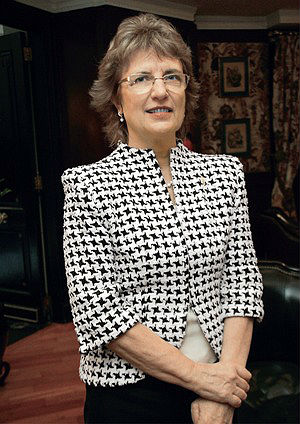

ANDRÉS PÉREZ MORENO / EL PAÍSThe routine of Argentine astrophysicist Marta Rovira, a researcher at the Institute of Astronomy and Space Physics (Iafe) of the University of Buenos Aires, was radically transformed in April 2008, when she became president of the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (Conicet is the acronym in Spanish), Argentina’s foremost agency for the promotion of science and technology. She is the first woman to head this entity, created in 1958 by Bernardo Houssay, the 1947 Medicine Nobel Prize laureate. As the head of Conicet, Marta Rovira has led a strategy that has been reviving the country’s scientific accomplishments, which had been adversely affected by severe budget restraints in the 1990s and by the serious economic crisis that devastated the country’s economic policy, based on the peso to the dollar parity. This economic crisis ultimately led to the resignation, in December 2001, of Argentina’s then president, Fernando de la Rúa. The budget allocated for Conicet shot up from less than US$ 100 million in 2003 to US$ 335 million last year. This enabled Argentina’s 142 research institutes – most of them linked to universities, as is the case of Iafe – and 12 regional science and technology centers to increase the number of researchers from 3,804 in 2003 to 6,350 last year. In line with this pace, the number of scholarship grantees went up from 2,378 to 8,122 in the period. The strategy also includes the repatriation of Argentine researchers who had left the country because of the crisis in the early 2000s – Argentina had already been affected by a brain drain in the 1970s, caused by the military dictatorship, and in the 1960s, when skilled scientists were attracted by rising opportunities in the United States and Europe. A program called Raíces has managed to repatriate about 100 Argentine researchers a year, placing them in universities, companies and, above all, in job openings at Conicet itself. Marta Rovira, who has a PhD. in physics from the University of Buenos Aires, has written more than 120 scientific articles. She was the head of Iafe from 1995 to 2008. Her main interest is solar physics, especially the study of active solar phenomena and the Earth-Sun relationship. She was president of the Argentine Astronomy Association for three terms and is currently vice president of the International Astronomical Union. This interview to Pesquisa FAPESP was held at her office in Buenos Aires:

ANDRÉS PÉREZ MORENO / EL PAÍSThe routine of Argentine astrophysicist Marta Rovira, a researcher at the Institute of Astronomy and Space Physics (Iafe) of the University of Buenos Aires, was radically transformed in April 2008, when she became president of the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (Conicet is the acronym in Spanish), Argentina’s foremost agency for the promotion of science and technology. She is the first woman to head this entity, created in 1958 by Bernardo Houssay, the 1947 Medicine Nobel Prize laureate. As the head of Conicet, Marta Rovira has led a strategy that has been reviving the country’s scientific accomplishments, which had been adversely affected by severe budget restraints in the 1990s and by the serious economic crisis that devastated the country’s economic policy, based on the peso to the dollar parity. This economic crisis ultimately led to the resignation, in December 2001, of Argentina’s then president, Fernando de la Rúa. The budget allocated for Conicet shot up from less than US$ 100 million in 2003 to US$ 335 million last year. This enabled Argentina’s 142 research institutes – most of them linked to universities, as is the case of Iafe – and 12 regional science and technology centers to increase the number of researchers from 3,804 in 2003 to 6,350 last year. In line with this pace, the number of scholarship grantees went up from 2,378 to 8,122 in the period. The strategy also includes the repatriation of Argentine researchers who had left the country because of the crisis in the early 2000s – Argentina had already been affected by a brain drain in the 1970s, caused by the military dictatorship, and in the 1960s, when skilled scientists were attracted by rising opportunities in the United States and Europe. A program called Raíces has managed to repatriate about 100 Argentine researchers a year, placing them in universities, companies and, above all, in job openings at Conicet itself. Marta Rovira, who has a PhD. in physics from the University of Buenos Aires, has written more than 120 scientific articles. She was the head of Iafe from 1995 to 2008. Her main interest is solar physics, especially the study of active solar phenomena and the Earth-Sun relationship. She was president of the Argentine Astronomy Association for three terms and is currently vice president of the International Astronomical Union. This interview to Pesquisa FAPESP was held at her office in Buenos Aires:

Conicet’s budget went up by more than 400% in dollar terms from 2003 to 2010. How was it possible to increase investments in science and technology during times when the country was undergoing budget constraints and had to deal with growing demands from other areas?

