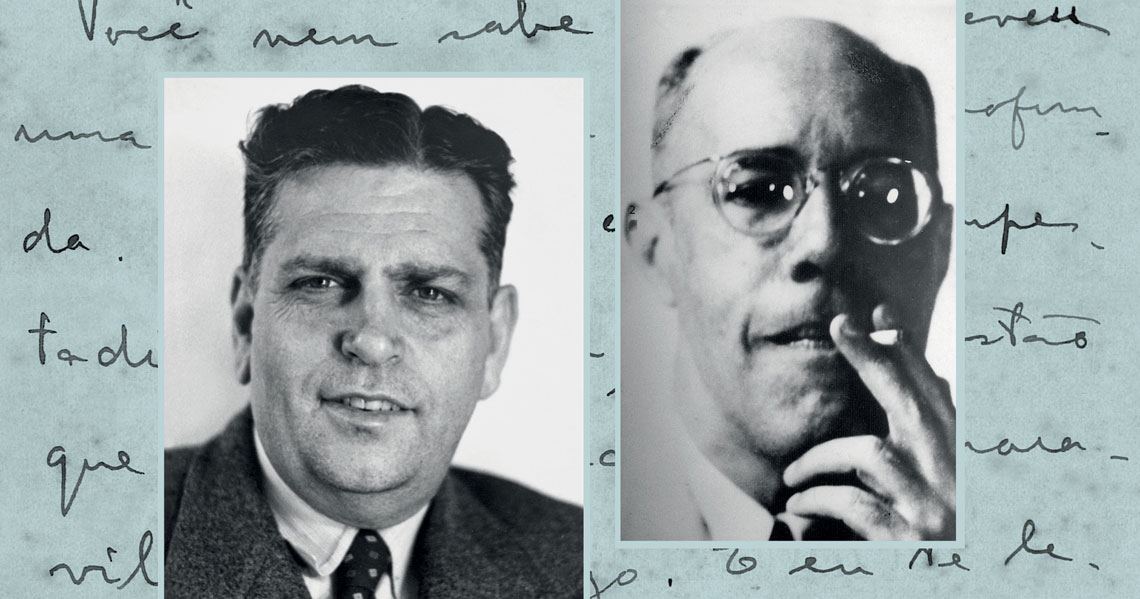

During a trip to London in February 1925, modernist author Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954) visited the British Museum and sent a postcard to Rua Lopes Chaves in São Paulo, the address of his friend Mário de Andrade (1893–1945). The souvenir reproduced the image of a wooden Amerindian rattle in the form of a bear’s head, from the institution’s collection. On the back of the card, the anthropophagist did not miss the opportunity to mock his countryman, comparing his fellow writer to the animals with the huge mouths and eyes: “I saw you today in Camden Town,” he wrote.

It was in this jocular tone, almost always playful and at the same time affectionate, that Oswald wrote to the author of Macunaíma (Macunaíma: The Hero with No Character) between 1919 and 1928, in missives now gathered in the book Correspondência Mário de Andrade & Oswald de Andrade (Correspondence […]) (Edusp/IEB-USP, 2023). In the twenty letters, one note, and six postcards, Oswald primarily tells of his efforts as propagandist of Brazilian modernism in Europe during a period of vibrant cultural activity. In Paris, he commissioned translations into French of his novel Os condenados (The condemned) (1922) and held a conference at the Sorbonne (“I am bribed by emotion”). In the same city, he met French-Swiss writer Blaise Cendrars (1887–1961) and alluded to encounters with innumerable personalities such as poet Jean Cocteau (1889–1963), “a skinny young boy with expressive crows’ feet,” and painter Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), the “Dostoevsky born in Malaga.”

The dialogue, however, is incomplete, because the replies sent by Mário to Oswald are not included in the edition. Possibly, the author of Manifesto antropófago (“The Anthropophagic Manifesto”) did not keep the correspondence that he received, unlike Mário, who over the course of his life collected more than 7,000 letters from writers, artists, musicians, and intellectuals with whom he corresponded to 1945 — the year of his passing — now under the guardianship of the University of São Paulo’s Brazilian Studies Institute (IEB-USP). The book in question is the eighth volume from the collection Correspondência (Mário de Andrade correspondence) whose forthcoming releases are set to collate exchanges between the São Paulo native writer with politician Carlos Lacerda (1914–1977), anthropologist Arthur Ramos (1903–1949), and composer Luciano Gallet (1893–1931).

