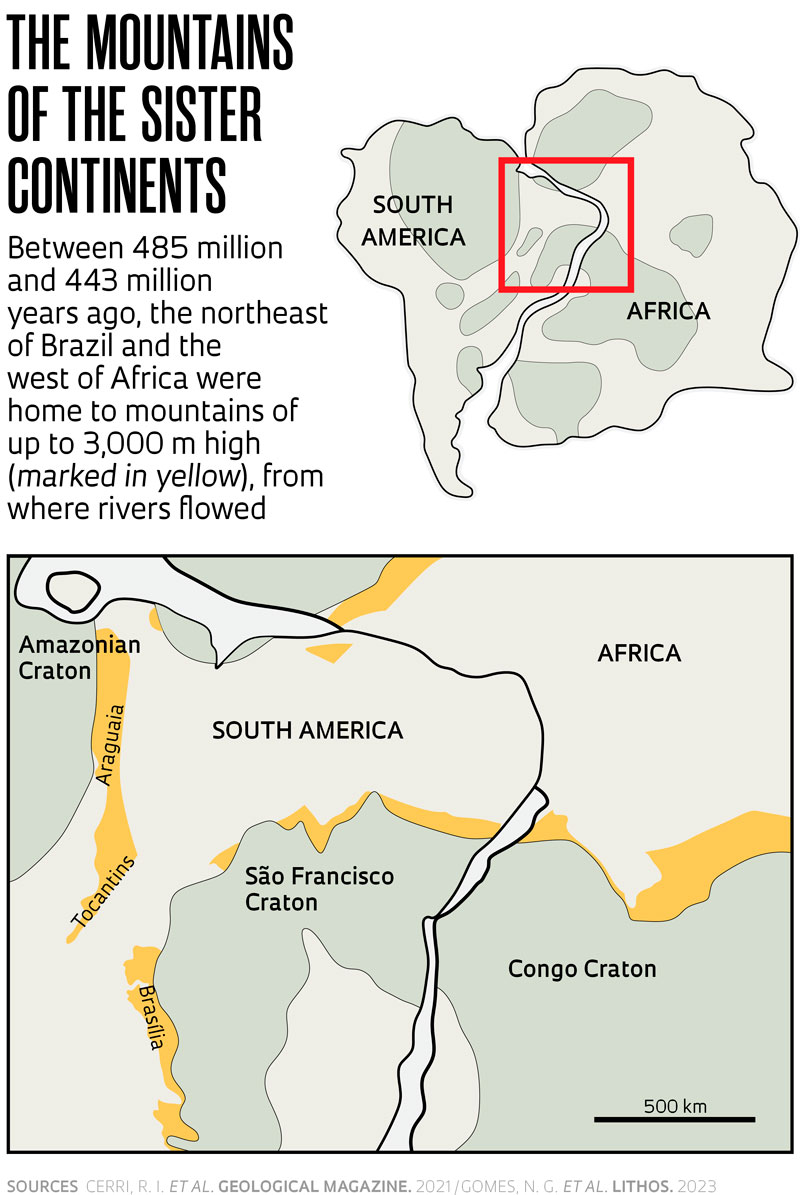

If you are in the region of Sobral and Juazeiro do Norte, in Ceará State; Catimbau, in Pernambuco; or Monsenhor Hipólito, in Piauí, you will probably find sandstones — yellowish rocks formed by sand compaction, whose layers indicate that millions of years ago, a river ran through these areas. Additionally, in the flat areas to the south, covering the states of Sergipe, Alagoas, Bahia, and Pernambuco, there were mountains between 3,000 and 4,000 meters (m) in altitude.

“The rivers that ran through the Brazilian Northeast between 480 million and 445 million years ago were different from those found there today,” comments geologist Rodrigo Cerri, of São Paulo State University (UNESP). “They were possibly intertwined, and transported sediment through vast, gently undulating areas, probably with no vegetation.”

Cerri says that there was a network or system of rivers, each 300 to 500 kilometers (km) long — more extensive, therefore, than the Capibaribe, at 240 km, whose source is in the sertão (badlands) of Pernambuco, passing through state capital Recife to the sea. Although different in origin, they would have been similar to the São Francisco or Amazonas rivers, with sources in the mountains of Minas Gerais and the Peruvian Andes respectively, making their way to the Atlantic Ocean.

Four hundred million years ago, the region that would become northeastern Brazil was still joined to what is currently North Africa, forming a continuous geological chain that extended to the Middle East, with rivers descending from the mountains, also now extinct. As the Atlantic had not yet been formed, the rivers discharged into the sea north of the current Brazilian northeastern region and the west of Africa, in sections where the two continents had moved apart.

Rodrigo Cerri / UnespSandstone layers indicating accumulation of sediments brought by waterwaysRodrigo Cerri / Unesp

This separation concluded around 100 million years ago, when the last rocky mass of 425 km, which connected what is today the state of Rio Grande do Norte and the south of Pernambuco to the coast of what are currently Nigeria, Cameroon, and Equatorial Guinea, is believed to have broken up; the Atlantic then had the space to form and widen.

