The Center for Women’s Comprehensive Healthcare at the University of Campinas (CAISM-UNICAMP) was the scene of an unprecedented experimental procedure at the end of April. For the first time, surgeons used skin from the Nile tilapia (Oreochromis nicoticus) to reconstruct the vaginal canal of a transgender patient who had, years ago, undergone unsuccessful sexual reassignment surgery while transitioning from male to female. The procedure is the result of extensive research on the use of tilapia skin for medical purposes initiated four years ago at the Center for Drug Research and Development of the Federal University of Ceará (NPDM-UFC), in partnership with the Burn Victim Support Institute (IAQ) in Fortaleza.

The trans patient, whose identity was protected, sought out the team of surgeon Leonardo Bezerra, from the Department of Maternal and Child Health at UFC. The patient had learned of the positive results of the use of fish skin in the vaginal reconstructions—known as neovaginas—of 10 women affected with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome, a rare congenital disorder which causes them to be born with an underdeveloped or absent vaginal canal. The same team had already successfully operated on a woman whose vagina needed reconstruction because of damage from gynecological cancer.

“The other option the trans patient had was to have a bowel segment autograft, an extremely aggressive, time-consuming surgery with long-term complications,” says Bezerra. “Using tilapia skin allows for a simpler, faster, and less invasive operation. The epithelium from tilapia skin acts as a framework and support for the development of the vaginal epithelium, with appropriate elasticity, size, and functionality.”

