What are deforested areas in the Legal Amazon used for? In 2008, Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) launched the TerraClass project, with the objective of identifying how land is being used where natural vegetation had been removed. Based on the location and level of deforestation detected by the PRODES system, teams from both organizations used remote sensing to determine whether the rainforest had been cleared for crops, pasture, or much more rarely, urban areas and other forms of occupation.

They have created overviews of the Legal Amazon for five different years: 2004, 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014. Due to a lack of funding and personnel, TerraClass stopped carrying out the survey in recent years. But now it is back. A new form of the project, funded by the Ministry of Defense’s Management and Operations Center for the Amazon Protection System (CENSIPAM), recently shared 2020 land use data online. Due to methodological changes, it has not yet been possible to compare the information from 2020 with previous years.

– Multiple systems use satellites to monitor deforestation in the Amazon

– Guide to Amazon snakes launched at the Butantan Institute

– The roots of Amazonian biodiversity

– Communication and diet different in urban primates

– Ima Vieira: Restore the forest with justice

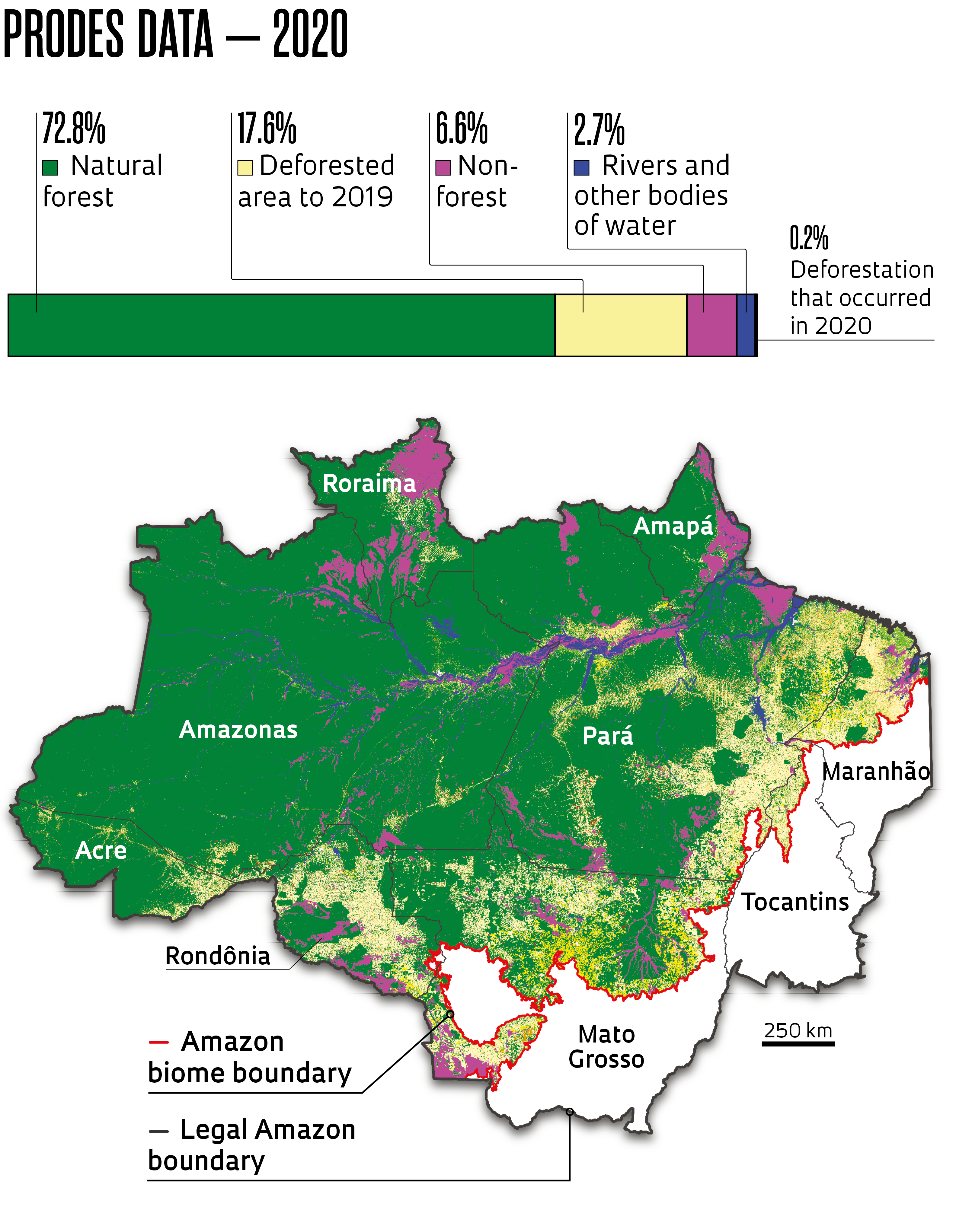

In the past, TerraClass processed and analyzed data relating to the Legal Amazon, an area of around 5 million square kilometers (km2) that encompasses the entire Amazon rainforest and parts of the Cerrado (a wooded savanna biome) and Pantanal. Now, the project is generating information specifically related to the Amazon biome, which is around 800,000 km2 smaller than the Legal Amazon.

One of the reasons for the change was the creation of a Cerrado-specific TerraClass in 2018—the Cerrado is one of the largest agricultural regions in the country. The new approach thus eliminates overlaps and redundancies by using two different initiatives to focus on the two largest Brazilian ecosystems, which cover more than 70% of the national territory.

“We are just finishing the process of migrating the old TerraClass to this new format,” says agronomist Júlio César Dalla Mora Esquerdo of EMBRAPA Digital Agriculture in Campinas, one of the project’s coordinators. “We plan to make data for 2022 available soon.” The team also intends to look back into the past and map land use and cover for the years 2016 and 2018, at which time TerraClass Amazônia was no longer in operation.

There is also a TerraClass Brasil version, created with support from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) to map land use across all biomes in the country. “Knowing our national territorial dynamics will enhance the synergy between economic, social, and environmental development policies,” says Alexandre Coutinho, a researcher at EMBRAPA Digital Agriculture.