In an effort to fill the gaps and reconstruct the dialogue between Mário and Oswald, the organizer of the volume, Dr. Gênese Andrade, an expert in Oswaldian works and not blood-related to the writers, added copious footnotes to supplement the content of the letters. She consulted a variety of sources to this end, including correspondence between Mário and others, such as painter Tarsila do Amaral (1886–1973), who was married to Oswald between 1926 and 1929. “Oswald’s writing style is very synthetic, cryptic, and peppered with wordplay. The footnotes aim to contextualize what he writes in the correspondence, and shines a different light on the history of modernism,” explains Andrade, literature professor at the Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP) in São Paulo.

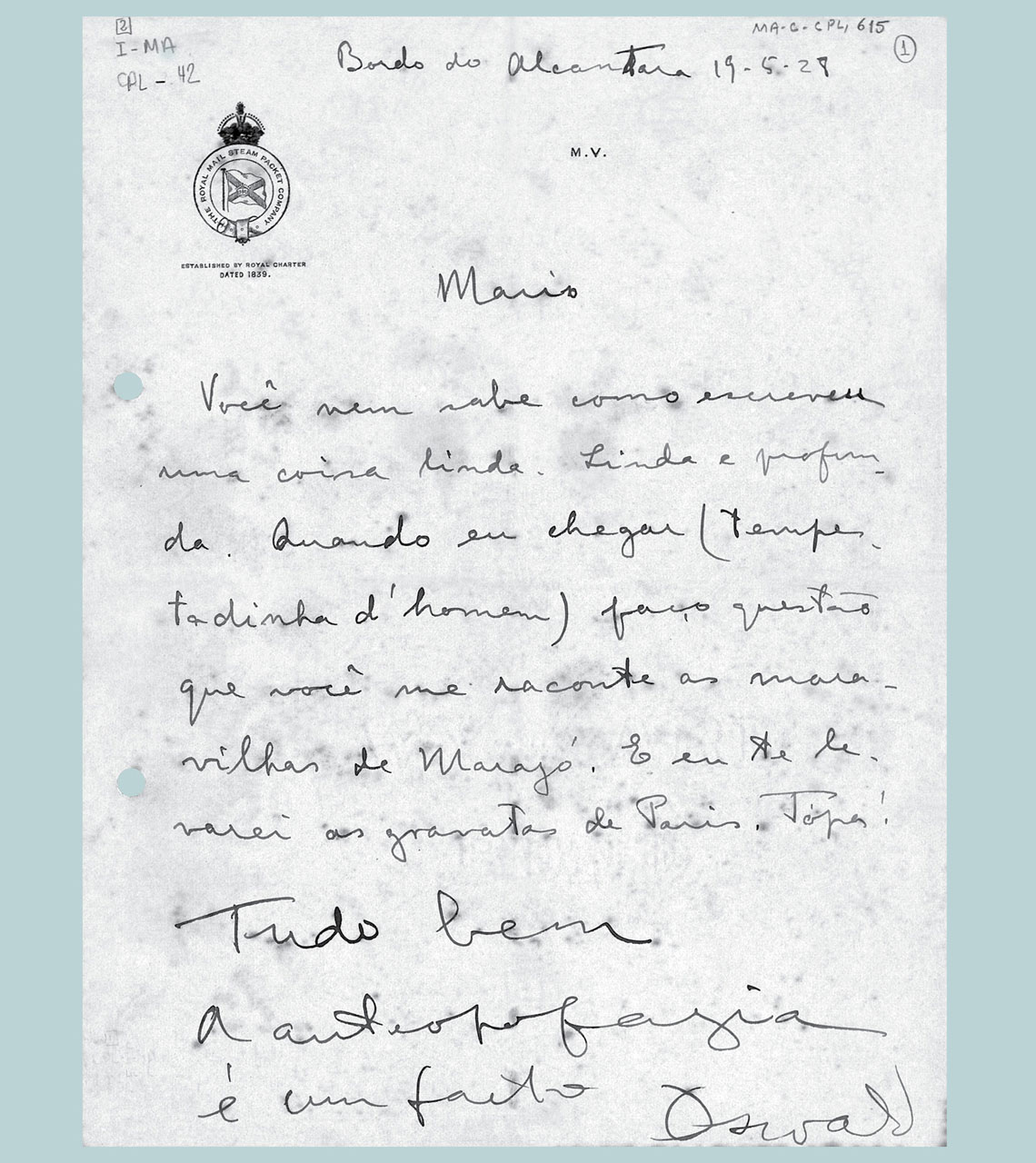

Reproduction from book Correspondência Mário de Andrade & Oswald de Andrade / Mário de Andrade Archive, IEB-USPCorrespondence sent by Oswald in May 1928, while en route to Paris: “Cannibalism is a fact”Reproduction from book Correspondência Mário de Andrade & Oswald de Andrade / Mário de Andrade Archive, IEB-USP

