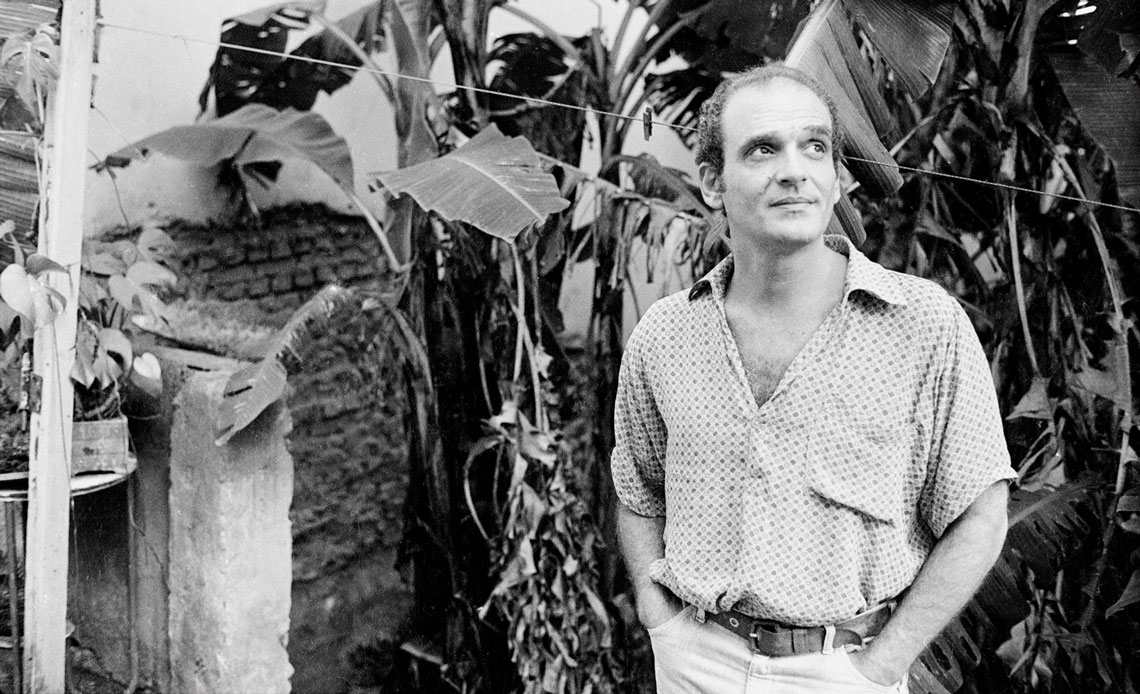

A graduate from the School of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (FAU-USP), where he was a professor between 1962 and 1977, Flávio Império (1935–1985) became one of the most important names in Brazilian scenography, producing paintings and working on performances with emblematic figures from the national scene, such as singer Maria Bethânia and theater director José Celso Martinez Corrêa (1937–2023). Planned for May, an exhibition in the Pinacoteca Estação building, in downtown São Paulo, aims to showcase the legacy of the multitalented Império, with 2025 marking the 40th anniversary of his death.

“He is one of the central characters for understanding Brazilian culture between the 1960s and 1980s,” states Yuri Quevedo, curator of the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo and responsible for the exhibition. The retrospective will include around 300 items, such as costume designs and three super-8 documentaries directed by Império. It is the case of Colhe, carda, fia, urde e tece (Harvesting, carding, spinning, twisting, weaving; 1976), which depicts the step-by-step process of manual weaving in the Triângulo Mineiro region. “Our idea is to show how Império repeatedly turned to popular culture throughout his career,” adds Quevedo, a professor of art history at the School of Architecture of the Escola da Cidade (São Paulo).

One example of the artist, architect, scenographer, and costume designer’s appreciation for the theme is his scenographic design for the 1984 São Paulo Carnival parade. The documentation with Império’s signature was found in 2023 by architect Angelina Guana, of SPTuris, the tourism company of the São Paulo municipal government. The discovery occurred during the transfer of the institution’s historical collection to the São Paulo Municipal Historical Archive (AHM-SP).

