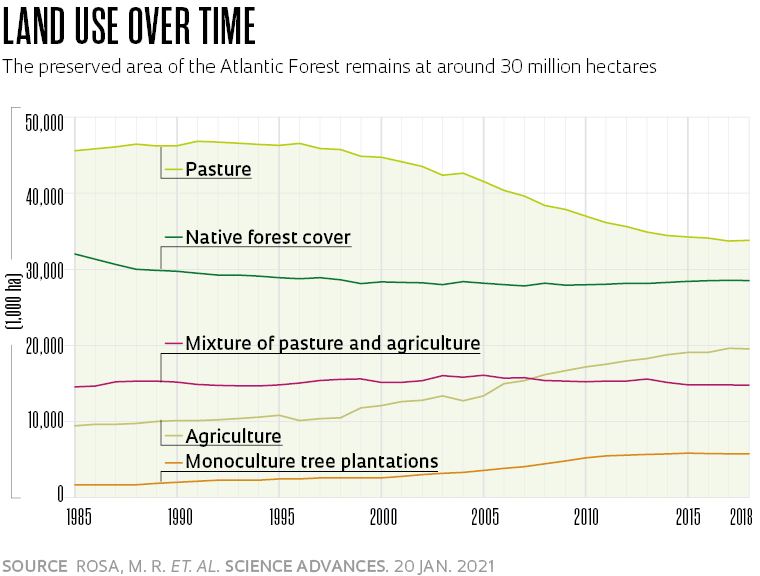

Since the late 1980s, native areas of the Atlantic Forest, one of the most threatened biomes in Brazil, have remained relatively stable in size. Its total area varies between 28 million and 30 million hectares (ha), about 28% of its original size. Since 2005, native forest areas grew at a slightly higher rate than they were lost—usually cut down to make way for agriculture and livestock farming. But what sounds like good news is actually hiding a concerning situation: old forests continue to be deforested at a worrying rate, replaced by younger vegetation in a progressive rejuvenation of the Atlantic Forest that has a harmful impact on biodiversity and ecosystem services (the benefits offered by nature). This is the main conclusion of an article published in the journal Science Advances in January.

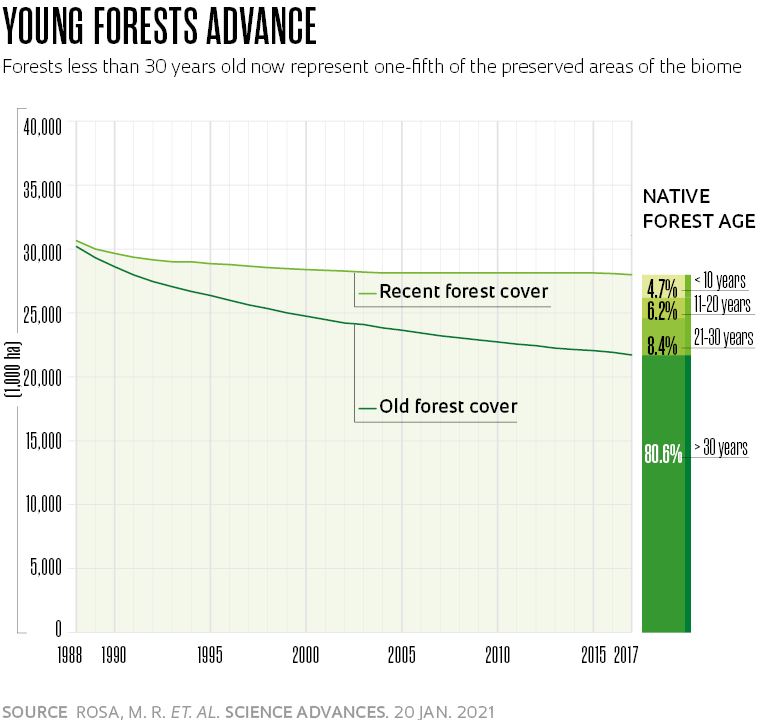

By convention, areas of Atlantic Forest that existed in 1985, when annual mapping of the biome began, are considered old. Since then, old forest has been losing ground. Currently, 80% of native forests are composed of vegetation over 30 years old, while 20% are less than three decades old (see graph on page 66). Although about 80% of tree species regrow in recovered areas within 20 years, the time it takes to completely restore flora biodiversity is estimated at more than a century.

Old areas of the Atlantic Forest are irreplaceable, since many species of animals, plants, and micro-organisms rely on these more mature and untouched habitats to survive. “More biodiverse forests are better at regulating the climate, providing water, and supporting agricultural production through pollination and pest control,” says biologist Jean Paul Metzger, from the Institute of Biosciences (IB) at the University of São Paulo (USP), leader of the group that wrote the article. “Unlike mature forests, which store a lot of carbon and biodiversity, forests under restoration take many years or even decades to provide similar benefits. In many cases, they never reach that level because they are degraded during the process by fires, invasions of exotic species, and other complications. What is lost cannot always be recovered,” warns engineer and agronomist Pedro Brancalion, from the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ) at USP in Piracicaba, coauthor of the article in Science Advances.

