In environments weakened by the devaluation of the teaching profession and the deterioration of school infrastructure, where students suffer psychological distress and conflict management policies are scarce or nonexistent, hate speech spread via online communities and social media can have a devastating effect. The issue is considered central to the rise in extreme attacks that occurred in Brazil between 2022 and 2023.

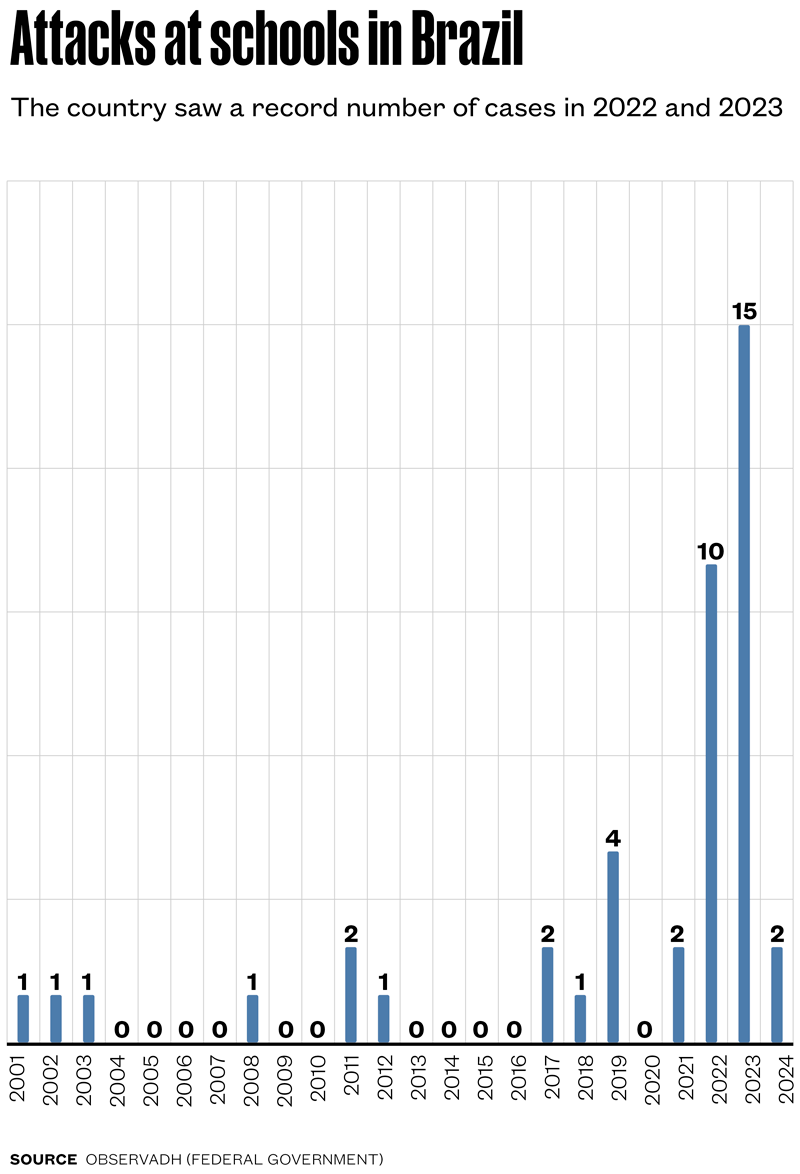

The federal government’s National Human Rights Observatory (ObservaDH) estimates that there were 43 such attacks in Brazil between 2001 and 2024, resulting in 168 victims, of which 47 died and 115 were injured (see graph). Six attackers also died. Firearms were used in 19 of the attacks and all of the perpetrators were men. Police investigations found that many of them were influenced by online hate speech. “Extremist communities and forums have been identified as spaces of radicalization where young people are encouraged to plan and carry out acts of extreme violence,” says sociologist Daniel Cara of the University of São Paulo (USP), who led the study “Attack on schools in Brazil: Analysis of the phenomenon and recommendations for government action,” carried out by a working group established by the MEC and published at the end of 2023.

Cara points out that shootings have been recorded at schools in the USA since the nineteenth century. In Brazil, the attack on a school in Realengo, Rio de Janeiro, in 2011 is considered the beginning of a new phase of extreme violence, followed by the tragedy that occurred in Suzano, São Paulo, in 2019. “These attacks were carried out by students and former students in response to resentment, failures, and violence experienced in life and in the school community. Many are copycat crimes based on previous attacks,” explains the researcher.