At the time when Império designed the project, the samba school parades took place in downtown São Paulo. “Every year, the Carnival structure was set up and dismantled shortly after on Avenida Tiradentes. The process would be repeated the following year,” explains archivist Sátiro Nunes, coordinator of the permanent collection team of AHM-SP. “For this reason, it was necessary to create projects that addressed elements such as architecture, scenography, and signage,” adds Gauna.

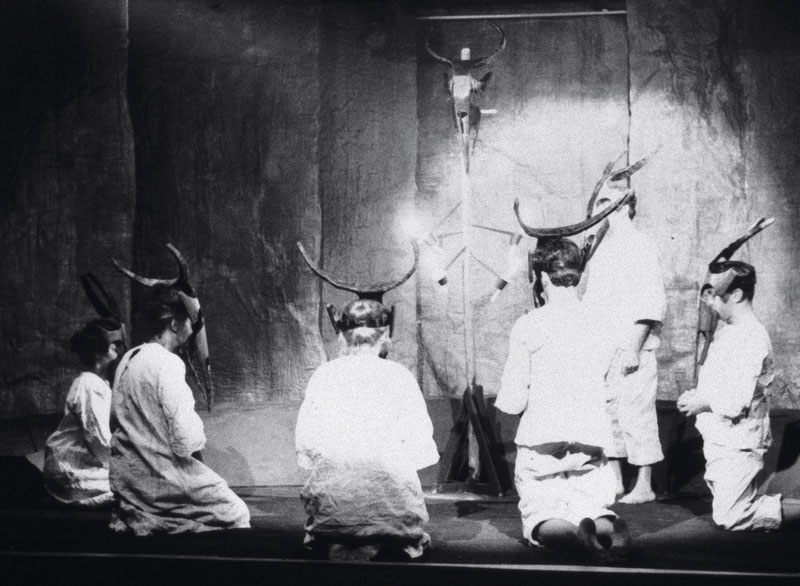

Fredi Kleeman / Flávio Império Collection / IEB-USPA scene from Morte e vida severina (1960) with set and costumes designed by ImpérioFredi Kleeman / Flávio Império Collection / IEB-USP

In order to adapt to the location and the available budget, Imperio’s project utilized the same metallic structure of the seating areas, with nine interconnected porticos across the 800-meter length. A series of flowers (red, orange, and yellow) and colorful lights (white, yellow, and red) were placed above the avenue, on the 17-meter-high porticos. During the day, the design was defined by the floral decorations, while at night, the shapes would be outlined by the lights. “The project paid homage to Brazilian popular festivals, but subtly, so as not to interfere with the performances of the samba schools,” says Nunes.

The sketch marks a new addition to his résumé. “He had never produced anything linked to Carnival and did the design at the invitation of visual artist Cláudio Tozzi [responsible for designing the winning logo of the 1984 event],” reports director of art Vera Hamburger, Império’s niece and one of the people responsible for the artist’s online collection, alongside curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti and architect Humberto Pio Guimarães.

The website, which has existed since 2015, is an initiative of the Flávio Império Cultural Society. It was created in 1987 by relatives, friends, partners, and former students, such as architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha (1928–2021), in the headquarters of the Brazilian Institute of Architects – São Paulo Department (IAB-SP). Initially coordinated by his sister, Amélia Império Hamburger (1932–2011), who was a professor at the Institute of Physics at USP, the entity seeks to make the extensive collection of documents gathered by the artist himself available. The physical catalog, composed of over 22,000 items, is currently under the guard of the Institute of Brazilian Studies (IEB) of USP.

One section of the digital collection is related to Império’s work in the performing arts. His professional debut in this field came in Morte e vida severina (The Death and Life of a Severino), an adaptation of the poem by João Cabral de Melo Neto (1920–1999) by the Cacilda Becker theater company, from São Paulo. For the production, which opened in 1960, he designed the set and costumes. “He projected photographs of migrants and tables with data on Brazilian social inequality. It was an innovation,” says architect Rogério Marcondes, author of the PhD thesis “Flávio Império, arquitetura e teatro 1960-1977: As relações interdisciplinares” (Flávio Império, architecture and theater 1960–1977: The interdisciplinary relationships), defended in 2017 at FAU-USP. “However, Império’s scenographic revolution took place through his partnerships with theater companies Teatro de Arena and Teatro Oficina.”

