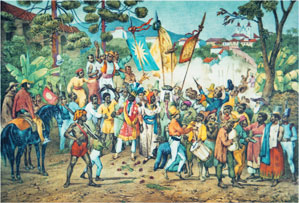

Jean-Baptiste Debret, Marimba – Sunday afternoon gathering. IEB/USP Above, groups of negroes, with typical African instrumentsJean-Baptiste Debret, Marimba – Sunday afternoon gathering. IEB/USP

The story resembles the script of the feature film Amadeus: a poor musical genius with natural-born talent, mulatto priest José Maurício Nunes Garcia (1767-1821), suffers horribly in the hands of his arrogant and jealous rival, Portuguese Marcos Portugal (1762-1830), the favorite composer of King Dom João VI. Marcos Portugal had come to Brazil in 1809 to be the monarch’s Kapellmeister and his reputation was that of a mediocre musician who was fond of palace intrigues. The third pillar of this “drama” is supposed to be Austrian composer, conductor and organ player Sigismund Neukomm (1778-1858), “Haydn’s most brilliant disciple,” a musician at the service of Charles Talleyrand (1754-1838), one of the organizers of the Congress of Vienna. Neukomm had been invited to compose a requiem for the Congress; the requiem was performed in great style in front of all the crowned heads of Europe. The Austrian, with a noteworthy professional curriculum, arrived in Brazil in 1816 and spent five years in Rio de Janeiro. During his stay, he was Dom Pedro and Dona Leopoldina’s piano teacher. In addition, he composed symphonies, music for mass, and transcribed popular songs for voice and piano. However, as an ardent admirer of the priest José Maurício, he was the butt of Marcos Portugal’s anger and finally, as a result, left Brazil in 1821. Mozart’s Requiem was part of the backdrop of this situation: in 1819, the priest and his European colleague got together for the opening performance of Mozart’s unfinished Requiem in Brazil, which was concluded by Neukomm.

“These opposites – the Portuguese villain, with close ties to the monarchy and Italianizing influences and the self-taught Brazilian musical genius – has resulted in a distortion of the true nature of the facts. This confusion worsened with the romantic view of Neukomm, Mozart’s contemporary maestro, who had allegedly come to publicize the ‘superior’ and ‘grandiose’ Germanic music in the tropics,” analyzes maestro and music specialist Ricardo Bernardes. “All of this was quite convenient in times of national self-assertion during the republican era (and sometimes still holds true nowadays), in an attempt to validate Jose Mauricio’s production and link him to Neukomm, as an anti-thesis to the ‘decadent’ Portuguese, personified in Marcos Portugal and later on, in Rossini.” Music as a state affair? “During the royal family’s time in Brazil, music was part of a much broader process; it was an additional element in colonial relationships. It is possible to reflect on the practice of music in the time of Dom João VI from the point of view of building up a ‘taste’ for music. The guidelines established by the king gave a new direction to the country’s cultural life by proposing changes and suggesting cross-links between the various modes of performing and listening to the sounds of the world as it was changing,” analyzes historian Maurício Monteiro, author of A construção do gosto: música e sociedade na corte do Rio de Janeiro 1808-1821, his doctorate thesis which has now been published as a book by Ateliê Editorial.

