In October 1970, art critic Mário Pedrosa (1900–1981) disembarked in Santiago, Chile, seeking political asylum. In Brazil, he had been accused of defaming the military dictatorship (1964–1985) by denouncing the practice of torturing political prisoners. At the time, he was already 70 years of age, which did not stop him from continuing to work: “A new exile is not comfortable in old age. But here I am and I begin again a life that has never stopped beginning again. And so it is that I begin again, creating a museum of modern and experimental art that life has named the Museum of Solidarity,” he wrote to Mexican painter Mathias Goeritz (1915–1990).

The invitation to lead the creation of the new institution came from Salvador Allende (1908–1973) himself, the recently elected president of Chile at the time. Thanks to his vast network of contacts in the art world, Pedrosa mobilized names such as Catalan artist Joan Miró (1893–1983), Brazilian artist Lygia Clark (1920–1988), and US artist Frank Stella, who all sent works for the new museum, inaugurated in the capital of Chile in May 1972. “It was a museum with a collection made entirely of donations, with the objective of supporting Allende’s socialist government. In one year, it received over 600 works,” says sociologist Glaucia Villas Bôas, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and author of Mário Pedrosa: Crítico de arte e da modernidade (Mário Pedrosa: A critic of art and modernity; Editora UFRJ). Released last year, the book joins other publications that have come out recently about the life and work of the intellectual.

Interrupted by the coup of General Augusto Pinochet (1915–2006), the Brazilian’s exile in Chile illustrates the strong entanglement between art and politics that marked his biography. Born in Timbaúba, Pernambuco State, Pedrosa came into contact with Marxist ideas at the National School of Law, in Rio de Janeiro, which would become a unit of UFRJ. He joined the Communist Party in 1925. Two years later, he left Brazil for the Soviet Union to study in the International Lenin School in Moscow, but became ill and changed his plans: he stayed in Berlin, where he attended university courses in sociology and philosophy, as well as taking part in political activities against the Nazis. It was in the German capital where he adhered to the ideas of the International Left Opposition, a group led by Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), who was opposed to Stalinism.

Pedrosa had already published a range of political articles in the Brazilian press when, in 1933, he made his debut as an art critic with a text about German printmaker Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945). “It is the first Brazilian sociology-based essay on modern art. He explains the artistic phenomenon with scientific rigor and begins from the dynamic of social structures to understand what an artistic manifestation is within a specific society,” points out philosopher Marcelo Mari, of the Department of Visual Arts of the University of Brasília (UnB), who organized the book Mário Pedrosa: Revolução sensível (Mário Pedrosa: Sensitive revolution; Edições SESC, 2023), with historians Francisco Alambert and Everaldo de Oliveira Andrade, of the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP).

