Heatwaves are becoming more frequent, more intensive, and longer-lasting around the globe; South America and Brazil are no exception. An article published in February this year in the journal Frontiers in Climate provided a series of indicators that measure the scale of this type of extreme event in Brazil, Paraguay, northeastern Argentina, and southern Bolivia. Based on Brazilian Meteorological Service data, the researchers calculated the incidence, potency, and duration of heatwaves across ten cities, five of which in Brazil (Manaus, Rio Branco, Brasília, Cuiabá, and São Paulo) between 1979 and 2023. In all the locations this type of event trended towards its highest point in 2023, the second warmest year on the planet since the preindustrial mid-nineteenth century. For many days, temperatures peaked at between 35 and 40 degrees Celsius (ºC).

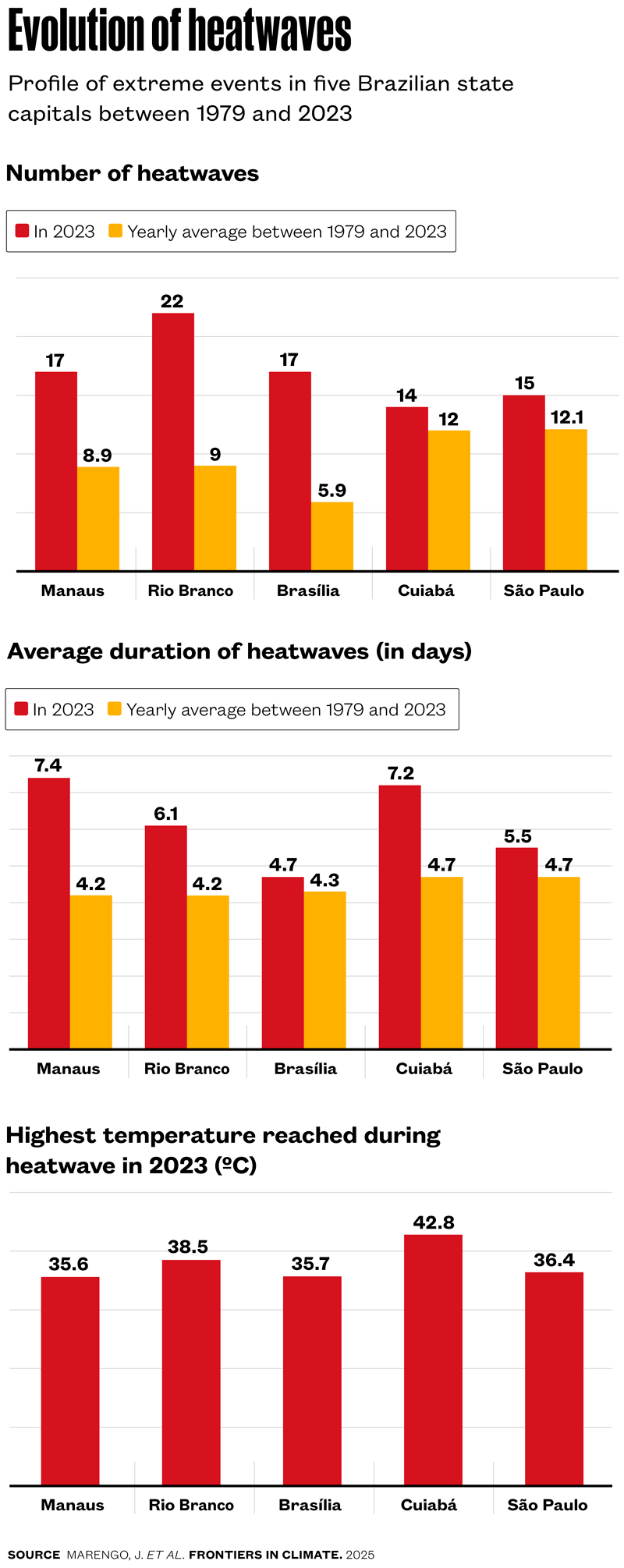

Of the Brazilian cities analyzed during the study, Manaus, Rio Branco, and Brasília presented indicators with the most significant increase in terms of climate phenomenon incidence. In the state capitals of Amazonas and Acre respectively, there were 17 and 22 heatwaves in 2023, practically double the yearly average recorded over the 45 years of the study. In the federal capital Brasília, the frequency of these persistent high temperatures almost tripled. There were 17 heatwaves the year before, against a background average of 5.9 events per year. In 2023, there were 14 heatwaves in Cuiabá, and 15 in São Paulo, respectively two and three more events against the annual average observed over almost half a century of data gathered by the study (see table of Brazilian cities). In four of the other five South American cities (the Argentine Las Lomitas, the Paraguayan Mariscal Estigarribia, and the Bolivian San Ignacio de Velasco and San Jose de Chiquitos), the incidence of heatwaves was even higher, with at least 23 events in 2023.

