A significant cut in the budget of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications (MCTIC) had an intense repercussion on the scientific community during the first half of 2017. At the end of March, the MCTIC expense and investment budget, not including personnel expenses, was capped at R$3.2 billion in 2017, 44% less than had been established in the Budget Act, and less than half of the budget pledged for 2014, which was R$7.3 billion. What does this cut represent for the funding of science and technology in Brazil overall? It will almost certainly have an impact on national Research and Development (R&D), which is the set of activities conducted by companies, universities and scientific institutions, which includes the results of basic and applied research, release of new products and training of researchers.

A significant cut in the budget of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications (MCTIC) had an intense repercussion on the scientific community during the first half of 2017. At the end of March, the MCTIC expense and investment budget, not including personnel expenses, was capped at R$3.2 billion in 2017, 44% less than had been established in the Budget Act, and less than half of the budget pledged for 2014, which was R$7.3 billion. What does this cut represent for the funding of science and technology in Brazil overall? It will almost certainly have an impact on national Research and Development (R&D), which is the set of activities conducted by companies, universities and scientific institutions, which includes the results of basic and applied research, release of new products and training of researchers.

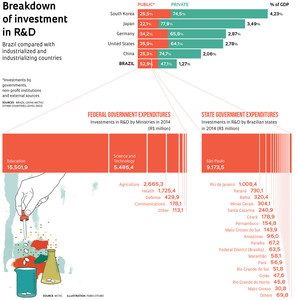

In 2014, the most recent year for which consolidated statistics are available, 1.27% of Brazil’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the equivalent of R$73.6 billion, was invested in R&D activities–and the share of the MCTIC (at that time, divided into two Ministries) was R$5.6 billion, representing just 7.6% of this investment. If these recent cuts are not reversed, the share of the MCTIC in domestic R&D expenditure is expected to fall from a level of 0.1% of GDP three years ago to a level close to 0.07% of this year’s GDP. It is still early to gauge whether the decline in the share of investment will be this large. “There is an expectation that the government will release funds in the second half. This type of replacement already occurred last December, when the MCTIC received R$1.5 billion from repatriated funds held by Brazilians in accounts overseas,” affirms Álvaro Prata, Secretary of Technology Development and Innovation of the MCTIC. “We are experiencing an unusual situation, but we hope the economy begins to grow again.”

It is also premature to predict the overall performance of R&D in Brazil for 2017. Other components of federal investments were also cut, but not as dramatically as in the MCTIC. The Ministry of Education (MEC), which accounted for some 21% of all the national R&D expenditures in 2014, saw a budget cut of 12% in March. Other MEC spending is concentrated in the federal universities and in payment of scholarships provided by the Brazilian Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (Capes). The budgetary allocation for the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), which is under the Ministry of Agriculture, has remained stable at around R$3 billion since 2015, even though this amount is insufficient, since it incurred a loss of R$490 million in 2016.

