The 40th anniversary of a key moment in Brazil’s democratic transition—the inauguration of the first civilian president after 21 years of military dictatorship—holds special meaning for the country’s scientific community. On that day, March 15, 1985, the Ministry of Science and Technology was established within the federal government—finally centralizing what had long been a fragmented and loosely coordinated array of federal science initiatives and programs. Renamed the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) in 2011, the agency has played a key role in shaping and institutionalizing science policy, even as it has weathered successive budget cuts and restructuring—over the years, it has been downgraded from cabinet level or merged with other ministries on several occasions.

Leadership turnover has been constant: of the 25 ministers who have headed the ministry, 15 served for a year or less. Still, a strong bureaucratic backbone has taken shape over time. The ministry now employs 5,982 staff to keep the MCTI running and support its wide-ranging mission. Its mandate—spanning from basic science to innovation in industry—is implemented through two main grant-making bodies: the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP). The MCTI also runs 18 research institutes that either conduct science directly or provide infrastructure for researchers—among them the Brazilian Center for Physics Research, the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE), and the National Laboratory of Scientific Computing (LNCC). Also under its umbrella are two autonomous federal agencies—the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB) and the National Nuclear Energy Commission (CNEN)—as well as advisory and regulatory bodies such as the National Biosafety Technical Commission (CTNBIO) and the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA). The ministry also oversees Ceitec, a public corporation specializing in semiconductor R&D and manufacturing.

MCTI funding has supported the construction of major research facilities, such as the Sirius synchrotron light source, and has been earmarked for future facilities like the Orion high-containment biosafety lab and the Brazilian Multipurpose Reactor—a center for producing radioisotopes and tracers used in agriculture and other applications. The Ministry’s 2025 budget, approved by Brazil’s Congress on March 19, stands at R$13.7 billion—an increase over 2024, though still R$3 billion short of what had been proposed in the federal budget draft. That puts it on par with funding levels seen between 2010 and 2015, a high point for public investment in science—and well above the reduced budgets of 2016–2021.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPThe Sirius synchrotron light source in Campinas was built using funds from the MCTI budgetLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

For Luciana Santos, an engineer and the current Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation, establishing a dedicated ministry was a turning point that gave science the importance it deserved. “That’s when we began building a national science policy, strengthening universities and research institutes, launching strategic programs, and making sure innovation was aligned with Brazil’s needs,” she says. The idea to elevate science and technology to the cabinet level had been in circulation for decades. It gained traction after the creation of federal agencies like CNPq and CAPES in 1951, during the second presidency of Getúlio Vargas. Influential figures like physicist José Leite Lopes (1918–2006) and hematologist Walter Oswaldo Cruz (1910–1967) argued for a dedicated ministry in opinion pieces published in the late 1950s.

The Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC) backed the proposal as well, according to physicist José Goldemberg, who served as SBPC president from 1979 to 1981. Goldemberg notes that, after World War II, the consensus globally was that science policy required a dedicated agency, preferably at the cabinet level, to be effectively implemented. “There had to be an organization devoted to training scientists, supporting research, and coordinating related activities,” he explains. “And there was also the symbolic value of science having a seat at the government’s top table.” Goldemberg himself would later serve as Special Secretary for Science and Technology in 1990, during a period when the agency was briefly downgraded.

Personal archiveSecretary José Goldemberg with President Collor during the decommissioning of a nuclear test site in Serra do Cachimbo, 1990Personal archive