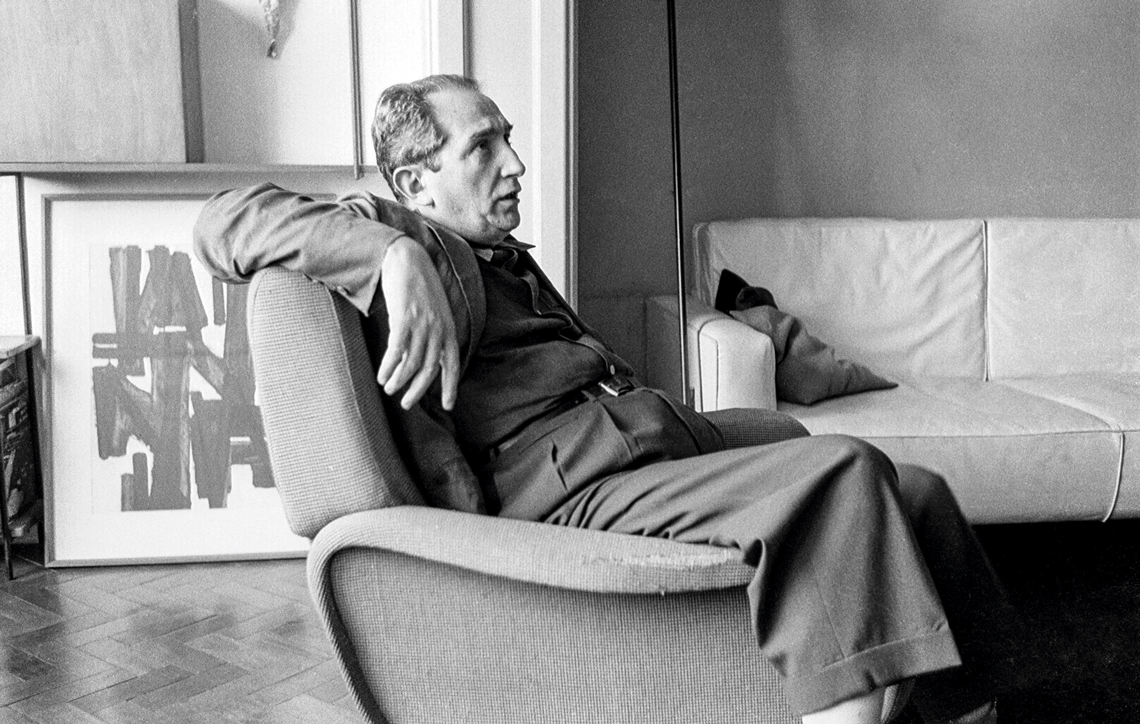

Athayde de Barros / São Paulo Biennial Foundation / Historical Archive Opening of the VI Biennial of São Paulo, in 1961, which had Pedrosa as artistic directorAthayde de Barros / São Paulo Biennial Foundation / Historical Archive

In the following years, the critic wrote essays about the painter Candido Portinari (1903–1962), defending engaging and libertarian art, but not pamphleteering. “Pedrosa wanted to revive Brazilian art in the second half of the 1940s, which, in his view, was stagnant. For him, the realism of Portinari and Di Cavalcanti [1897–1976] would serve as an ideological instrument of the Estado Novo [1937–1945] and as a basis for the construction of an official Brazilianness of the Vargas government,” explains Mari.

In the USA, where he went into exile after suffering persecution for his political militancy during the dictatorship of the Estado Novo, Pedrosa deepened his formulations about artistic modernity. In New York, he was impacted by the sculptures of US artist Alexander Calder (1898–1976), with whom he became friends. “It is democratic art because it can be made from anything, fits anywhere, at the service of any condition, noble, rare, or common; and serves to revitalize the joy and the sense of harmony, now blunted, of man,” wrote the critic in the article “Calder, escultor de cataventos” (Calder, sculptor of wind vanes), published in 1944. From there, Pedrosa moves away from figurative art and towards nonrepresentative expressions, such as abstractionism.

“The first texts by Mário Pedrosa express a vision of art with a social commitment. Little by little, he enriches this vision and starts to incorporate elements of Gestalt, the German form of psychology,” observes journalist Luiz Antônio Araujo, professor at the School of Communication, Arts, and Design of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS), who is preparing a biography of the critic for publishing company Record, still without a release date. “Pedrosa values the work of Calder for recovering day-to-day objects and materials. Lots of people did not think that his mobiles, moving suspended structures, could be considered art. And it is in this same direction that he guides the first generation of concrete artists in Brazil, such as Ivan Serpa [1923–1973], Abraham Palatnik [1928–2020], Lygia Clark, and Hélio Oiticica [1937–1980].”

In 1945, with the end of the Second World War and the dictatorship of the Estado Novo, Pedrosa returns from exile in the USA. The following year, he creates a column dedicated exclusively to the visual arts in the Correio da Manhã newspaper and in the 1950s intensifies his activity as a critic in the public sphere. “Pedrosa didn’t want his reflection about art to be confined to artists or to the gallery- and biennial-attending public. He wanted to be heard on a wide level, and at that time the printed newspaper was a space with large circulation and respectability,” adds Araújo.