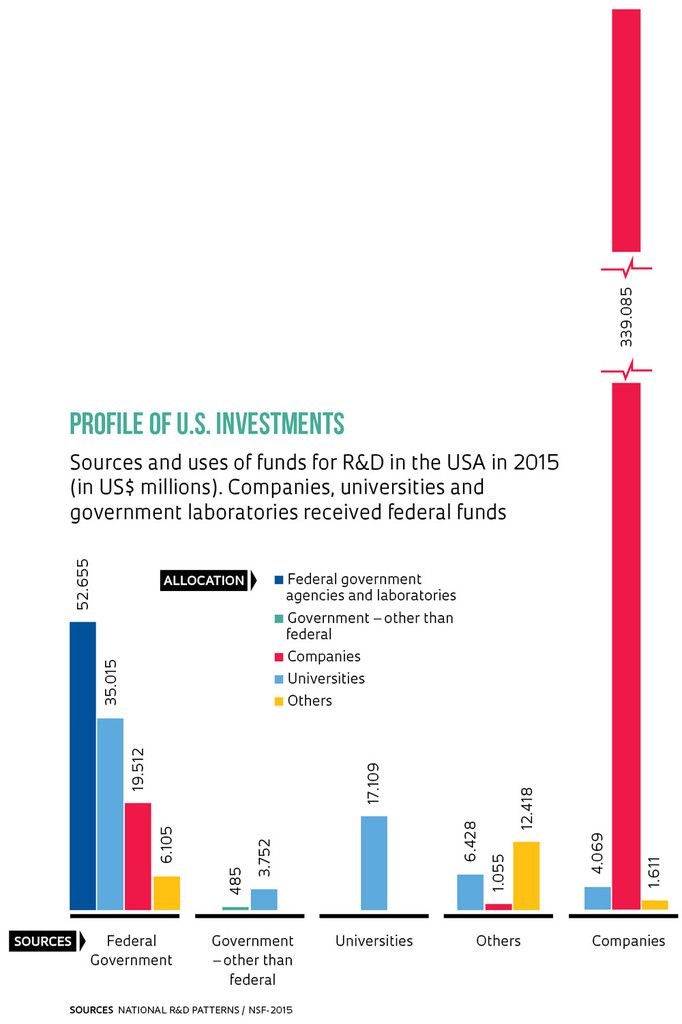

The R&D work done by the federal government is mainly focused on ministries such as the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health. “This profile is different from what we see in the United States, where the highest government expenditures occur in departments related to strong sectors of the economy, such as Defense and Energy,” notes Carlos Américo Pacheco, a professor at the Institute of Economics of the University of Campinas (Unicamp). “In Brazil, investments tend to be larger within the scope of the MEC and the MCTIC. Despite the greater attention paid by the private sector to innovation, matters related to science, technology and innovation in Brazil are still largely connected to universities and research institutes. As a result, it is hard to mobilize the economic area, such as the Ministry of Finance, and ministries in other areas to guarantee funding,” adds Pacheco, Chief Executive of the FAPESP Executive Board. Government expenditures on R&D include some funds spent by the states, which totaled R$12.8 billion in 2014, or 17% of the total–São Paulo State accounted for two-thirds of this, with expenditures by the three state universities, research institutions and investments made by FAPESP.

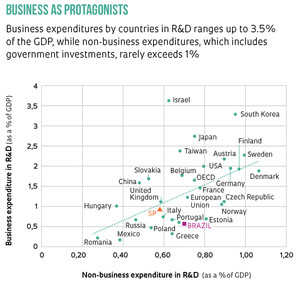

According to the document Estratégia nacional de ciência e tecnologia, (National Science and Technology Strategy), released by the federal government in 2016, Brazil proposed investing 2% of the GDP in R&D by 2019, a goal that is becoming increasingly harder to achieve. This is not an exorbitant level. The average investment by the 34 countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which includes some of the most highly industrialized countries, was 2.4% of the GDP in 2015. “Industrialized countries invest more than 2% of their GDP in science and technology. They are the ones we have to compete with,” affirms Helena Nader, president of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC).

In order to reach this level using the 2016 GDP of R$6.26 trillion, R&D investment in Brazil would have to be R$125 billion, which is 70% more than in 2014. “In those industrialized countries that invest more than 2% of the GDP in R&D, the share spent by companies always exceeds 1.3% of the GDP,” notes FAPESP Scientific Director Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz. “In OECD countries, where total R&D expenditures reached 2.4% of the GDP, 1.65% was spent by companies and the remaining 0.75% was spent by the government.”

In order to reach this level using the 2016 GDP of R$6.26 trillion, R&D investment in Brazil would have to be R$125 billion, which is 70% more than in 2014. “In those industrialized countries that invest more than 2% of the GDP in R&D, the share spent by companies always exceeds 1.3% of the GDP,” notes FAPESP Scientific Director Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz. “In OECD countries, where total R&D expenditures reached 2.4% of the GDP, 1.65% was spent by companies and the remaining 0.75% was spent by the government.”

The December 2016 promulgation of a constitutional amendment that imposed a ceiling on the increase in government expenditures makes it unlikely that there will be any growth in federal and state funding, unless some new financial engineering is able to identify other sources of funding, and has the political backing to be implemented. All eyes are on the private sector. In Brazil, the share of R&D investments by companies reached 47.1% in 2014, below that of the United States (64.1%), Germany (65.8%) and Japan (77.9%). São Paulo State is the exception within the Brazilian scenario, with 60% of the corporate investments in R&D. “Funding by companies is still quite meager in Brazil. In Korea, companies account for more than 70% of the total investments in ST&I,” notes Helena Nader.