Cerri drew these conclusions by examining sandstones collected in 2021 and 2022 from seven sedimentary basins (normally low-lying areas that accumulate silt) in the states of Ceará, Piauí, and Pernambuco. He says that the thick sandstone layers, built up over millions of years, present structures indicating the direction of the river after it was covered by other rocks and vegetation.

At the Rio Claro UNESP facility, Cerri ground the rocks and prepared seven samples, from which he extracted grains of the mineral zircon, with an average diameter of 300 micra (1 micrometer — plural micra — equals 1 thousandth of a millimeter). The zircon crystals incorporate chemical elements from the environment in which they are brought into being, based on magma, the viscous material forming the inside of Earth. The amount and type of each element indicate when and at what temperature and pressure the rocks containing zircon were formed.

One of zircon’s chemical elements is uranium, which, being radioactive, transforms — or decays — into a form of another element: lead. Older rocks contain less uranium (or more lead) and younger ones have more uranium (or less lead). A laser device zapped the mineral and transformed the uranium and lead into vapor. A mass spectrometer determined the proportion of the two components, and in turn the age of the rocks. The results indicate that the zircon probably came from older, and therefore higher lands than those on which they were found — geologically more recent and lower.

According to Cerri, the rivers disappeared and were covered in ice by intense glaciation at the end of the Ordovician geological period, between 445 million and 443 million years ago, as detailed in a June 2022 article published in Geological Magazine and another in the July issue of Gondwana Research.

“For some time, the discussion has been around whether river sediments in the Parnaíba basin across the states of Piauí, Maranhão, and Ceará, had the same origin as other basins in the Northeast,” says Cerri. “By studying zircon, we have demonstrated that all sedimentary units could indeed be of the same age, and have formed in the same manner.”

Geologist David Vasconcelos, of the Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), did not participate in the project, but studies sedimentary basins in Brazil’s Northeast region, and considers the hypothesis to be valid: “The older geological units of the northeastern sedimentary basins may really have had a common origin, despite the different regional names of the same type of sandstone.” Vasconcelos says that 480 million years ago, the rivers in these currently isolated basins may have been integrated in the so-called Afro-Brazilian Depression, formed by today’s Northeast Brazil and West Africa, vaster than the Amazon Basin.

“There is coherence in the information gathered, but you cannot a priori rule out that northeastern catchments had sources of sediments originating from several different sites, because rocks of the same age may occur in differing locations,” observes geologist Ticiano dos Santos, of the Institute of Geology at the University of Campinas (IG-UNICAMP), who did not participate in Cerri’s project, and studies the even more ancient geological history of the region, going back at least 550 million years, particularly in Ceará State. “At the mouth of the Amazon, for example, there are zircons of all ages from the Andes and older areas occurring along the Amazon River.”

Well known to geologists, the mountains of the current Brazilian Northeast formed in areas previously occupied by the sea as a result of the encounter between rocky blocks of the lithosphere (the surface layer of Earth) moving in the opposite direction. One of the high areas, the Sergipana Belt, currently covers the state of Sergipe and part of Bahia and Alagoas. Another, the Riacho do Pontal Belt, occupies the border region between the states of Bahia, Pernambuco, and Piauí, on the northern margin of the São Francisco craton (a craton is a block of ancient rocks extending for hundreds of kilometers).

Anyone moving around the interior of Brazil’s Northeast region who does not know much about geology should be careful not to draw hasty conclusions. Chapada do Araripe, for example, even at an altitude of 1,000 m and with 178 km of extension, is not a remnant of a mountain, but the result of compression of the denser rocky structures that surround it.

Projects

1. Geochronology and provenance of basal successions in the Parnaíba, Araripe, Jatobá, and Tucano Norte basins: Implications for the origin of the SW Gondwana intracontinental basins (nº 20/10739-7); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Lucas Verissimo Warren (UNESP); Beneficiary Rodrigo Irineu Cerri; Investment R$271,323.36.

2. U-Pb and sedimentary provenance analyzes of rutiles by LA-ICP-MS in the Paleozoic sequences of the Borborema province: Parnaíba, Araripe, and Tucano-Jatobá Basins (nº 21/12621-6); Modality Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Lucas Verissimo Warren (UNESP); Beneficiary Rodrigo Irineu Cerri; Investment R$156,768.04.

Scientific articles

CERRI, R. I. et al. The Early Paleozoic sedimentary record in northeastern Brazil: Unravelling the sedimentary provenance and evolution of fluvial systems after the western Gondwana assembly. Gondwana Research. vol. 131, pp. 237–55. july 2024.

CERRI, R. I. et al. So close and yet so far: U–Pb geochronological constraints of the Jaibaras rift basin and the intracratonic Parnaíba basin in SW Gondwana. Geological Magazine. vol. 159, no. 7. apr. 6, 2021.

GOMES, N. G. et al. P-T-t reconstruction of a coesite-bearing retroeclogite reveals a new UHP occurrence in the western Gondwana margin (NE-Brazil). Lithos. vol. 446–7, 107138. june 2023.