In 2019, psychologist and researcher Marilene Proença Rebello de Souza was serving as director of USP’s Psychology Institute when she received an urgent call from the university’s dean at the time, Vahan Agopyan. He tasked her with coordinating a group of 22 professionals, including specialists in emergencies and school psychology, to provide emergency assistance to the school where the attack took place in Suzano. The team began work on the day of the attack, which affected the entire city. According to Souza, more than 1,500 people sought health services in the municipality in the period following the tragedy due to the psychological impact of the event. “I have been researching violence and education since 1985 and I have never experienced anything like it. Since then, this new form of aggression has become a priority in my research,” says the USP psychologist, who participated in a national survey on violence and discrimination in schools between 2016 and 2018, conducted at the request of the MEC.

In her opinion, the return of face-to-face classes after the COVID-19 pandemic came with additional challenges in the school environment, including a need to strengthen the sense of belonging and coexistence between students and school staff. Souza is currently director of the Science Center for the Development of Basic Education: Learning and Coexistence in Schools, which was approved in 2024 and funded by FAPESP and SEDUC-SP and aims to support the formulation of public policies on the issue.

The absence of a national program designed to improve the school climate is highlighted by researchers as one of the obstacles to tackling violence in the country. “Addressing the discrimination and prejudices that lead to violence is not part of the school curriculum and the topic only appears on the agenda of education departments when there are extreme cases,” points out Souza. She notes that Brazil has a National Common Curriculum to establish mandatory content for basic education, but it does not have a curricular matrix focused on coexistence in schools. “The task of educating students as citizens, which is centered on dialogue, participation, and guaranteeing rights, must not be treated as secondary,” argues the researcher.

Another problem is growing access to firearms. Psychologist Danielle Tsuchida Bendazzoli, project coordinator at the Sou da Paz Institute, says that attacks at schools in Brazil have worsened since 2019, a period that coincides with the relaxation of rules on the possession and carrying of firearms. Data collected by the institute show that between 2019 and 2022, the number of registered weapons in Brazil increased from 695,000 to 1.9 million. “When firearms are used in this type of attack, the number of victims is on average three times higher,” says the psychologist. The institute’s 2023 report “Raio x de 20 anos de ataques às escolas no Brasil” (“Overview of 20 years of attacks at schools in Brazil”) showed that in 60% of cases in which firearms were involved, they were obtained inside the perpetrator’ own home.

Increase in violent attacks coincides with growing presence of extremist communities online

Telma Pileggi Vinha, a pedagogue from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), analyzed extreme violence recorded in the country and identified that the majority of aggressors were aged under 18 when they committed the attacks. “This shows how vulnerable people in this age group are to becoming involved in extreme violence,” she points out. According to Vinha, most attackers had few friends and many were part of online hate communities. “Up until November 2024, all perpetrators of these attacks in Brazil had been male. In December of that year, the first case involving a young woman was recorded,” she reports. Some of the aggressors also showed signs of mental illness—sometimes undiagnosed or untreated—and all had suffered negative experiences at school, such as humiliation, exclusion, and bullying. She recalls a post made by one attacker on a social network, in which the young man said that he enjoyed school until he started to suffer systematic bullying from his classmates. “The boy wrote that he had no one to help him and that he intended to carry out the attack as a way to make everyone aware of his suffering,” explains the researcher.

From 2015 to 2018, Vinha led a study at 10 public schools in Campinas and Paulínia, both in the state of São Paulo, which included conflict management training for teachers, as well as measures and analyses of their impacts on relationships within the schools. “Although the results were positive in the short term, all progress was lost a year and a half later because the initiatives were not formally adopted and many teachers changed schools,” she explains. It is therefore important, she emphasizes, for programs to be implemented on a large scale and to promote sustainable, long-term transformations.

Thaís Luz, the MEC’s general coordinator for monitoring and tackling violence in schools, believes episodes of extreme violence are part of a broader rise in extremism in Brazil and a lack of control over hate speech and discrimination, which are disseminated through digital media. “The occurrence of violent attacks in schools has increased significantly since 2019, coinciding with a time when extremist communities, previously restricted to the deep web, have begun to operate openly on social media,” he states. Cara, from USP, explains that online forums that promote hate speech groom teenagers through virtual interactions and strategies that combine humor and violent language.