In order for the Brazilian private sector to assume two-thirds of the national R&D investments, companies would need to invest around R$83.2 billion, 140% more than the R$34.6 billion spent in 2014. If this level of performance is achieved by business, to reach the goal of 2% of GDP, the government would have to invest around R$41.8 billion, a number that is close to the R$38.9 billion spent in 2014, albeit high for the current budgetary reality. “We need to remember that if the private sector does come to play this new role, the funds will be essentially allocated to research conducted at the companies themselves, as occurs everywhere in the world,” notes Carlos Américo Pacheco. “And since on average, governments subsidize around 15% of private R&D investments, this new level of expenditure will require more public funds to be allocated to companies.”

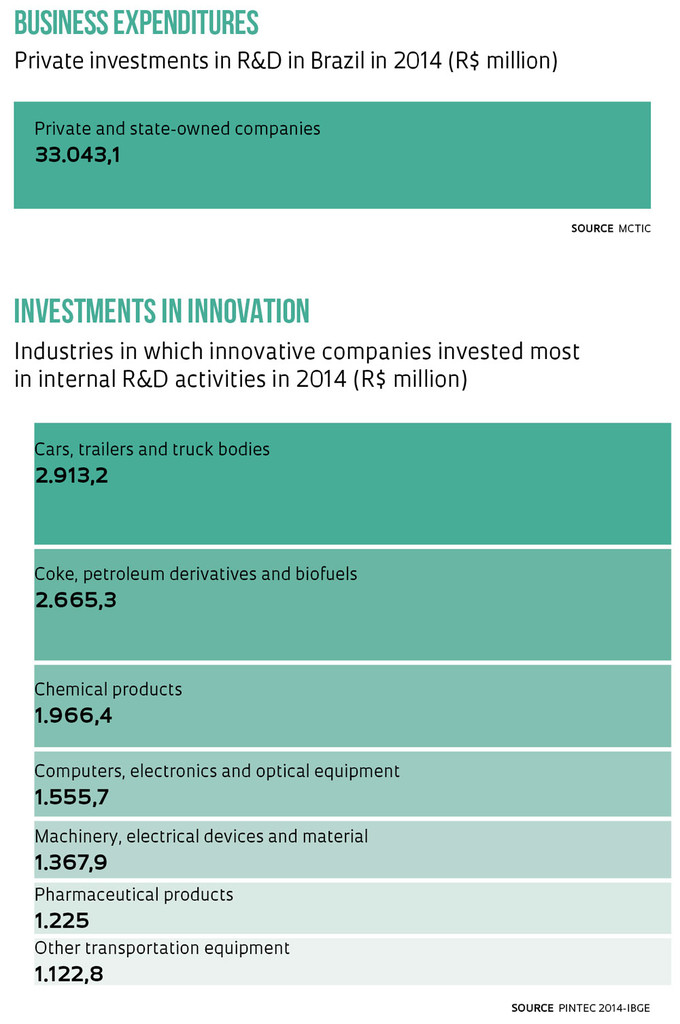

The capacity of the private sector to respond to this challenge is considered limited. Recent indicators suggest that private sector investments in innovation have lost steam. Corporate innovation in Brazil goes hand-in-hand with the acquisition of capital goods, which are those goods used to produce other goods, such as machinery and equipment. The performance of an indicator calculated by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) that measures increased spending on capital goods by companies, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), shows a decline. From February 2016 to February 2017, the accumulated decline of the GFCF was 7.9%.

There are structural problems that render it difficult to reach similar investment percentages as those of the OECD countries. Economist David Kupfer, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), sees problems on two fronts. One is related to the contribution to R&D efforts made by each sector of the Brazilian economy. Kupfer notes that important industries, such as natural resource extraction or food production require relatively modest levels of investment in R&D, while industries that rely heavily on innovation, such as the pharmaceutical and electro-electronics industry, are dominated by multinational companies with low rates of R&D investment in Brazil, since they tend to import it from their headquarters. “This model is not easy to change,” he affirms.