“The idea that after centuries of continuous deforestation, the Atlantic Forest is gaining more ground than it is losing, is a half truth,” says geographer Marcos Rosa, technical coordinator of the MapBiomas project and lead author of the paper. MapBiomas is run by Observatório do Clima (“The climate observatory”), a non-governmental organization (NGO) that brings together universities, technology companies, and other Brazilian organizations, dedicated to mapping land use in the country. “We thought the oldest forests in the biome were already well protected and the major challenge for the Atlantic Forest was restoration. But we have seen that conservation remains a problem, and that restoration needs to go hand in hand with protecting older forests,” explains Brancalion.

The article is part of the PhD thesis defended by Rosa at USP in February this year and is linked to a thematic project jointly funded by FAPESP and the Dutch Research Council (NWO). Brancalion is the Brazilian coordinator of the initiative and Frans Bongers, from Wageningen University, leads the project in the Netherlands.

SOS Mata Atlântica

Degraded area of the biome in Santa Catarina, suffering loss of vegetationSOS Mata AtlânticaAccording to Rosa, although the percentage of native vegetation in the Atlantic Forest increased, comparisons between satellite images taken in 1990 and 2017 revealed a high rate of deforestation in older forests, especially in the north of Minas Gerais, at the border with Bahia, and in the south of Paraná and Santa Catarina. In the same period, native forests grew, especially in the states of Paraná and São Paulo, the south of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo, along the coast of Pernambuco and Paraíba, and in the mountainous region of Rio de Janeiro. But this growth does not fully compensate for the losses.

For computer scientist Milton Cezar Ribeiro, head of the Spatial Ecology and Conservation Laboratory at São Paulo State University (UNESP) Rio Claro campus, the most important thing is not knowing how much forest there is, but what state it is in. He emphasises that the ability to maintain or restore biodiversity depends largely on the conditions of the area. “More isolated forest fragments suffer greater border impacts,” says Ribeiro, who did not participate in the study. “The boundary between the edge of the forest fragment and human activities, such as livestock farming and agriculture, creates an environment that is unfavorable to fauna maintenance and ecological processes.”

The new research also found that fragmentation of the Atlantic Forest is increasing. According to the study, due to changes in native vegetation cover and its spatial distribution, areas of forest were found to have become more isolated in 36.4% of the biome’s remaining area. For Ribeiro, the study presents a level of detail that has never before been achieved. “Part of this is an increase in vegetation in some regions and part is the result of a finer mapping process that was able to include smaller areas,” highlights the computer scientist. “Until now, we didn’t know what the areas of Atlantic Forest were like and how they have changed over time.”

This level of detail was achieved by analyzing material compiled and made available by MapBiomas: more than 50,000 satellite images provided free of charge by the Landsat satellites, operated by NASA and the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Covering a period of more than 30 years (from 1985 to 2019), the images have a resolution of 30 meters and were classified by a machine learning algorithm. To perform this vegetation mapping and classification process, Rosa, a specialist in geoprocessing, relied on the collaboration of different MapBiomas members. “The idea of writing a thesis in parallel to the MapBiomas initiative was born of a desire to improve the scientific basis of the project,” he says.

The study is the first result of the thematic project led by Brancalion. The initiative’s objective is to map all forests that have emerged in the state of São Paulo over the last three decades, whether through restoration projects or natural regeneration, and to evaluate the ecosystem services they provide, such as their capacity to store carbon, preserve biodiversity, and promote water infiltration in the soil. “We are going to study 1,000 parcels distributed throughout the state, each measuring 900 square meters [0.09 ha]. Even with the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, we have already analyzed 350 of these parcels,” reports the ESALQ researcher.

The project has about 100 members dedicated to this task, of which a fifth are working in the field. During less severe periods of the pandemic, the researchers work in teams of five, who all take COVID-19 PCR tests before traveling. These groups remain in the field for 15 days, ensuring to follow protective measures against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. “So far, no members of the field teams have been infected, but we have stopped all face-to-face activities now that the state of São Paulo has returned to such a critical phase of the pandemic,” says Brancalion. “The information from this mapping process opens new possibilities for using data on deforestation and regeneration dynamics over a 30-year period,” says Metzger. “We have at least five or six more articles to write and publish, analyzing this MapBiomas data more deeply.”

Less biomass

While the article in Science Advances warns of the decrease in old areas of the Atlantic Forest and the consequent risks to biodiversity, another Brazilian study, published in Nature Communications in December 2020, quantifies the extent of this loss: about 85% of forest fragments in the biome show a reduction in biomass and tree species richness. The forest fragments are less dense and have less tree biodiversity.

According to the study, led by ecologist Renato Augusto Ferreira de Lima, who is currently doing a postdoctoral fellowship at IB-USP and is a researcher associated with the thematic project, the areas of vegetation under analysis have 25–32% less biomass and 23–31% fewer species. The estimate is based on information from 1,819 field studies by various research groups and shared on the Neotropical Tree Communities database (TreeCo), created by Lima in 2014.

Project

Understanding restored forests for the benefit of people and nature – NewFor (no. 18/18416-2); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; NWO Agreement; Principal Investigator Pedro Brancalion (USP); Investment R$1,539,356.27.

Scientific articles

ROSA, M. R. et al. Hidden destruction of older forests threatens Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and challenges restoration programs. Science Advances. Jan. 20, 2021.

LIMA, R. A. F. et al. The erosion of biodiversity and biomass in the Atlantic Forest biodiversity hotspot. Nature Communications. Dec. 11, 2020.