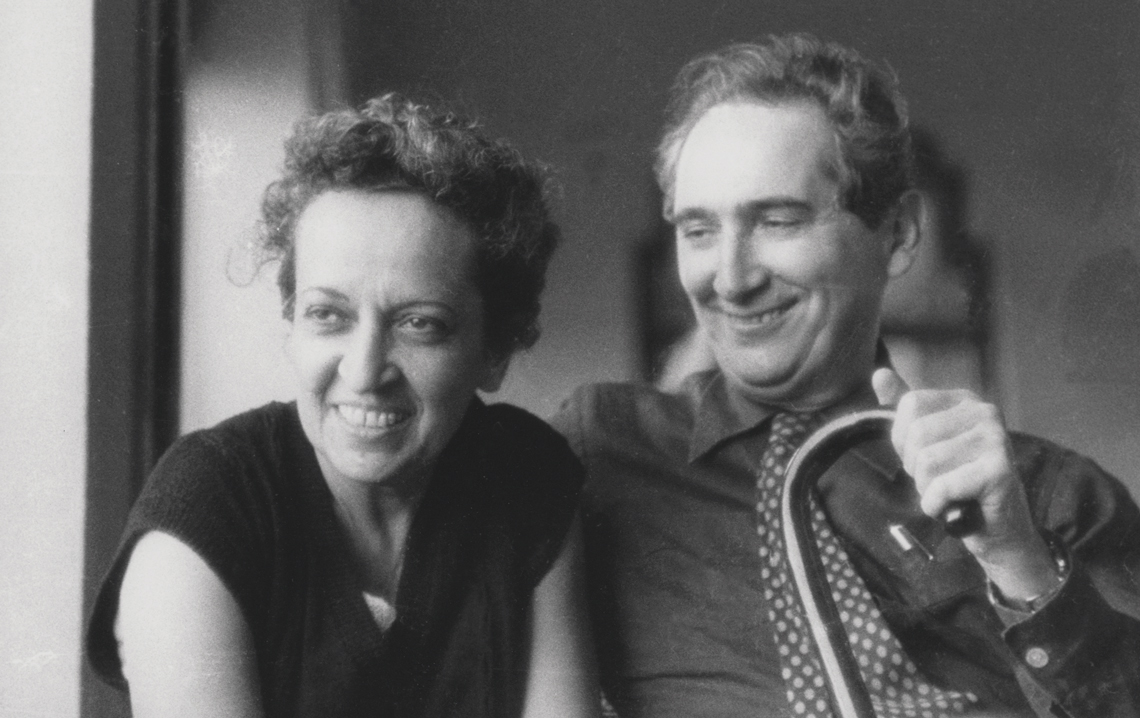

Unknown author / Center for the study of the Workers' Movement (CEMAP) – Collection from the Documentation and Memory Center of São Paulo State University (CEDEM/UNESP) With his wife Mary Houston, a civil servant and translator, in India, 1959Unknown author / Center for the study of the Workers' Movement (CEMAP) – Collection from the Documentation and Memory Center of São Paulo State University (CEDEM/UNESP)

With a regular presence in the Jornal do Brasil newspaper as well, Pedrosa is today regarded as one of the great renovators of art criticism in Brazil by specialists. Until then, it was an activity mainly done by the literati, such as Mário de Andrade (1893–1945), with whom Pedrosa corresponded. Throughout five decades working as a critic, Pedrosa constantly reworked his thinking about art, always paying attention to the international scene. For him, every and any individual was a potential artist, “regardless of their meridian, whether they are Papuan or Afro-Indigenous, Brazilian or Russian, Black or yellow, literate or illiterate, balanced or unbalanced,” as he recorded in an article published in 1947, in the Correio da Manhã.