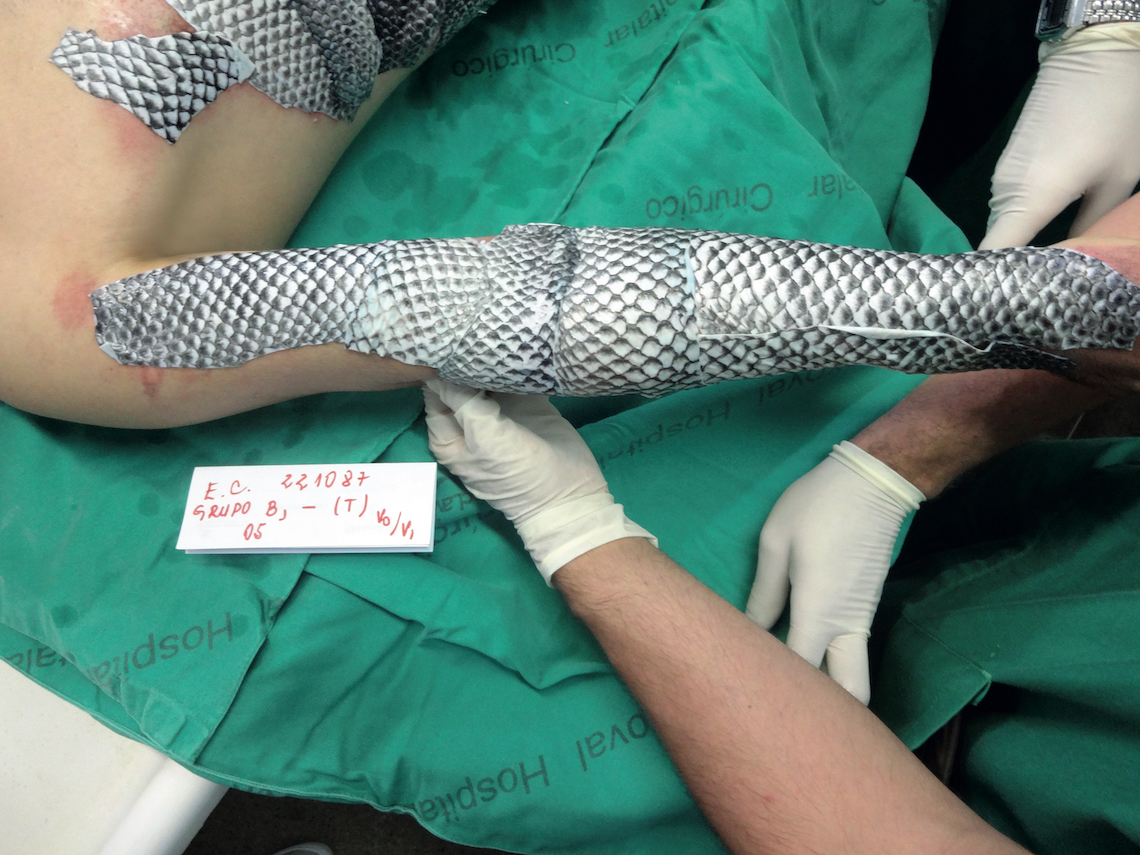

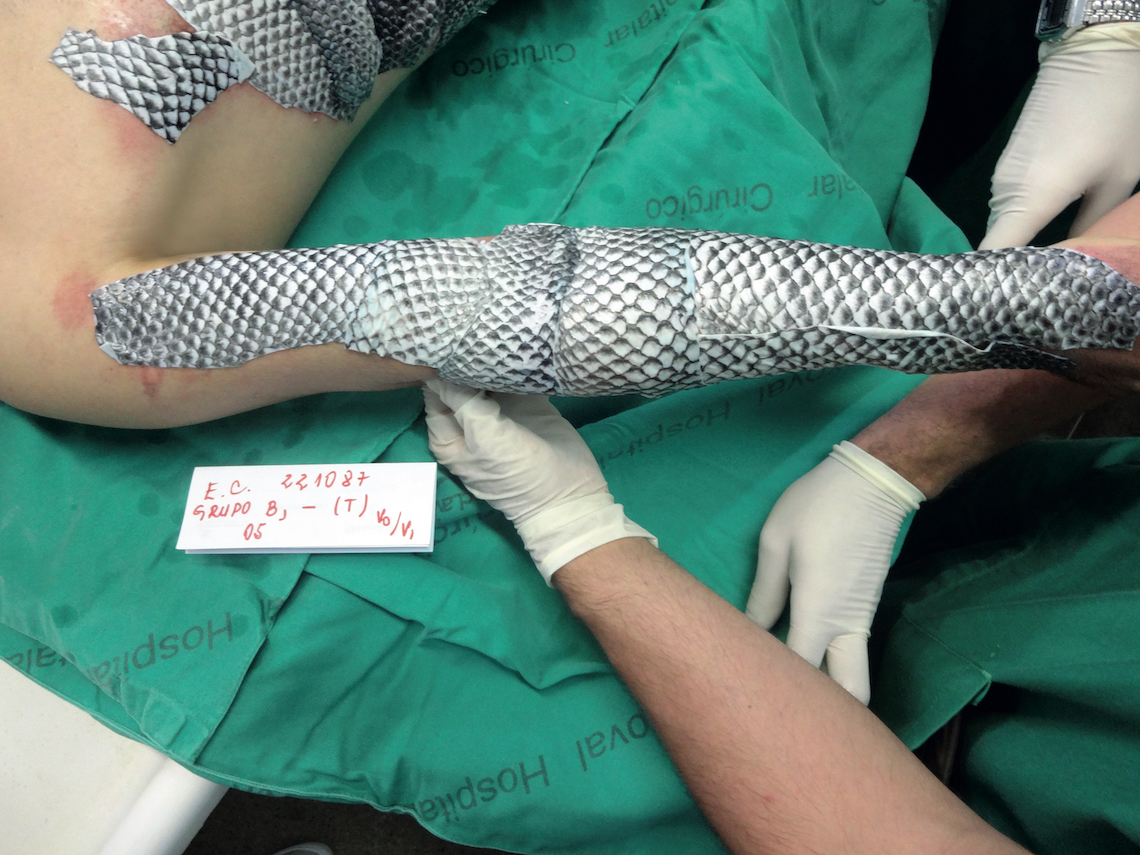

Both in the surgery performed at UNICAMP, and those performed at NPDM-UFC, the patients—women with MRKH syndrome—kept an acrylic mold wrapped with tilapia skin inside the vaginal canal for about a week. Afterwards, the prosthesis was removed and the fish skin left in place. “The collagen [from the tilapia skin] is gradually destroyed, its molecules are ‘broken’ and the animal’s skin is incorporated into the tissue. This causes cells present in the vaginal canal to differentiate into others, forming the vaginal epithelium,” explains doctor Manoel Odorico de Moraes, NPDM-UFC coordinator and a professor at the UFC School of Medicine. There is no need to medicate patients with immunosuppressive drugs because the biological material is not being placed inside the abdominal cavity, but in the vagina, which is an extension of human skin. “To date there hasn’t been one case of rejection,” says Moraes.

Edmar Maciel

Fish skin dressing is used to treat burn patient

Edmar Maciel The Ceará team has been widely sought out by transgender patients who have undergone male-to-female sexual reassignment surgery with unsatisfactory results via the standard technique, which uses the skin of the penis itself to construct the neovagina. “What happens is that before surgery they have hormone therapy so the body will acquire female characteristics, which reduces the size of the penis. The treatment leaves too little penile skin and the vagina is barely functional,” says Leonardo Bezerra, from the UFC School of Medicine.

