In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) established three targets as part of the End TB Strategy: by 2035, achieve a 90% reduction in the number of new cases (the incidence rate) compared to those recorded in 2015 and a 95% decline in deaths. Another target is ensuring that no families lose more than 20% of their annual income when a family member falls ill, the so-called catastrophic cost of the disease.

Brazil has nothing to celebrate when it comes to these three targets. According to data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, at least 81,539 new cases were diagnosed in Brazil in 2022 and a total of 5,824 deaths were recorded, a regression compared to 2015, when there were 69,809 cases and 4,610 deaths. With free diagnosis and treatment provided by the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), Brazil was expected to perform well on the third target, at the very least. A study published in December of 2023 in the science journal PLOS ONE, however, indicates that this is not the case: almost half of patients’ families still report losing more than 20% of their annual income when one of their members falls ill with an episode of tuberculosis.

Caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, tuberculosis is contagious and chronic. Most of the time, the airborne microorganism settles in the lungs and is eliminated by the immune system. A small amount of these bacteria, however, can invade the defense cells and remain dormant for years, until, at a time when the immune system is weakened, they proliferate again and cause the most common symptoms, such as coughing (usually with discharge), fatigue, low fever, chest pain, and shortness of breath. In Brazil, the SUS offers free diagnosis, performed using a chest X-ray, microscopy exams, or molecular testing with bacteria cultures extracted from sputum. The SUS also offers free treatment consisting of a combination of antibiotics administered for at least six months. But there are other costs that fall on families, such as travel and food costs during visits to outpatient clinics and hospitals, as well as reduced income due to time off from work or loss of employment.

To measure this burden placed on families, the team led by nurse Ethel Noia Maciel, a professor at the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES) and current Secretary of Health and Environmental Surveillance (SVSA) for the Ministry of Health, interviewed 603 people undergoing treatment for tuberculosis between September of 2019 and April of 2021. The patients were from 34 cities, selected through a lottery system that sought to ensure that the cities were statistically representative in terms of the number of cases. The costs declared by the patients were totaled and then divided by the annual household income. In the study, 65 participants had tuberculosis caused by drug-resistant microorganisms and 538 had drug-susceptible tuberculosis.

In 48% of the families, direct medical costs (extra consultations or exams), direct nonmedical costs (transportation, food, lodging, dietary supplements, among others), and indirect costs (loss of income) comprised over 20% of their annual income—this means that they incurred catastrophic costs, according to WHO criteria. In cases where the infection was caused by drug-resistant bacteria, which requires longer treatment and follow-up, the proportion of families who had to deal with catastrophic costs rose to 78.5%.

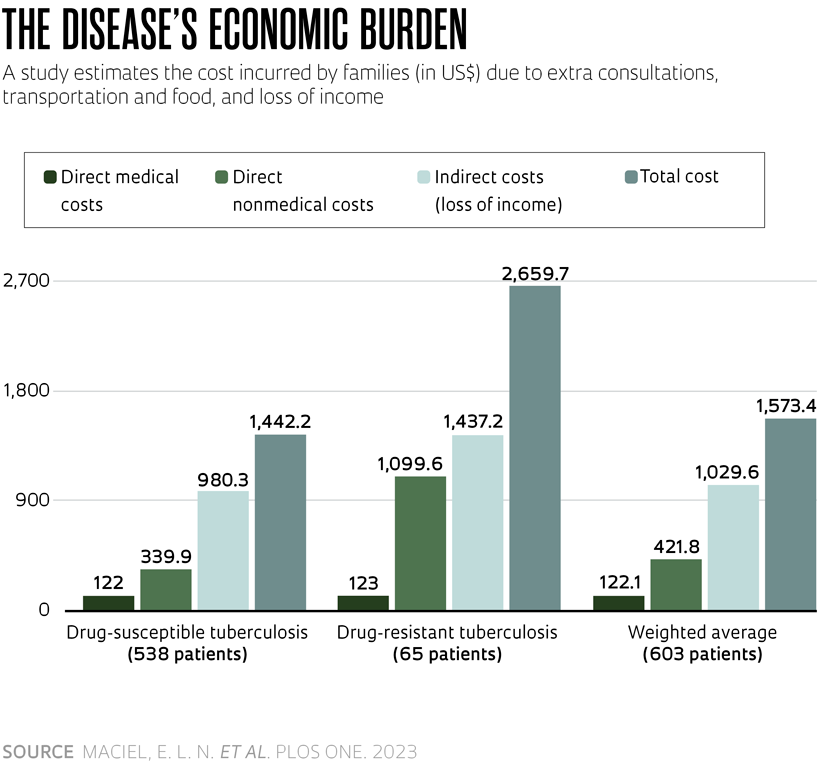

The extra annual expenses amounted to an average of R$8,118.74 (equivalent to US$1,573.40 at the September 2021 exchange rate), almost seven times the minimum wage at the time. The cost was R$7,441.75 (US$1,442.20) for drug-susceptible infections and jumped to R$13,724 (US$2,659.70) for drug-resistant infections. In both situations, more than 90% of the burden was due to nonmedical costs and indirect costs. On average, nonmedical costs accounted for US$339.90 in drug-susceptible tuberculosis and US$1,099.60 in drug-resistant tuberculosis. Indirect costs (loss of income) accounted for an average of US$980.30 in the first case and US$1,437.20 in the latter (see graph).