“Heatwaves are a natural phenomenon, but climate change primarily increases their intensity and duration,” says the article’s lead author José Marengo, of the Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring (CEMADEN). In 2023, prolonged extreme heat events extended for a minimum of 4.7 days in Brasília and 7.4 in Manaus, exceeding background averages for the two cities, formerly equal at 4.2 days. Marengo is concluding a similar study, this one with data from 2024—the hottest year in recent history—and as expected, the results are headed in the same direction.

The sixth report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), published in 2021, indicates that the intensity and frequency of hotter days, including heatwaves, have been increasing since the 1950s on a global scale (days of extreme cold are decreasing). This is a very clear trend around more than 80% of the planet.

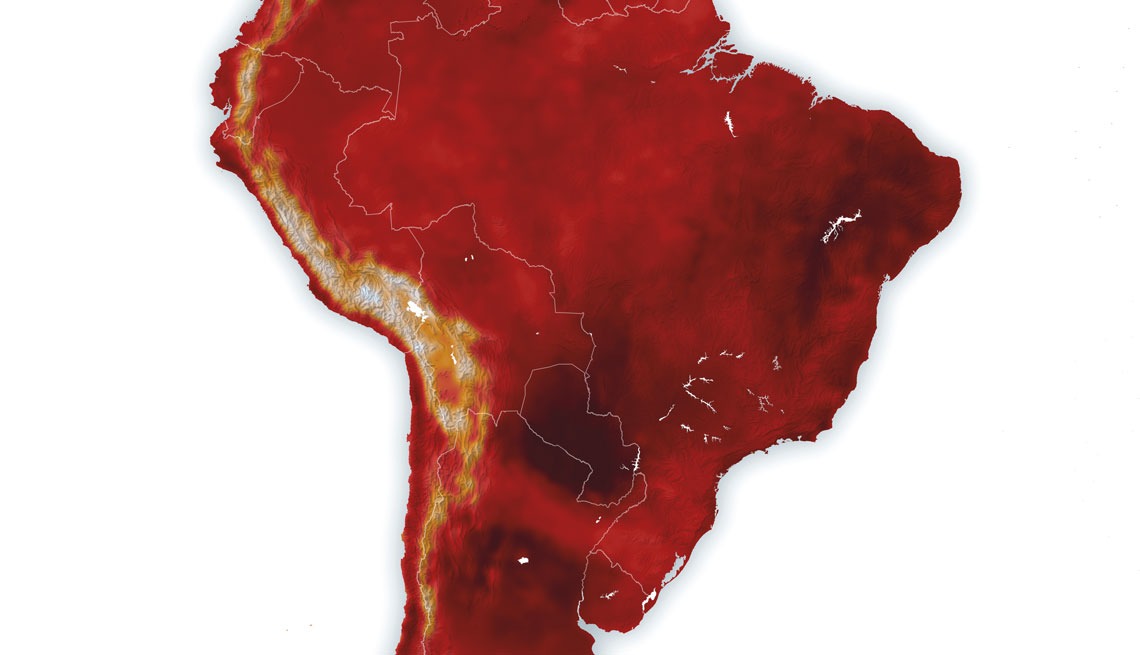

Recent studies suggest that South America is among the most susceptible regions to these increasing extreme heat events; for example, a study published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment in April 2024 demonstrates that the continent, particularly its northcentral region, recorded more heatwaves in 2023 than any other area on Earth, with between 110 and 150 days’ exposure to heatwaves—more than three times the yearly average for the period between 1990 and 2020. Africa was the second continent with most heatwaves the year before last.

According to the study, during those consecutive days of intense heat in South America in 2023, temperatures reached between 0.5 ºC and 1 ºC above that expected for Peru, northern Bolivia, and Brazil. The increase was higher in Chile, southern Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina—between 1 ºC and 3 ºC. “Brazilian regions most exposed to heatwaves, including in the winter and early spring, were Amazonia, part of the Pantanal (wetlands region), and the Southeast,” says climatologist Renata Libonati, coordinator of the Environmental Satellite Applications Laboratory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s Department of Meteorology (LASA-UFRJ). “Things were even worse in 2024.” The Brazilian was one of the article’s authors alongside researchers from other continents, and is currently finalizing a new study with the same international team, using data from 2024.

Pablo Porciuncula / AFP via Getty ImagesPublic water distribution in Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro, during the heatwave in February this yearPablo Porciuncula / AFP via Getty Images

One very hot day, even when exceeding expected temperatures, does not constitute a heatwave. Although there is no absolute consensus about how to define this type of extreme phenomenon, one piece of common ground among all approaches is that a heatwave must present temperatures far in excess of the historical background, or other reference value, for at least three consecutive days. Some definitions are stricter on the question of duration, adopting five consecutive days of very high temperatures as the minimum required to characterize the phenomenon.