This is how he turns his attention to the “virgin art” produced by the artists from the Engenho de Dentro studio, in the Pedro II Psychiatric Hospital, in Rio de Janeiro, to which he dedicated several articles in the Correio da Manhã. Pedrosa frequently visited the space created in 1946 by psychiatrist Nise da Silveira (1905–1999) in the company of young painters such as Serpa, Palatnik, and Almir Mavignier (1925–2018). Influenced by the artists within the institution and by the critic’s ideas, little by little they abandoned figurative painting and embraced the concrete art that would emerge from Rio de Janeiro in the 1950s.

According to Villas Bôas, of UFRJ, the technical coldness and rationality of modern society became targets for Pedrosa: “He thought that art had the mission to help the individual recover lost sensitivity in an increasingly fast-paced world.” His conception of modernity, universalist in nature, adds the researcher, differs from the vision of Mário de Andrade, focused on the construction of a national identity. Pedrosa also emphasizes dialogue with the past and cultural differences: in 1961, as artistic director of the VI Biennial of São Paulo, the critic from Pernambuco caused a splash by uniting African and Aboriginal Australian art, Japanese calligraphy, and works by modernists such as German artist Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948).

In 1977, with the start of the redemocratization process in Brazil, Pedrosa returned from exile in Paris, where he had been taken refuge after the military coup in Chile. During this period, he noticed that the cycle of modern art had been exhausted and, together with artist Lygia Pape (1927–2004), conceived an exhibition about Indigenous art for the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro (MAM Rio). Titled Alegria de viver, alegria de criar (Joy of living, joy of creating), the exhibition aimed “to show Brazilians that the cultural phenomenon of artistic creativity is not a phenomenon of progress, it is experience, living, homogeneity, and defense of the virtues of the communities still alive,” as the critic wrote in Jornal do Brasil. According to Marcelo Mari, from UnB, at the end of his life Pedrosa perceived that contemporary art had become an object of consumption accommodated to the status quo and was incapable of changing reality. “So, he then turns his attention to other experiences, such as Indigenous art. He was decolonial, before the term existed,” he defines.

Unknown Author / Nise da Silveira Archive / Friends Society of the Museum of the UnconsciousThe critic and psychiatrist Nise da Silveira in the National Museum of Fine Arts, in Rio de Janeiro, 1980Unknown Author / Nise da Silveira Archive / Friends Society of the Museum of the Unconscious

However, a fire in 1978 destroyed part of MAM Rio, preventing the event from being held. In its place, the critic proposed the creation of the Museum of Origins, which would unite five institutions: MAM Rio itself, as well as the Museum of Indigenous Peoples, the Museum of the Unconscious, the Black History Museum, and the Museum of Popular Arts. The initiative did not go ahead, but calls attention today for having highlighted, in a pioneering way, the artistic production of historically marginalized groups.

Confusing itself with the political and cultural history of the twentieth century, the eventful life of Mário Pedrosa came to an end in November 1981. A victim of cancer, he died in Rio de Janeiro aged 81. One year before, in São Paulo, he had signed the founding book of the Worker’s Party, becoming its first member.

Since the publication between 1995 and 2000 of the four volumes of his Textos escolhidos (Chosen texts; EDUSP), organized by philosopher Otília Arantes, of USP, there has been a growing interest from researchers in the life and work of the intellectual. In 2015, the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York gathered part of his writing in English in the series Primary documents. Last year, the publishing company Companhia das Letras launched the collection of essays Obra crítica, vol. 1: Das tendências sociais da arte à natureza afetiva da forma (1927 a 1951) (Critical work, vol. 1: From the social tendencies of art to the affective nature of form [1927 to 1951]), arranged by musician Quito Pedrosa, the critic’s grandson. “Pedrosa thought not only about culture, but about Brazil. He was not just a reproducer of European ideas: he came up with unprecedented concepts to understand Brazil. That is why he deserves to be read and studied,” concludes Andrade of FFLCH-USP.

Republish