It was clearly a government policy. The government decided to increase the budget for science and technology. This allowed more researchers, grantees and employees to enter the system. The number of people – including all categories – rose from 9 thousand in 2003 to more than 17 thousand in 2010. The government decided to increase the Conicet budget, which led to more job openings and enabled salaries to be paid.

Is it possible to measure the impact of the growth in the number of grants and job openings? Did any areas stand out?

It’s very difficult to say who stood out. Some themes are forgotten or generate a bias that depends on the education of the person who is doing the analysis. At Conicet, providing grants and entry into the research profession have always taken place according to priority. The advisory committees establish an order based on the background history and the production of each researcher and the researchers join the system according to this order. Last year, we decided to change this rule for the first time. We established that 80% of the researchers would join on the basis of merit, because excellence is the overall objective. The other 20% were to fulfill regional needs and strategic knowledge areas. The objective is to guide research projects towards themes that we consider the most important. But above all we want to ensure that the needs of the country’s different regions are met.

Could you give an example?

Conicet’s structure is comprised of 12 science and technology centers located in various regions. The needs of the population of Mendoza [Argentina’s fourth biggest city and a major wine and food production center], where one of our centers is located, are completely different from the needs of the population of Ushuaia, the capital of the province of Tierra del Fuego and home of the Austral Center for Scientific Research. So we are taking these needs into account. The research studies conducted in this region must somehow link up with the interests of the government and the society of that region. This had not been taken into account previously. The criteria were the candidates’ background. Our population is mostly concentrated in the center of our country. We have to ensure that research groups exist and flourish both in the north and in the south. Eighty percent of our researchers are found in Buenos Aires, Santa Fé, Rosário, Córdoba and Mendoza.

Are researchers willing to work in distant regions?

Are researchers willing to work in distant regions?

We are creating incentives to attract researchers to those regions. It is very likely that there are not enough senior researchers to lead research teams. A lot depends on the themes. Life in those regions can be very different. It is one thing to live in Buenos Aires; but it is entirely different to live in Ushuaia, where it is very cold. Researchers that go there can earn as much as 60% more in some places than they would earn in the capital of our country. But the salaries are not high enough to make people desperate to live there. Some people like to go to those regions. We´re thinking about providing a housing allowance because housing can be very expensive in some of those places. We are also considering granting other benefits to attract researchers.

Approximately 40% of the scientific studies at Conicet are conducted in partnership with other countries. In Brazil, international collaboration has remained at 30% for several years. How do you evaluate the current level of cooperation between Brazil and Argentina and the possibilities that might arise?

We have many agreements with Brazilian universities and agencies, but there is also a lot of research collaboration between Brazilians and Argentines that is not linked to any of these agreements. Science is universal and interdisciplinary. It’s very important to have partnerships with other countries, not because other countries are better than or different from our country. The point is that joint work is very interesting. In my professional field, for example – I study the Sun. Satellite images are very important in this kind of research work. Various research groups start to work as soon as images are placed at everybody’s disposal. More and more, data related to various areas has become public so that the entire community can use it.

Your professional field is involved in a collaboration with Brazil. The Solar Submillimeter Wave Telescope (SST) was installed in the late 1990s in the El Leoncito (Casleo) Astronomy Complex, which is linked to Conicet. This was a joint initiative with the Center of Radio Astronomy and Astrophysics of Mackenzie (Craam), with funding from FAPESP.

Professor Pierre Kauffman [a Brazilian astrophysicist and researcher of Craam] brought the solar radio telescope to El Leoncito, in the Argentine Andes, and it is working very well. The conditions to install the telescope were very good. Other telescopes had already been installed at Casleo, there was already a structure in place…

Is there any area in which Argentina has a special interest in collaborating with Brazil? The cooperation agreement signed last year by Conicet and FAPESP covers all fields of knowledge.

Collaboration with Brazil involves physics more than any other field. Thirty two percent of the articles published by Brazilian researchers from 2000 to 2009 were connected with physical sciences; 15%, with biological sciences;13%, with chemical sciences; and 10% with basic medicine. But I don’t think there were any guidelines regarding this. I think it is the result of the natural collaboration dynamics in these areas. Data from 2007 show that Brazil ranked third as the country with which researchers from Conicet published the greatest number of collaborative articles. The United States ranked first and Spain ranked second in this respect.

At a lecture during which you referred to the challenges faced by Conicet, you mentioned the need to investing in internationalization, without disregarding the need to increasingly meet regional demands. How can you reconcile the two?