Another difficulty refers to the limited effectiveness of instruments designed to encourage innovation, such as incentive policies and laws. “These instruments were not successful at encouraging innovation in companies and industries that have traditionally been resistant to this type of effort. And they were also unable to leverage innovation at companies that were already innovative–to a large degree, the incentives given by the government just replaced investments that these companies might have made anyway, instead of multiplying them,” he affirms. For Luiz Eugênio Mello, vice-president of the Brazilian Association for Research and Development of Innovative Companies (ANPEI), the challenge does not exactly lie in increasing R&D outlays by companies, but instead, in mobilizing segments that invest little. “Petrobras is one of the companies that most invests in science in the world. However, in Brazil, industries like the pharmaceutical industry invest little, compared to what they invest in, in the United States and Europe. Investment in R&D by business will not change unless these industries mature,” says Mello, who is an executive manager of Innovation and Technology at Vale.

Another difficulty refers to the limited effectiveness of instruments designed to encourage innovation, such as incentive policies and laws. “These instruments were not successful at encouraging innovation in companies and industries that have traditionally been resistant to this type of effort. And they were also unable to leverage innovation at companies that were already innovative–to a large degree, the incentives given by the government just replaced investments that these companies might have made anyway, instead of multiplying them,” he affirms. For Luiz Eugênio Mello, vice-president of the Brazilian Association for Research and Development of Innovative Companies (ANPEI), the challenge does not exactly lie in increasing R&D outlays by companies, but instead, in mobilizing segments that invest little. “Petrobras is one of the companies that most invests in science in the world. However, in Brazil, industries like the pharmaceutical industry invest little, compared to what they invest in, in the United States and Europe. Investment in R&D by business will not change unless these industries mature,” says Mello, who is an executive manager of Innovation and Technology at Vale.

The quality of R&D expenditures by Brazilian companies is lower than that seen in other companies. The private sector in Brazil makes similar total R&D investments as those made by companies in Spain, but obtains a much lower number of patents. A study that compared patents granted in the United States shows that Brazilian companies obtained 197 registered patents a year from 2011 to 2015, while Spanish companies attained an average of 524 per year during the same period. For Luiz Mello, there is a low level of R&D in Brazil, even among leading companies. According to data compiled by ANPEI, from 2011 to 2015, the 10 companies headquartered in Brazil that filed the most patent applications in the U.S. were Petrobras, Whirlpool, IBM, Embraer, Freescale, Voith, Vale, Natura, Pioneer and Tyco. “Together, they filed 392 patent applications. In turn, the 10 companies that filed the most patent applications in Spain, which were HP, Airbus, Ericsson, CSIC, Fractus, Gamesa, Vodafone, Laboratórios Dr. Esteve, Intel and Telefonica, filed 739 patent applications in the United States, 88% more,” says Mello. According to him, the low degree of R&D investment is a more serious problem than the often-criticized tendency for Brazilian companies to only produce incremental innovations. “Incremental innovations serve to strengthen the market positions of companies and increase their profitability. If we achieve a higher volume of patents, there will also be disruptive innovations among this critical mass.”

Álvaro Prata affirms that the MCTIC is seeking to leverage corporate investments in R&D, and he sees reasons to be optimistic. “We have a well-developed industrial base, with strong potential for growth,” he notes. In the next few weeks he expects a decree containing 83 articles to be signed that will regulate Law number 13,243, of 2016; this law updated and improved the legal framework to encourage innovation and interaction among private and public research centers. “This decree will provide security for industry to interact with the scientific world,” he affirms.

There is agreement between the government and the scientific community that new sources of funding must be found, and that existing resources must be used more productively. The SBPC is moving to strengthen private investments in public universities. Another front involves defining the regulatory framework for endowment funds, focused on obtaining donations from alumni and sponsors. There are bills currently before Congress that would make it possible for public institutions to have endowments with tax incentives for donations.

Institutional diversity

Institutional diversity

It is no small matter to guarantee the vitality of a science, technology and innovation system like the one in Brazil, which has become increasingly more complex in recent decades. It went from a model that supported individual research projects until the 1960s towards a system that supports graduate studies, turning out 18,000 PhD recipients a year and establishing a network of research groups that has tripled in size since 2000.

“The system for funding science in Brazil presents a degree of institutional diversity that is only found in developed countries,” notes economist and former Federal Representative Marcos Cintra, president of the Brazilian Innovation Agency (FINEP), an agency linked to the MCTIC. “With the budget cuts, we are at risk of losing all the work we have put into this. Any country that stops investing in science, technology and innovation distances itself from the cutting-edge of knowledge and gets left behind.”