By way of example, the edition deciphers a letter sent from Paris in 1925, jointly signed by Oswald and writers Yan de Almeida Prado (1898–1987) and Sérgio Milliet (1898–1966). Playful in style, the manuscript mentions the characters dubbed “Desgraça Mosca,” “Santo Heitor Fura-Bolos,” and “São Villa-Buarque da Haya,” references to writer Graça Aranha (1868–1931), classical composer Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959), and historian Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1902–1982), respectively. “Mário knew the historical importance of his correspondence, which provided an insight into the ‘underground life’ of the modernist movement,” comments Marcos Antonio de Moraes, professor at IEB-USP and editorial coordinator of the collection, alongside independent researcher Tatiana Longo Figueiredo and Telê Ancona Lopez, also an IEB-USP professor. “The letter was the means by which intellectuals informally discussed aesthetic, social, and political matters, using curse words and getting creative with the language. For Mário de Andrade, these were ‘pyjama letters,’ as he registered in the Chronicle ‘Amadeu Amaral’ in 1939.”

Originally penned on a variety of writing surfaces, such as ruled, colored, or silk paper with letterheads from hotels, restaurants, and shipping lines, the letters leave clues about the places Oswald passed through, and are reproduced in facsimile form in the book. Some include sketches and caricatures. “The correspondence is not the text alone. The dimensions, the type of paper used, and the whole material aspects of the letter suggest meanings, perceived by scholars,” Moraes goes on.

According to critic Antonio Arnoni Prado (1943–2022), Oswald and Mário, “two opposite and complimentary souls of the modernist spirit,” had a tumultuous friendship marked by conflicts of personality and mutual intellectual admiration. The relationship began in 1917, when the then young journalist Oswald was impressed with a speech given by Mário at the São Paulo Drama and Music Conservatory. In 1921, influenced by the verses of Pauliceia desvairada (Frantic São Paulo), a book that would be released the following year, Oswald publicly praised Mário in the article “O meu poeta futurista” (My futuristic poet), published in the Jornal do Commercio (Trade Journal). Shortly thereafter, in 1922, both were active participants in Modern Art Week at the São Paulo Municipal Theater. Their friendship, however, soon began to falter as their intellectual differences emerged.

“In 1924, Mário diverged on certain points of Manifesto da poesia pau–brasil (Manifesto of Brazilwood Poetry), published by Oswald in the newspaper Correio da Manhã, due to its analytical view of Brazil, and for this reason he travels to the country’s Northeast to research popular culture and analyze elements which, for him, were a constituent part of Brazilian culture. Oswald, on the other hand, was intuitive. He had a more immediate outlook on the national reality,” observes Eduardo Jardim, a retired philosophy professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RIO) and author of the biography Eu sou trezentos: Mário de Andrade: Vida e obra (I am three hundred: Mário de Andrade: Life and work) (Edições de Janeiro, 2015). According to Jardim, Oswald’s letters to Mário primarily illustrate the interest among modernists in making contacts with the European avant-garde. “Oswald wanted to get Brazil into the ‘concerto of cultured nations,’ which at that time he considered to be France,” the researcher goes on.

In 1925, Mário dedicated the book A escrava que não é Isaura (The slave who is not Isaura) to Oswald, who sent thanks from Paris with a letter parodying his friend’s style: “It was a commotion for me, your offring [sic] your book to me,” wrote the traveler. In this same period, the two created a poem between them, “Homenagem aos homens que agem” (Homage to men who act) (1927), signed by “Marioswald,” which would be part of an original-release book, Oswaldário dos Andrades (Oswaldary of the Andrades). The permanent break between the two came in 1929, for reasons not clear to date. In the hypothesis of researchers such as Aracy Amaral, Mário is said to have been the target of a series of attacks and provocations in Revista de Antropofagia (Anthropophagy journal) then in its second phase. One of these, the article “Miss Macunaíma,” published in June of that year, alluded to his homosexuality, a taboo subject at the time.

“Oswald was a joker who at times used very malicious wordplay against his friend. The letters document his boyish, playful, sometimes cruel spirit, with no measurement of the consequences of his attitudes. Mário, in correspondence with poet Manuel Bandeira [1886–1968], commented how much this troubled him,” says Gênese Andrade. “After their break, their mutual intellectual admiration survived; their shared respect continued in the world of ideas, reading and appreciating each other’s works, but Oswald’s attempts at reconciliation were never accepted by Mário,” concludes the researcher.

Republish