Valentina Fraiz

Valentina Fraiz

In response to the rise in school violence, the federal government established the National System for Monitoring and Tackling Violence in Schools through Decree No. 12,006 of April 2024. The system offers guidelines for prevention and action in cases of extreme violence. Last December, the MEC launched the Escola que Protege (schools that protect) program to strengthen educational institutions’ ability to prevent and respond to violence. “The program provides ongoing training to educators, creates spaces for democratic coexistence, combats bullying and discrimination, and develops monitoring and communication strategies,” Cara says. The initiative links the MEC with bodies such as the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship, and the Federal Police.

Psychologist Antônio Álvaro Soares Zuin of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), who has been studying the relationship between violence, technology, and education for over a decade, also warns about the impact of the internet on the school environment. He explains that when someone is bullied, the violence is physical and psychological, with the victim being a constant target of aggression. But when it comes to cyberbullying, a single post can remain online indefinitely. “Even if it is removed by court order, it can later be reposted,” he says.

Zuin studied more than 100 schools in Brazil and abroad, finding that students often film and share videos of teachers without their consent, frequently accompanied by derogatory comments. This practice, which began with communities on the social network Orkut in the 2000s, was exacerbated by the popularization of smartphones from 2007 onwards and then by the migration to social networks with even greater reach. In the past, he says, cyberbullying posts were restricted to forums and closed groups, but with the spread of smartphones, offensive videos recorded at school began to be shared openly, with some reaching thousands of views. According to the researcher, this practice is often used as a form of revenge against teachers who have disciplined students. “Amid so many opportunities for distraction, which is typical of digital culture, students use their cell phones to take revenge by cyberbullying their teachers, the very figures responsible for ensuring their attention remains focused on their studies,” he explains.

Law No. 14,811 of 2024 establishes bullying and cyberbullying as crimes within a new legal category, expanding the scope of situations that can be classified as such and defining criteria for what may be considered systematic intimidation. However, jurist Lucas Catib de Laurentiis of the Pontifical Catholic University of Campinas points out that it is natural for young people to sometimes be uncivil and to challenge norms and authorities as they develop their personalities—as long as this does not involve crimes such as racism and homophobia. “With this new law, a simple discussion between students can result in criminal proceedings, creating an environment of fear and self-censorship. We need to combat violence, but we also need to differentiate between behavior that should be prosecuted and behavior that should not, to preserve a climate that enables the construction of each student’s identity,” concludes the jurist, who is carrying out research funded by FAPESP on the prevention of violence and attacks in schools in the city of Campinas.

The story above was published with the title “Hostile environment” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Projects

1. Science Center for the Development of Basic Education: Lessons Learned and School Coexistence (nº 24/01116-7); Grant Mechanism Science Centers for Development; Principal Investigator Marilene Proença Rebello de Souza (USP); Investment R$874,049.92.

2. Project Aegis: Violence, education, and surveillance in schools in the municipality of Campinas (nº 23/10005-1) Grant Mechanism Research in Public Policies; Principal Investigator Lucas Catib de Laurentiis (PUC-Campinas); Investment R$295,797.63.

Reports

BACCHETTO, J. G. Construindo um indicador sobre ocorrência de violência nas escolas no Saeb. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira; 2024.

CARA, D. Ataques às escolas no Brasil: Análise do fenômeno e recomendações para a ação governamental. Brasília: Grupo de Trabalho de Especialistas em Violência nas Escolas – MEC. 2023.

CERQUEIRA, D. & BUENO, S. Atlas da violência 2,024. Brasília: IPEA, FBSP. 2024.

Raio x de 20 anos de ataques às escolas no Brasil 2002-2023. Instituto Sou da Paz. 2023.

Violência e preconceitos na escola: Contribuições da psicologia. Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso (UFMT) e Fórum de Entidades Nacionais da Psicologia Brasileira (eds.). Brasília: Conselho Federal de Psicologia, 2018.

Book

VINHA, T. Ataques de violência extrema em escolas no Brasil: Causas e caminhos. São Paulo: D3e, 2023.

Republish