This multi-faceted institutional universe has been shaped by tools and laws that established new business models, incorporated innovation into the S&T system and sought to encourage interaction between universities and business. One of the highlights was the creation of the Science and Technology Sectoral Funds in the late 1990s, designed to overcome the problem of instability in funding and to supercharge research in areas of interest to certain sectors of the economy. Other hallmarks were the Innovation Act (Lei de Inovação) of 2004, which authorized the investment of public funds in companies and allowed researchers from public institutions to perform activities in the private sector; and the “Lei do Bem”, a set of tax incentives for R&D to boost innovation, of 2005, which created tax incentives for R&D and technological innovation.

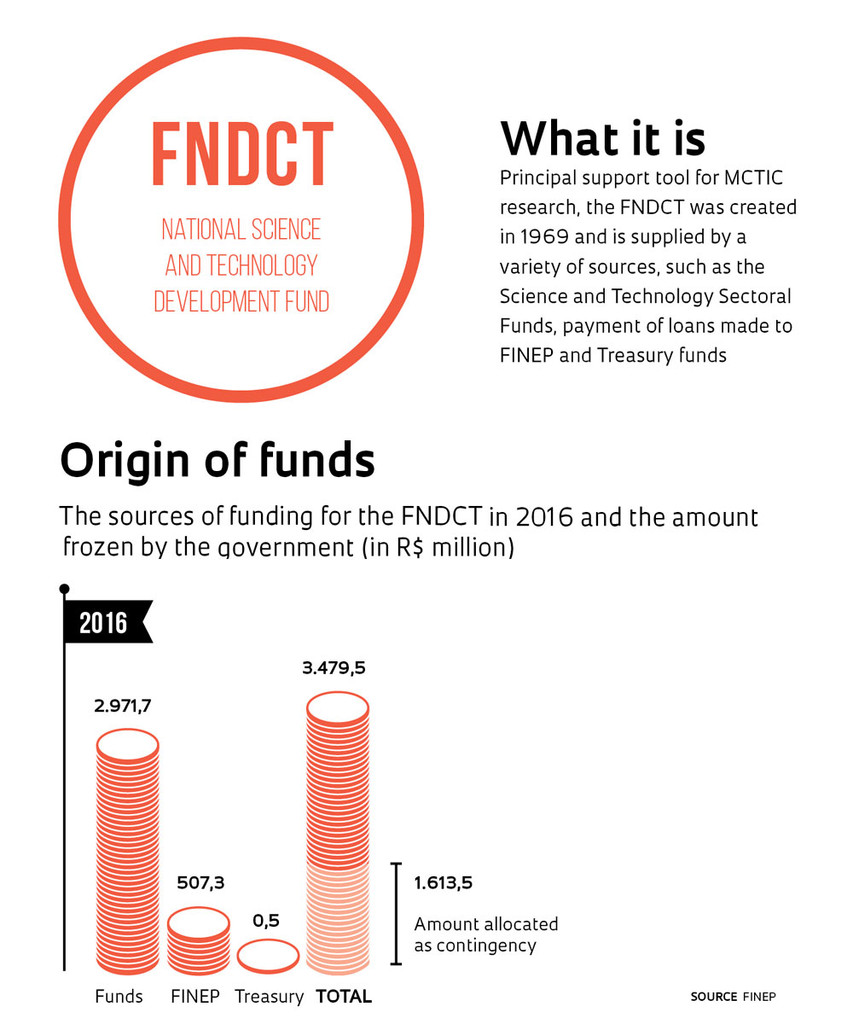

The current scenario suggests that some of these instruments are no longer effective. One example is the situation of the National Science and Technology Development Fund (FNDCT), the principal tool for providing support to MCTIC research projects. In recent years, this fund accounted for 30% to 40% of the Ministry’s budget – the rest was allocated for personnel and support for the Ministry’s departments. However, the FNDCT has been dealing with several setbacks. The most recent blow came from a decline in tax revenue. The Science and Technology Sectoral Funds, principal source of FNDCT funding, raised R$2.9 billion in 2016, 11.6% less than in 2015. Transfers from the Treasury to the FNDCT practically ceased–they fell from R$500 million two years ago to just R$500 thousand last year. The Fund is also supplied by a third source, which comes from FINEP. This agency borrows 25% of the funds allocated to FNDCT for reimbursable credit operations and returns the funds when it receives payment from the debtors. In 2016, FINEP deposited R$507 million into the FNDCT, compared to R$440 million the previous year.