We must continue doing basic science research. Because basic science is the starting point for the applied sciences, for technological development. In general, research into basic science is published in international journals. This is a requirement that attests to the quality of the research. When the journal is good, the papers are usually good as well. Now we would like research groups working in a specific region to dedicate more time to the given region’s problems. Of course, not all the research teams will be doing this. But it is necessary to have a certain percentage of these researchers dedicating their time to the given region to solve the problems and improve the lives of the people who live there. These are not mutually exclusive objectives. Many technological developments are turned into something that can actually be transferred to society after a couple of years.

Argentina’s ranking in education – in both elementary and secondary education – are higher than those in Brazil. On the other hand, Brazil has created a post-graduate system that is unique in Latin America. What can each country learn from the other?

Brazil invests more in science than Argentina does. It has many more grant holders and PhDs. Since 2003, Argentina has increased investments in science. In 2007, the Argentine Government created the Ministry of Science. I don’t have information on elementary and secondary education in Brazil, but I do know that Brazil has been growing in terms of science and technology in the last few years.

Hugo Lovisolo, an Argentine sociologist who lives in Brazil, wrote about the difference between the two countries’ university and science and technology systems. He pointed out that Brazil has invested in universities that focus on research and postgraduate studies, while Argentina has invested in institutions that focus on educating a huge number of undergraduate students and on meeting the needs of society. Do you agree with this evaluation?

I am not familiar with this issue as regards Brazil. But in Argentina, some years ago, researchers were accepted according to their backgrounds, but the themes that they researched were not taken into account. Now, however, the focus on themes that enable transfer of technology is stronger. We want to foster research groups, within the hierarchy of our system, which carry more weight and act as the middlemen between research study results that are transferable and the companies that can apply these results in commercial terms. Most researchers do not like to deal with the business community and prefer to dedicate their time to their research work. Many things are being done with transferable results, but researchers in general are not prepared to talk to companies and to sell the results of their research work. The government has implemented a policy to encourage this.

Is the emphasis on technological transfer a way of legitimizing, for society, the growing investment in science?

Is the emphasis on technological transfer a way of legitimizing, for society, the growing investment in science?

There is no condition that states that in order to invest in science we have to transfer the results to society. But we are living in a period in which we believe that if it is possible to transfer something then we have to do so. The government doesn’t tell us that it will only provide funds if we transfer something to society. The government would like this to happen but it doesn’t force us to do it.

And are the results appearing?

Some developments entail the participation of researchers and companies. I usually refer to the Yogurito case as an example of this. Yogurito is a dairy product; more specifically, it is a yogurt that is marketed by a company that resorted to research work to ensure that this yogurt is appropriate for children and that it would protect them from respiratory and intestinal diseases. This is a good example of a partnership between an institution and a company. An agreement signed by Conicet and the province of Tucumán ensured the supply of yogurt to 56 thousand students. There are other examples, such as the development of genetically modified poultry capable of producing proteins that are of interest to the pharmaceutical industry; of virus-resistant potatoes, and of various genetically modified plants. We want to foster this, we want to encourage stronger ties between research institutions and companies. One of Conicet’s objectives is to narrow the gap between science and society and to show society that research outcomes help people lead better lives.

Does society acknowledge this effort?

Society does not acknowledge this effort to any great extent because society is not really familiar with the kind of work the researchers do at Conicet. This is why a press and communication department was created last year to provide us with more exposure, so that people could become acquainted with the work that our researchers are involved in. The researchers themselves are the ones who really know what kind of work is being done at Conicet.

During her presidential campaign, President Cristina Kirchner’s propaganda included the results of government programs to repatriate Argentine scientists who had emigrated abroad. Is Argentina still undergoing a brain drain?

At this moment, what is drawing attention is the fortunate fact that researchers are returning. Many of them are coming back. Every year, 100 to 110 researchers come back to Conicet. We have a repatriation program called Raices. We try to incorporate any researcher who wants to come back to Argentina to work at Conicet, at universities or at other institutions.

Are attractive job openings available to those who come back? Are they able to work?