Research network

Since 2015, Moraes has been leading the tilapia skin research, along with plastic surgeon Edmar Maciel, the president of IAQ. The study began when they championed an original idea by plastic surgeon Marcelo Borges, a professor at the Olinda Medical School in Pernambuco State. After reading a report on artisanal crafts made from tilapia skin, Borges figured he could use the material to treat burns, since it’s very rich in collagen and is an inexpensive item that is generally discarded by the fishing industry. The use of biological dressings for treating wounds and burns is not new, globally. In addition to human skin itself, made available through skin banks, pigskin is also used, among other materials.

Today, the line of research on tilapia skin has 189 collaborators in seven Brazilian states and in six other countries: the United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico. “They are all coordinated by our group,” says Maciel. The biological material is the object of 43 research projects being conducted in Brazil and the other countries.

In addition to the successful treatment of burns and vaginal reconstruction, other uses for the material are being studied in dental and veterinary procedures. “So far we have filed five patent applications in Brazil and abroad,” says Maciel. Among the products being tested are scaffolds (structural supports), biomaterial designed to be used in the production of heart valves, and meshes for repairing tendons and abdominal hernias. For the scaffolds alone there are more than a dozen distinct potential uses,” says the plastic surgeon.

The biological material used by the researchers is supplied by the UFC tilapia skin bank, built by the Biotec Solução Ambiental company and sponsored by Enel, an electric power distributor in Ceará. A pioneer in Brazil, the skin bank is currently maintained with support from Christus University Center (UNICHRISTUS), a private higher education institution in Fortaleza. The skins, obtained from fish raised in freshwater tanks, are donated by the Bomar fish company in Itarema, on the coast of Ceará State.