From 2013 to 2015, more than R$2 billion from the FNDCT financed the Science without Borders program (CsF), even though training of human resources is not among the fund’s stated purposes (see report). Another obstacle involved the change in the rules governing the distribution of petroleum royalties, which caused a drastic drop in one of the most important sector funds, the CT-Petro, in the oil and gas area. Until 2012, the fund accounted for almost half of the sectoral funds contributed to the FNDCT and it lost most of this support when Congress regulated the development of the pre-salt layer. This reduced the total spent on CT-Petro projects from R$139 million in 2007 to R$4.5 million in 2016.

But the greatest damage to the FNDCT is caused by the freezing of funds. In 2016, the fund’s budget was set at R$2.6 billion, net of R$900 million loaned to FINEP. Of this total amount, 61%, or around R$1.6 billion, was transferred to a reserve fund, a euphemism for the expression “contingency allocation.” From 1999 to 2011, 48% of the total collected was allocated as a contingency, according to FINEP, which manages the FNDCT. “This is very serious. A significant share of the funds allocated for science is being used by the government to create a fiscal surplus,” says Helena Nader.

Of the 16 sector funds, 14 are linked to areas of the economy, such as petroleum, energy, health and biotechnology. Each of them are funded by specific revenue sources. For example, the energy area receives between 0.3% and 0.4% of the sales of utilities in the electricity industry. There are also two funds with a cross-sectional nature: the Verde-Amarelo (Green-Yellow) Fund, which focuses on projects that promote interaction between universities and companies, and the Infrastructure Fund, intended to promote improvements in the infrastructure of scientific institutions. The monies for these two funds come from 20% of the other funds. The original purpose of the funds was to guarantee the stability of the investments, principally by promoting research projects in those industries in which the funds were raised. The guidelines and investment plans for each fund are defined by management committees, composed of representatives of the government, the industry in question, and society. “The funds were designed to promote innovation in management and connect the different actors involved in the implementation of sector policies,” explains Carlos Américo Pacheco, one of the creators of the funds when he was executive secretary of the former Ministry of Science and Technology, between 1999 and 2002. “Over time, the sectorial dimension became less important, with cross-sectional actions taking on greater importance, along with the reallocation of funds to other challenges faced by the science and technology system.”

Of the 16 sector funds, 14 are linked to areas of the economy, such as petroleum, energy, health and biotechnology. Each of them are funded by specific revenue sources. For example, the energy area receives between 0.3% and 0.4% of the sales of utilities in the electricity industry. There are also two funds with a cross-sectional nature: the Verde-Amarelo (Green-Yellow) Fund, which focuses on projects that promote interaction between universities and companies, and the Infrastructure Fund, intended to promote improvements in the infrastructure of scientific institutions. The monies for these two funds come from 20% of the other funds. The original purpose of the funds was to guarantee the stability of the investments, principally by promoting research projects in those industries in which the funds were raised. The guidelines and investment plans for each fund are defined by management committees, composed of representatives of the government, the industry in question, and society. “The funds were designed to promote innovation in management and connect the different actors involved in the implementation of sector policies,” explains Carlos Américo Pacheco, one of the creators of the funds when he was executive secretary of the former Ministry of Science and Technology, between 1999 and 2002. “Over time, the sectorial dimension became less important, with cross-sectional actions taking on greater importance, along with the reallocation of funds to other challenges faced by the science and technology system.”

The cross-sectional actions of the FNDCT were increased slowly, and include support for events, projects not linked to other sector agendas and for topics established in the government’s industrial policy. “The use of money from the funds to supplement needs of the federal S&T system undermined the power of the fund management committees, which began to manage ever smaller amounts,” notes biochemist Hernan Chaimovich, president of the Support Program for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) from 2015 to 2016. In 2016, the management committees did not meet even once. “The funds ended up patching holes in the Ministry’s budget, which was not their original function,” adds economist Fernanda de Negri, of the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA).

One of the main points in the debate on the future of public funding of science involves the improvement of sector funds. Carlos Américo Pacheco believes the funds need to be consolidated into a smaller number than the current one, since some of them, such as the transportation fund and the Inovar-Auto incentive program, involve small amounts. “It is also important to identify new revenues, in addition to linking the funds to the actions and commitments of the regulatory agencies,” he claims.

