterns in South America published last December in the journal Climate Dynamics.

Experts warn of the risk of making generalizations about the climatic impacts of an El Niño in each region of the globe and even in different parts of Brazil. “The effects of the phenomenon change throughout the seasons in the same way that the atmospheric circulation and solar radiation change during the year,” explains Grimm. El Niño normally begins in the winter (of the Southern Hemisphere) and ends in the fall of the following year. “In the South of Brazil, in El Niño years, it normally rains more than normal during the spring and fall. In the summer, this occurs more consistently only in the south of the region. In the North and in part of the Northeast, the impacts of the phenomenon are stronger in the fall and in the summer, the rainier period, and lead to a reduction of precipitation.”

In the Southeast and Midwest, the effects of El Niño — and La Niña — are not so consistent and typical. “The Southeast is a region greatly affected by the summer monsoon system [when humid masses of air coming from the Atlantic favor the formation of clouds that cause strong rains].” It is important to be aware of these variations, which may have repercussions on activities that are worth a lot of money, such as agriculture and the generation of electricity, and also on the lives of the people,” says the researcher from UFPR.

In June this year, Grimm was one of the coauthors of an international study published in the Journal of Climate about interactions of El Niño with another phenomenon, the Madden-Julian oscillation. This phenomenon, which lasts for one to two months, is a convective cell over the equatorial belt, which shifts from the west to the east. The merging of these two anomalies can change even further what is already out of the ordinary as a result of just the El Niño or the Madden-Julian oscillation alone. In the Southeast, the combination can produce more extreme episodes of rain in the summer. Its effects on the other regions, such as the South and Northeast, tend to be less severe.

Rising heat

Ian Willms / Getty ImagesToronto, Canada, covered by smoke from forest fires due to the high temperatures in JuneIan Willms / Getty Images

In the first week of July, the average global temperature record was broken three times consecutively. On Monday, July 4, the mark reached 17.01 ºC. The following day, it reached 17.18 ºC. On Thursday, July 7, it reached 17.23 ºC. The succession of records occurred after June 2023 had been considered the hottest June in history. The average temperature in June this year of the earth’s entire surface (continents and oceans) was 16.51 ºC, around 0.5 ºC above the historic average calculated for the period 1991–2020, according to data from the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

The expectation is that, during the peak of summer in the Northern Hemisphere, maximum temperature records will be broken in different parts of the planet. Forest fires in several countries, such as Canada and Greece, are already happening. In June 2023, the amount of ice in the Antarctic was also 17% less than its average since this parameter has been observed by satellite, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). “We are used to seeing large reductions of marine ice in the Arctic, but not in the Antarctic,” says Michael Sparrow, head of WMO’s climate research division, in a press briefing.

Some researchers suspect that the current heat wave is already a consequence of an El Niño enhanced by the climate crisis, which has global warming as its main mark. Scientists heard by the US newspaper The Washington Post argue that these temperature records are only paralleled by what occurred around 125,000 years ago, before the start of the last ice age. In more recent times, something of this magnitude would have only occurred around 6,000 years ago, when a fluctuation in the earth’s orbit heated the planet in an abnormal manner.

Meteorologist Gilvan Sampaio, of INPE, corroborates this theory. He says that the climate models show that the above reasoning makes sense. The sequence of temperature records registered in the last decades of this century is a sign that there is a problem in the functioning of the earth’s system. “The greenhouse effect has always existed, but its increase caused by the climate crisis leads to the occurrence of temperature peaks very close together. Global warming occurs very rapidly, and the natural systems do not have time to adapt,” warns Sampaio.

Republish