Flávio Império websiteCostumes from the Teatro Oficina production of the play Roda viva (1968)Flávio Império website

For the first, he worked on Arena conta Zumbi (Arena tells Zumbi; 1965), by playwrights Augusto Boal (1931–2009) and Gianfrancesco Guarnieri (1934–2006). The piece narrates the trajectory of Zumbi (?–1695), one of the leaders of the Quilombo dos Palmares, a refuge for enslaved people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. On stage, nine actors took turns to play the roles of nobles, slaves, and soldiers. “He dressed the actors in colorful shirts and white jeans, bought from a store on Rua Augusta, to bring Zumbi’s story closer to the present day,” continues Marcondes.

Império did the set and costume design for another milestone in Brazilian theater: the play Roda viva (Wheel of life), written by Chico Buarque. Directed by Martinez Corrêa, the production by Teatro Oficina was performed in 1968 in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Porto Alegre. “The costume was based on the traditional mesh fabric used by ballerinas to convey the idea of androgyny. He also created a catwalk extending from the stage into the audience, along which the actors walked and interacted with the spectators. “And, at the end of the performance, the cast took a real bull’s liver onto the stage, the blood of which spattered the audience.”

In his architectural work, Império was part of the Arquitetura Nova (new architecture), group, alongside architects Rodrigo Lefèvre (1938–1984) and Sérgio Ferro. Their partnership began at FAU in 1961, and the three colleagues soon shared an office in downtown São Paulo, which operated until 1968. About two years later, Lefèvre and Ferro were arrested by the military regime.

“The authorship of the projects was seen as a collective practice built over the course of intense interaction and the exchange of ideas, including with the engineers and workers on the building sites,” says architect Ana Paula Koury, from Mackenzie Presbyterian University, in São Paulo. “They used cheap materials, like concrete blocks, and dispensed with finishing in order to highlight the work process in the construction,” adds the researcher, author of a book about the group, launched in 2003, by EDUSP.

According to architect Felipe Contier, of UPM, Império’s only solo architectural work which was actually built is the Simão Fausto (1961) residence. “This project, built in Ubatuba [São Paulo], features innovations such as a garden on top of the vaulted brick roof. It was an experimental solution that, in addition to improving thermal insulation, celebrated craftsmanship and favored integration with the landscape,” explains Contier.

Flávio Império Collection / IEB-USPA drawing that is part of the project for the 1984 São Paulo CarnivalFlávio Império Collection / IEB-USP

The influence of architecture also marks Império’s work in the fine arts, such as in the series Construções (Constructions), from the 1980s. Besides paintings, he produced prints, collages, installations, and objects. “Império was an interpreter of everyday life. His work in the visual arts is an effort to understand how people lived and the solutions they found amidst the precariousness and underdevelopment of our country,” analyzes Quevedo, from the Escola da Cidade and author of the master’s dissertation “Entre marchadeiras, mãos e mangarás: Flávio Império e as artes plásticas,” (Among female marchers, hands, and banana hearts: Flávio Império and the fine arts) defended in 2019 at FAU-USP.

The title of the work makes reference to the work A marchadeira das famílias bem pensantes (The female marcher of the self-righteous families; 1965), one of the artist’s best-known paintings. In it, he criticizes the March of the Family with God for Liberty, which took place in 1964 to protest against the government of President João Goulart (1919–1976), which would be overthrown by the military coup. “In the 1970s, Império began dedicating more and more time to painting, an activity he practiced since childhood. Although he addressed clearly political topics in his drawings, it was in the visual arts that he created a more intimate space for reflection,” concluded Quevedo.

The story above was published with the title “A dive into the popular” in issue 347 of january/2025.

Scientific articles

KOURY, A. P. et al. Para ler Arquitetura Nova Brasileira: Arquitetos Flávio Império, Rodrigo Lefèvre e Sérgio Ferro. Arq.Urb. No. 29, pp. 01–03. 2020.

QUEVEDO, Y. F. A marchadeira das famílias bem pensantes: A pintura de Flávio Império entre o máximo e o neutro teatral. Arq.Urb. No. 29, pp. 78–86. 2020.

Book chapter

MARCONDES, R. Teatro, arquitetura e ditadura: Um recorte na carreira de Flávio Império. In: RIBAS, M., MENDES, R. (Ed.). Modernismos pra lá e pra cá. Campo Grande, MS: Editora dos Autores. 2022.