Conicet is one of the destinations. A high percentage of researchers who return from abroad are easily accepted at the institutions linked to Conicet, because they generally have better qualifications than those who never left. I believe they are coming back because now they have better working conditions. In the last few years, the funds allocated to the purchase of equipment have increased, which has allowed us to purchase quite competitive, state-of-the-art equipment. The laboratories are now better equipped and can provide researchers with better working conditions, similar to what they enjoyed abroad. Salaries are reasonable – they are much higher now than a few years ago. The number of grant holders has also increased significantly. In 2003, all researchers who wanted to enter this career were accepted. Last year, approximately 130 did not enter this field, even though they had been approved at all levels by their peers on the advisory committees. We also have a program that provides subsidies for companies that employ researchers. If a given company requests researchers with a specific background, then Conicet asks the researchers whether they want their CV to be forwarded to the company , which then interviews them. This program has recently been implemented. For example, two researchers have already joined a company and we have other examples as well. We would like researchers to be employed by the ministries, by government. Researchers from Conicet are working at the Atomic Energy Commission, at ministries, in different places. We would like companies to employ more PhDs, even if they do not dedicate themselves specifically to the area they graduated in. A doctoral program offers the kind of educational skills that allow researchers to be involved in fields other than those that they got their degrees in.

Some people say that more scientists should live abroad permanently, because they can act as international facilitators for researchers working in their native countries, and thus help collaborations materialize. Is there any positive aspect to the brain drain?

It is a fact that a high percentage of the Argentine researchers who live abroad collaborate with their peers in Argentina. A kind of relationship is somehow established, which can be beneficial. They are still Argentines, even though they live abroad.

In early October, a ranking of Latin American universities prepared by British company QS ranked Brazil as the leader, with 65 of the 200 highest ranked universities on the list. This is nearly double the number of universities in Mexico (35) and much higher than Argentina and Chile (25 each). Does this result worry you?

Honestly, I cannot voice an opinion on rankings. But we have strong ties with the universities, because our grantees are linked to them. We pay stipends for the grantees to study, but the universities educate them. A grantee is defined as someone who has concluded his or her undergraduate studies and who has a total of five years – divided into two stages – to conclude a doctoral program. Conicet provides the stipends and the diploma is granted by the public or private university where the grantee is enrolled. Most of the institutes under Conicet, many of which are in the central region, are in university premises. Nearly 90% of our researchers are linked to universities. A researcher working at Conicet is obliged to have a postgraduate degree to qualify for one of the four categories (assistant, adjunct, independent, and principal) and to qualify as a senior researcher.

The National Agency for the Promotion of Science and Technology (ANPCyT) was created in 1996 to provide more flexibility to the funding allocated for research in Argentina. It was widely believed that the structure of Conicet had become too big to look after the institutes and scholarship grantees and think about broad strategies. At one of your recent lectures, you stated that one of Conicet’s challenges is to improve its processes. Are there any issues in this respect?

No. We currently have 22 advisory committees, linked to four major areas (biological sciences, exact and natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities, and agriculture and engineering]. These committees meet once a month to evaluate enrollments, resources, and job relocation, as well as scholarship candidates. These are significant numbers. Another 22 committees were created for the same disciplines. Everything is done via the internet – evaluations, enrollments, everything. Some documents have a hard copy for legal reasons, but we use the digital format for assessments.

What is the relationship between Conicet and ANPCyT like?

The agency depends on the Ministry of Sciences, just like Conicet does. Conicet has scholarship grantees, researchers, support staff, whereas the agency has no researchers that depend on it. The agency provides stipends that many researchers from Conicet apply for. Researchers can get substantial funding for their projects.

They work in a complementary way…

The researchers forward requests not only for research and equipment purchase fund but also for repatriation. Prior to the agency’s creation, the funds for research projects had been provided by Conicet. Approximately three years ago, Conicet started to fund research projects again. The agency, on the other hand, has funds allocated for research, such as the funds granted by Conicet, as well as for specific themes linked to the so-called sector funds, which focus on more specific issues (upgrading of laboratories, information technology, and energy, among others). Anybody who works in these fields qualifies for funding. In my opinion, these two models complement each other. The agency does not have institutes or research personnel, but it provides funding.

Two years ago I interviewed an Argentine scientist, bioscientist Alberto Kornblihtt, from the University of Buenos Aires. He was interested in learning how FAPESP works. I explained that, since the 1960s, the Foundation has been allotted a percentage of tax revenue to invest in research. He pointed out that this kind of investment regularity was not available in Argentina. What is the adverse effect of this?

It’s very difficult to move forward with a research project if you don’t know how much money will be available. You have to count on at least a minimum level, especially in the case of applied developments, which require several types of equipment. Researchers have to know whether money will be available to purchase equipment or to update it. In my opinion, applied science has not been fully developed in Argentina in the past because there was no assurance that money would be available the following year to continue the research work.

Yet Argentina was able to maintain a consistent scientific basis…

True, but equipment doesn’t last forever. It breaks down, becomes obsolete, other far more advanced instruments become available. Equipment must be constantly upgraded to enable researchers to work competitively.