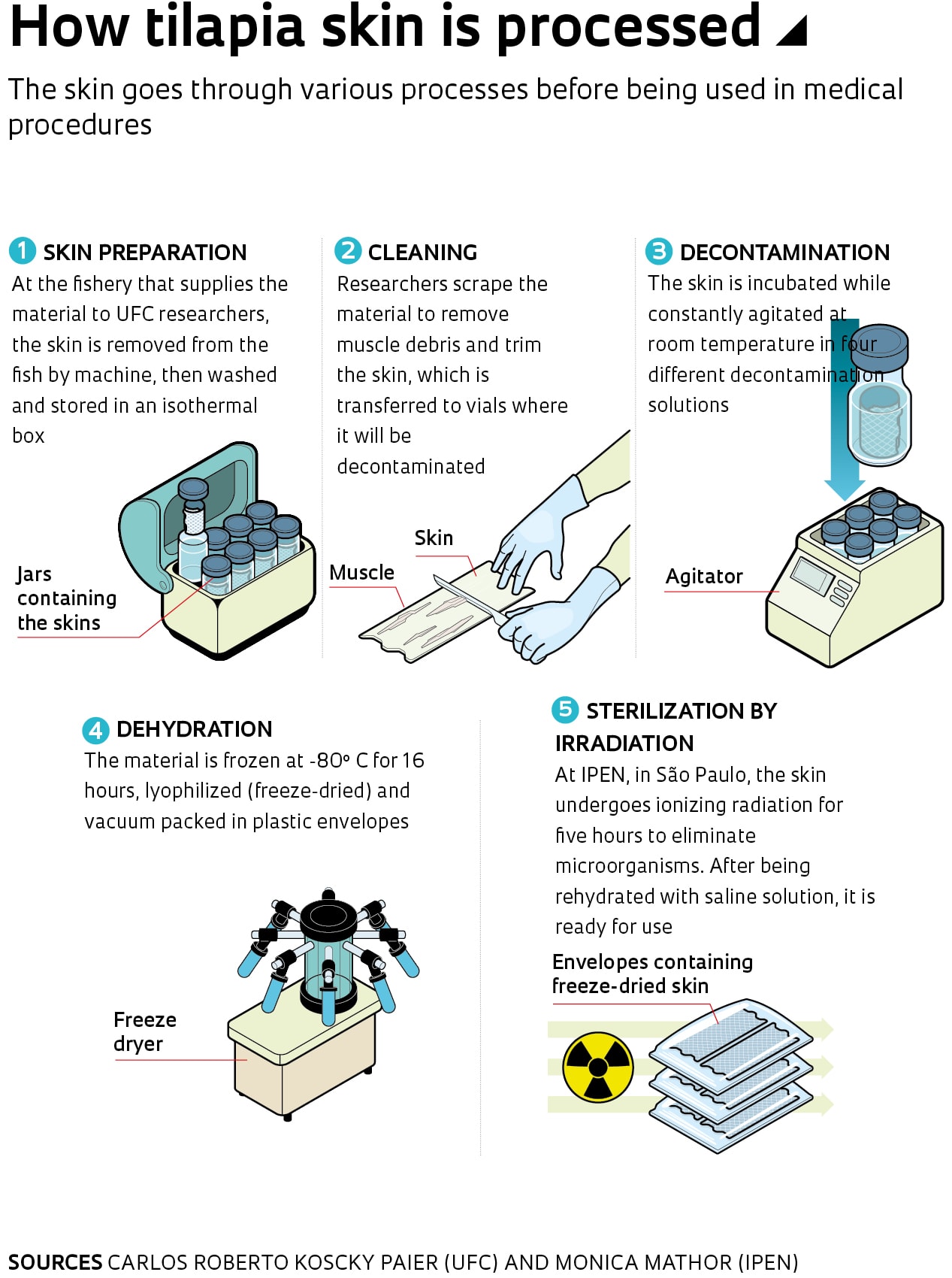

Prior to its application with patients, the material undergoes a rigorous cleaning, decontamination, and sterilization process in the UFC laboratories. At the Nuclear and Energy Research Institute (IPEN), in São Paulo, the skins are radiation sterilized in a multipurpose industrial irradiator, built by IPEN with support from FAPESP. Cleaning and sterilization removes any trace of odor from the material, though it leaves the characteristic skin design of the fish. Prior to being made available for clinical use, the skins undergo microbiological, histological, and cellular toxicity quality testing.

Faster healing

According to Odorico Moraes, among the 300 patients treated for burns to date, 30 of them children, there were no cases of infection. The Brazilian Ministry of Health is studying the inclusion of tilapia skin for the treatment of burns in the Unified Health System (SUS). In general, burn therapy uses silver sulfadiazine, an antimicrobial and healing ointment, with dressings that require daily changes. The dressings made with tilapia skin can be left on longer before replacement, saving the patient discomfort, and saving the hospital material and labor. Doctors and researchers report reduced costs, and decreased healing time and pain with the biological dressing.

The technique’s potential analgesic effect interested a group of doctoral students studying periodontics at the Bauru School of Dentistry of the University of São Paulo (FOB-USP). They are developing a pilot study for the use of tilapia biological dressings in periodontal surgical procedures, which involve the protective and supporting tissues of the teeth, such as the gums and bone. “We are very excited and the expectations are high regarding the possibility of relieving patient pain,” says Gustavo Manfredi, a doctoral student at FOB.

Viktor Braga / UFC

A researcher at the tilapia skin bank cleans and cuts fish skin material

Viktor Braga / UFC One unusual application occurred abroad. After learning about the Brazilian research, veterinarian Jamie Peyton of the University of California at Davis, in the United States, used tilapia skin to treat two bears and a mountain lion injured in California forest fires. The university reports that the bears began to walk shortly after the biological dressings were applied on their injured paws, suggesting an immediate effect in improving pain. One of the bears ended up eating the new skin, but the speedy recovery surprised the American vets.

Another experiment involving tilapia skin is expected to happen when samples are launched into space on a rocket in June. The idea came from the Louis Cruls Astronomy Club in Campos dos Goytacazes in northern Rio de Janeiro State. They are participants in the Cubes in Space program, which is partnered with NASA, the US space agency. “We’re going to look at whether the molecular structure and proteins of tilapia skin, especially type 1 collagen, will change after being in the stratosphere under low pressure and intense radiation,” says IAQ physician Edmar Maciel.

As regards the surgery performed in April on the transgender patient in Campinas, who was doing well as of mid-May, researchers expect to verify whether or not the tilapia skin will indeed transform into vaginal epithelium. “It’s not yet known if the transformation of this tissue will happen the same way as it does in women with MRKH syndrome,” says UNICAMP gynecologist Luiz Gustavo Oliveira Brito, who participated in the operation.

“The surgery isn’t new, but the material is different,” he emphasizes. In other places, he says, an amniotic (placental) membrane or synthetic material made of latex is used. He believes, however, that if there is a company that’s interested, tilapia skin could be a good alternative. “It all depends on the viability of the product.” Brito, Bezerra, and their team are working on a scientific paper reporting the case, which will be submitted for publication in the second half of this year.

Project

Construction and implementation of a Co-60 multipurpose industrial irradiator (nº 97/07136-0); Grant Mechanism Multiuser Equipment Program; Principal Investigator Leonardo Gondim de Andrade e Silva (IPEN); Investment R$1,868,012.76.

Scientific articles

MORAES, M. O. et al. Study of tensiometric properties, microbiological and collagen content in nile tilapia skin submitted to different sterilization methods. Cell and Tissue Banking. Vol. 19, ed. 3, pp. 373–82. Sept. 2018.

BEZERRA L. R. P. S. et.al. Tilapia skin fish: A new biological graft in gynecology. Revista de Medicina da UFC. Vol. 58, no. 2. 2018.

Republish