Several scientific studies, such as that featured in Frontiers in Climate, apply the concept of a heatwave comprising at least three consecutive days with a maximum temperature exceeding 90% of background records over a 30-year period at a location. Sometimes the daily minimum temperature is taken into account to classify this type of extreme event. “Under this definition there is no magic number by which we can say that there is a heatwave whenever the temperature remains, for example, 4 °C above a certain value,” says Marengo.

The Brazilian weather and climate services tend to apply a different heatwave concept than that used in scientific studies. “We adopt the standard of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), where a heatwave is defined by its persistence; in other words, a heatwave occurs when maximum daily temperatures exceed the monthly average by at least 5 °C for a minimum of five consecutive days,” explains meteorologist Danielle Barros Ferreira, of the Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET). “For example, the average maximum temperature for February in the city of São Paulo is 29 ºC. Therefore, for an event to be a heatwave, maximum temperatures need to reach 34 ºC or more for at least five days.” The average maximum temperature is calculated based on what is known as the climatological normal, a period of 30 years considered as representative of the recent atmospheric conditions in a region. In the case of INMET, which only started calculating heatwaves in January 2023, the current climatological normal covers the period between 1991 and 2020.

The different definitions of the heatwave concept explain the divergences in numbers between studies aimed at trying to capture the dimensions of these extreme events, and at times hamper the comparison of their results. The lack of longer background series and gaps in the existing data also make it difficult to accurately determine the frequency and intensity of this phenomenon in the more distant past. One of the few studies to analyze heatwaves in Brazil over a longer period—60 years—was published in late 2023 by the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The study used a similar methodology to that described in the article coordinated by Marengo, but defined heatwave as a longer period, with at least six consecutive days at higher maximum temperatures.

Using data from 1,252 weather stations across Brazil, the INPE study concluded that between 1961 and 1990 there were an average of 7 days per year with heatwaves in the country. This number rose to 52 days a year between 2011 and 2020. “Over recent decades there has been a gradual increase in heatwaves in practically all of Brazil,” says climatologist Lincoln Muniz Alves, of INPE, one of the study’s authors. “Only the southern region, the southern half of São Paulo State, and the south of the state of Mato Grosso do Sul did not present this trend.”

Paulo Pinto / Agência BrasilThe welcome fountain on a hot day in November 2023 in Vale do Anhangabaú, São PauloPaulo Pinto / Agência Brasil

The central mechanism that generates higher-than-expected temperatures over several days is known as atmospheric blocking. A high-pressure system pushes air downwards and hovers for days over a region, completely altering the local atmospheric circulation. The anomaly prevents cold fronts, which normally bring rains, from coming in. “A warm air bubble forms over the area,” says meteorologist Tércio Ambrizzi, of the Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of São Paulo (IAG-USP). “Under these conditions it’s common to see what we call compound extreme weather events, with a heatwave associated to prolonged drought.”

Global warming increases the occurrence of atmospheric blocking in certain regions of the planet, partly explaining the dissemination of heatwaves. Regional factors also come into play, such as the El Niño phenomenon: a natural, periodic climate oscillation characterized by the abnormal warming of surface waters in the east-central area of the Pacific Ocean. El Niño raises temperatures in South America and alters the rainfall pattern. When it arrived in full force in 2023, the phenomenon was indicated as one of the causes of the long droughts and extreme heat in Amazonia that year. The degree to which a region is urbanized also influences the occurrence of extreme events linked to high temperatures. Cities of concrete, cement, and asphalt are hotter than rural zones and regions interspersed with green areas, and this is known as the heat island effect.

Lengthy episodes of extremely high temperatures do not just cause thermal discomfort—they also bring about adverse economic and social effects. At the beginning of this year, for example, classes in schools were suspended for days in Porto Alegre and Rio de Janeiro due to persistent temperatures around 40 ºC. “We are not prepared to deal with heatwaves, even more so being a tropical country where it seems natural or normal to have hot days,” comments Libonati. “But heatwaves act silently and can cause deaths, primarily in children, the elderly, and pregnant women.”

This situation is not expected to change anytime soon. The last 10 years, from 2015 to 2024, were the 10 hottest since systematic measurements of average global temperatures began in the mid-nineteenth century. Throughout last year global warming, for the first time in recent history, was 1.5 ºC higher than the reference value for the preindustrial period, and even more intense heatwaves are therefore expected going forward. “We must limit global warming and minimize the effects of this situation as much as possible,” says Marengo.

The story above was published with the title “More frequent, intensive, and longer-lasting” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Project

INCT for Climate Change (nº 14/50848-9); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Program FAPESP Research Program on Global Climate Change (PFPMCG); Principal Investigator José Antônio Marengo Orsini (CEMADEN); Investment R$5,300,662.72.

Scientific articles

MARENGO, J. A. et al. Climatological patterns of heatwaves during winter and spring 2023 and trends for the period 1979–2023 in central South America. Frontiers in Climate. Feb. 12, 2025.

PERKINS-KIRKPATRICK S. et al. Extreme terrestrial heat in 2023. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. Apr. 4, 2024.

Republish