Regulation of the FNDCT in 2007 consolidated and increased usage, which was already established in laws approved in 2001 and in 2004, of money from the instrument fund managed by FINEP, such as the offer of credit to companies with interest rate equalization, ownership of shares in companies and support for projects by scientific institutions and the private sector. A look at the FNDCT investments in 2016 shows the multiple missions it performs. Out of a total allocated amount of R$1.042 billion, R$342 million was spend on calls for projects defined by the sector fund committees. Another R$309 million was used in instruments such as economic support, guarantees of liquidity for angel investors or equalization of charges, which provides innovative companies access to low-interest resources. Another R$329 million was spent on cross-sectional actions and R$59 million was used to build the Multipurpose Nuclear Reactor.

In spite of the progress in the last decade, use of the FNDCT by companies is declining. In 2016, just R$58.6 million was allocated to support technological development projects–in 2010, this amount was R$526 million. According to Marcos Cintra, in 2017 FINEP will likely only have 50% of the operating resources it had two years ago, and it is not expected to launch any new funding initiatives to research institutions or economic support to companies. The reduction in investments by FINEP and BNDES is a cause of concern for companies. “We expect a recovery of the FINEP budget in the second half, but this will depend on an increase in tax revenues. If this does not happen, the hope is that BNDES will come in and increase support for innovation under reasonable terms,” says Pedro Wongtschowski, Chair of the board of the Industrial Development Study Institute (IEDI) and Vice-chairman of the Board of Directors of Ultrapar. BNDES disbursements on innovation went from 0.8% of the bank’s total investments in 2010 to 4.4% in 2015. In the first half of 2016, that percentage was 3.5%.

State participation

State participation

Another challenge for increasing funding to science is related to the improvement of the financial health of the states. In the past 20 years, several states have established research foundations and assumed commitments to invest certain percentages of tax revenues in science, technology and innovation. “Before the 1990s, only 14 states had foundations. Currently, Roraima is the only state without one,” says Maria Zaira Turchi, president of the Goiás Research Foundation (FAPEG) and of the Brazilian National Council of State Funding Agencies (CONFAP). A recent survey conducted by CONFAP estimated that in 2016, state research foundations invested approximately R$2.5 billion. The amount budgeted for 2017 was R$2.7 billion, but the financial difficulties faced by several states make it unlikely that this level will be achieved. Rio de Janeiro State is experiencing an especially difficult situation. In the midst of a financial crisis in which civil servants’ salaries are not being paid on time, the state government has not been making budgeted transfers of funds to its research foundation, FAPERJ. In São Paulo, the amount budgeted for S&T fell as a result of the decline in tax revenues, but the percentages established in the state constitution were not affected.

In recent years, the foundations became an important source of support, ensuring funding for projects of regional and national interest and signing partnerships for co-funding of programs. An example of these partnerships are the National Institutes of Science and Technology (INCTs), a program jointly administered by the research foundations and the federal government. In the 2014 INCT bid notice, 101 research networks were approved in 16 states. “At those times when transfers of funds from federal agencies, above all from the CNPq were greatly reduced, researchers relied mostly on funding from the state foundations,” says Zaira Turchi.

The discussion on how to better invest funds has been gaining steam. “What is missing is a science, technology and development policy that determines priority areas for investment. Instead of this, Brazil has prepared long wish lists involving all areas of knowledge in the last 20 years,” notes Hernan Chaimovich. “Countries that have established goals and priorities have been able to leverage funds.” Luiz Eugênio Mello is also critical of the difficulty in working with priorities. “There is a tendency in Brazil to spread investments out and answer to as many people as possible. In certain situations, what the country needs is a few well-funded groups that can compete against the best in the world.”

For IPEA’s Fernanda de Negri, Brazilian science needs to be more ambitious. “In countries like the United States, funding for research is tremendously competitive, with a very strong evaluation component. This is still rare in Brazil and things need to change if we want to engage in more high quality science,” she affirms. Although she admits that private funds must be raised, she emphasized that in industrialized countries, it is up to the State to sponsor the lion’s share of funding for science. “These are high risk and basic research investments, and nowhere in the world does the private sector cover this.”

Read: Experiment over

Republish