Comfort

“Even if the objective was to improve the physical conditions, thus allowing the royal family and the Portuguese nobility to enjoy some comfort during their stay in Brazil, the initiatives taken by dom João VI launched the basis of a civilization-building process that resulted in our political independence in 1822,” adds André Cardoso, the author of Musica na corte de dom João VI, published by Martins Editora. “The arrival of Neukomm and Marcos Portugal represented the stylistic continuity of a European style. José Maurício, the colonial representative, was the vortex to which the rehearsed styles of the two Europeans converged. Within this cultural melting pot, the musicians were able to contribute towards the construction of a taste that was being shaped, in and out of the royal court, as one of the premises for the process of implementing an awareness of civility and nation,” points out Monteiro. “This notion of nation does not reflect the awareness that moves the spirit of liberty, but rather an ideal notion of superiority in the form of this intended civilization.” This was a “war of sounds,” linked to a broader context which, catalyzed by the Napoleonic invasion, brought the Portuguese court to Brazil: the re-creation of “a flourishing empire” in the New World, as pointed out by historian Kirsten Schultz in her Versalhes tropical. “For the Portuguese, the transfer of the court was a chance to restore the moral and political integrity of the Portuguese nation, viewed at the time as being decadent and corrupt, thus rendering the Portuguese monarchy more formidable than ever.” This, adds the author, led to the creation of a Royal Chapel in 1808 – located next to the royal palace – by the regent prince, for the production and fostering of religious music. This was a way of “reinforcing the ancient tradition of the monarchy’s traditional fostering of religious music,” and providing the monarchy with a vision of progress, order and civilization, necessary to achieve the new Portuguese status.

Johann Moritz Rugendas, Feast of Our lady of the Rosary. IEB/USP. Feasts in the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries: religious celebrations lived alongside the miscegenation in the streetsJohann Moritz Rugendas, Feast of Our lady of the Rosary. IEB/USP.

Miracle

This is why Neukomm, who had come to Brazil as a member of the mission led by the Duke of Luxemburg – the objective of which was to re-establish diplomatic relations between France and Portugal – was hosted by the Count of Barca, the former Portuguese Ambassador to France; the count extended an invitation to Neukomm to spend some time in Brazil to witness the “miracle”: “We hope to establish a New Empire in this New World and it would be interesting for you to be a witness of this development period.” Although accustomed to the political environment in Europe, the Austrian had no idea that his music was aligned with Dom João’s ideology of being the sound track for his New Empire. “Neukomm was an isolated case of instrumental tradition in an environment which gave value, above all, to religious music and its relationship with opera. Before and after Neukomm, the scant examples of instrumental music comprised the opening arias of operas or openings of festive ceremonies, especially the religious ones. Music originally composed in Brazil was composed for the theater and the church,” Bernardes points out. Europe in the early 19th century was living in an era which witnessed the creation and proliferation of symphonies, of purely instrumental music. “At that period in European society, the symphony genre was more important than Mass; in the colonial and Catholic organization of Brazil, religious practices still predominated,” says Monteiro. Thus, an apparently harmless and aesthetic dispute between musicians could reveal political ideologies: the need to build a flourishing empire, without the flaws of the Portuguese nation of that time, required a return to the “good times.” More specifically, to the times of Queen Maria I. “Operas and the predominance of religious baroque manifestations had increased during her time. Opera performances were, above all, a demonstration of the pomp and circumstance that surrounded kings. Opera, with its heroes, was the personification of the king himself and simultaneously conferred upon him power and glory, benevolence and justice,” Monteiro points out. This helps us understand Dom João VI’s efforts to, among other things, bring castrati – worth their weight in gold – to Brazil at a time when they were already seen as decadent in contemporary Europe. To “recreate” the new it was necessary to restore the old in the same manner.

At this point, music was serious business to Dom João. “The king is so eager about the music sung at the Chapel, that he refuses to lend it to outside feasts, which he does not attend. When he was told that the Requiem composed by Marcos had been performed at the queen’s funeral rites, he exploded in anger and promised to ban anybody who repeated this to Angola,” wrote the musician of the Imperial Chapel in 1819. Dom João also attempted to “clean up” the music of the mixed races which, up to that time, had dominated the musical scenario. “At that time in Brazil there was no such thing as a patron of the arts, from the Church or from the nobility. The professional corporate spirit environment predominated – the brotherhoods, the laymen’s congregations, the professionals who congregated around a given devotion,” explains Cardoso. “The predominant view was that musical activity was ‘manual labor,’ a ‘mechanical’ activity and, as such, was not an activity worthy of being engaged in by white people. Until the arrival of Dom João VI, approximately 90% of the musicians were of mixed race and were connected to the brotherhoods under the protection of their patron saint, as in the case of the priest José Mauricio,” adds Monteiro. This situation changed radically in the times of Dom João VI: 72.6% of the musicians were of European origin and, on the social level, white musicians gradually began to predominate over the half-breed musicians. But the national reality was relentless with the ideal of a renewed empire in the tropics.

“I can imagine the castrati leaving after a beautiful rendition of an opera or a mass composed by Neukomm or by Marcos Portugal at the royal theater or chapel and going out on Rua Direita and becoming absorbed by the sounds of the lundus and the drumbeats, which comprised the world of José Maurício. On the street, Apollo had to surrender to Dionysius; Apollo reigned where European music was performed, while Dionysius dominated the environment in the street,” laughs Monteiro. The same happened when the two aesthetic forms clashed. Rio de Janeiro’s music community was demanding and depended greatly on the king’s personal taste in regard to the appropriate music for the New Empire, which, in his opinion, linked sacred music to theater music – just like in the times of Dona Maria I, far from the romantic paradigm of the superiority of the “pure” music of Haydn and Mozart. “There was a very fine line between the sacred and the profane, often not quite understood by contemporary audiences, who expected more ‘solemnity’ in religious works. They were very theatrical and full of profane elements. The opera-style music was brilliant, and this was demeaned by the romantic generation as a concession to fashion and as an example of the frivolous taste of an era that succumbed to Italian opera,” says Bernardes. “It must be understood that there was an adaptation of styles to a theatrical language when the royal family arrived in Brazil, in line with the monarch’s musical tastes, in a colonial Brazil where religious ceremonies were the major social event.”

JACOB HOEFNAGEL (1609)/CLAES JANSZ VISSCHER (1640)/WIKIMEDIA COMMONSTaste

JACOB HOEFNAGEL (1609)/CLAES JANSZ VISSCHER (1640)/WIKIMEDIA COMMONSTaste

Hence the reason for the change in style in the musical works of José Maurício when the court arrived. “The change may possibly have come from the musical tastes of Dom João VI, who, unhappy with the repertoire of the former Seat, orders musicians to come from Lisbon’s Royal Chapel and reorganizes the archives with original works. These works, which were supposed to be in the style of the works produced in Lisbon, had moved on to the opera language resorted to by Marcos Portugal. This was the musical standard for dom João VI and the Portuguese musicians, who revered him as a modern style composer,” says Bernardes. Far from being the mere “victim” of the “terrible” Marcos Portugal (a great composer who unfortunately is still relegated to limbo because of the dispute in which it was “non-patriotic to refrain from saying negative things about him”), José Maurício availed himself of the best of two worlds – the world of Portugal and the world of Neukomm, and continued being attached, the researcher points out, to the fundamentals of Italian opera and choir music: the beauty of the singing which should take the listener to ecstasy, without the fear of linking theater and church. That, after all, was a battle “of heavyweights.” “I send you a high Mass composed by Neukomm who, as an Austrian citizen and a disciple of Haydn, deserves your blessing. My husband is a composer as well and would like to present you with a Symphony and a Te Deum that he composed. In fact, the two works are somewhat theatrical, through the fault of his professor (Marcos Portugal), but he wrote them without anybody’s help” wrote Leopoldina, the wife of the future Emperor Dom Pedro I, in 1821. Leopoldina wrote this letter to her father, the Austrian Emperor Francis I. This was the Germanic tradition confronting Italian tradition. But the husband’s unhappiness was useless, because the necessary music was the music of Portugal’s golden age. “The time of the court’s migration to Brazil was also a time that transferred the behavior of the nobility, the functions and the languages. These practices were proportionally repeated in Brazil,” says Monteiro. And what about Neukomm? More than half of his symphonies and chamber music were composed in Brazil; indeed, he is credited as having brought this musical genre to Brazil, where he often performed chamber music at the home of Langsdorff, the Russian Ambassador to Brazil. Likewise, Bernardes points out, his noteworthy achievement is that he composed nearly all of the instrumental musical works produced in Brazil’s colonial times.

Jean-Baptiste Debret, Oricongo – African Orpheus. IEB/USPThe berimbau, a single-string percussion instrument was widely used in Rio de Janeiro at the time of Dom João VIJean-Baptiste Debret, Oricongo – African Orpheus. IEB/USP

Mozart

Nonetheless, there is no record of the performances of his symphonies and very few references to the performance of his masses, whose style differed greatly from the “sacred-operatic” style in vogue at the time. For the feast of the Brotherhood of Santa Cecilia, in 1819, he helped José Maurício perform Mozart’s Requiem, for which he composed a “Libera me domine,” which concluded the unfinished composition. In an article published in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, in 1820, Neukomm enthusiastically praised the priest’s talent: “The concert left nothing to be desired. All the talent got together to welcome, with dignity, the foreign Mozart to this New World.” He did not enjoy the same success. “Neukomm, Haydn’s favorite disciple, had been appointed as the director of the Capela do Paço chapel. However, the musical culture of the Brazilian people was still not mature enough to enjoy Neukomm’s Masses, entirely written in the style of the most renowned German maestros,” naturalists Spix and Martius pointed out in their book Viagem pelo Brasil. The Austrian composer decided to take on new challenges. “Neukomm was the first composer to write serious music and use, in Brazil (and perhaps in the world), themes based on the country’s popular music. This is how he composed a capriccio for piano, based on a Brazilian Lundu, a particularly sensuous African slave dance-song which had been banned by the authorities. He also transcribed and harmonized 20 folk songs composed by Joaquim Manoel da Câmara, a black poet-musician who had never had formal music lessons. Thanks to Neukomm, we have access to the music composed by Câmara,” says musicologist Luciane Beduschi, who has just presented her doctorate thesis – at the Sorbonne – on the composer. Brazilian researcher Helena Iank was on the examination board.

She is also responsible for the recovery of the Enigmatic Canon For Eight Voices composed by Neukomm shortly before he left Brazil. The work was dedicated to the city of Rio de Janeiro. “The Canon’s enigma illustrates a personal document in which the musician reveals the mood he was in when he left the country in 1821.” Neukomm returned to Europe a mere ten days after dom João VI had left the country, because, according to the researcher, he feared the tense environment that had enveloped the country. “The text of the Canon is a dialogue on religious music, between by two rivals, in which Neukomm is one of the characters and the others symbolize those who opposed his musical training. At the end, he states that, if to be acknowledged he had to adapt to a style that he abhorred, then he preferred to leave Brazil,” Luciane points out. In the Canon, Neukomm asks: “What sounds so joyful in the temple, as if today was a Bacchus feast? Listening to such enchanting music, we resist well for hours on end. If you sing about death in such a joyful manner, then what does your song of joy sound like?” The rivals reply: “What does this imbecile want? We, who sing so joyfully, this makes us revered by the nobles and by the poor. This brings us money and glory and all those who resist our ways get poor and rot here.” The Austrian replies: “So I will take my suitcase and leave.” The Canon is entirely based on the letter “C”: a.ca.p.r.i.pri capricornia, carioca, corcovado: vado, addio. “It would not be an exaggeration to imagine that the word ‘C.a.ca.’ with which he begins the Canon, were more than the simple repetition of the first syllable of the word ‘capricornia’,” points out the researcher.

His bad mood was justified, but his hurt feelings were unnecessary, because, although his “Germanic” project was unsuccessful, so was Dom João VI’s Dream to implement a tropical empire in the tropics, to the sounds of the good old “religious and profane operas” of the times of dom João V and Dona Maria I. “Our musical melting pot was also a demonstration of our cultural diversity, in which European violins played along with Afro-American drums and American Indian rattling gourds,” Monteiro points out. Amadeus blended with the drumbeats.

Republish