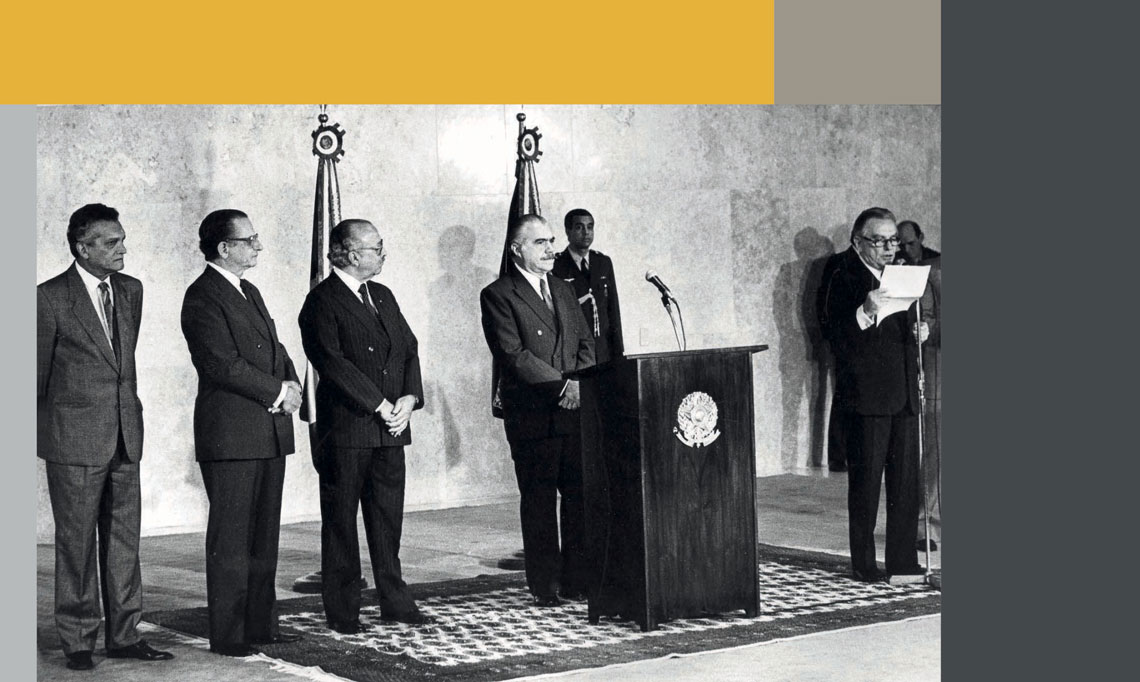

The decision to establish the ministry came from President-elect Tancredo Neves (1910–1985) in 1985. Though he fell gravely ill before his inauguration and died weeks later, his pick was honored by his vice president and successor, José Sarney. Neves tapped Renato Archer (1922–1996), a nationalist and former Foreign Minister (1963), to lead the new science and technology ministry. “Archer had once been a Navy officer and had close ties with Admiral Álvaro Alberto da Mota e Silva [1889–1976], who founded CNPq. He was also a mining entrepreneur and a former congressman who had lost his seat. In many ways, he embodied all the different players who had pushed for a science ministry—he just wasn’t a physicist,” says science historian Antonio Augusto Passos Videira, a researcher at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and author of the book 25 anos de MCT: Raízes históricas da criação de um ministério (25 years of the MCT: The making of a ministry; CGEE, 2008).

The ministry’s early days gave little indication it would last. Early reactions included skepticism—most notably from José Reis (1907–2002), a pioneering science communicator, who feared that institutionalizing science policy might create a wall between researchers and the halls of power. During his tenure of two years and seven months, Archer worked to forge ties with the research community. He invited former SBPC president and respected geneticist Crodowaldo Pavan [1919–2009] to head CNPq. Funding from the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT)—the main federal science funding mechanism—had dried up during the last years of the military regime but was replenished with fresh funding to re-equip laboratories.

In 1989, the ministry was merged with the Ministry of Industry and Commerce, then downgraded to a secretariat under President Collor, reporting directly to the presidency. José Goldemberg, who served as Science and Technology Secretary during this period, says the loss of ministry status was not a major setback. “What really matters is how much access you have to the president. And in my case, there was strong engagement,” he says. “Two major initiatives defined our agenda: preparing for the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 and winding down Brazil’s secret nuclear weapons program,” he says.

The ministry was reestablished under President Itamar Franco [1930–2011] and entered a relatively stable phase. Chemist José Israel Vargas headed the ministry for over five years, continuing into the early tenure of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso. In a 2008 interview with Pesquisa FAPESP, Vargas recalled that proceeds from the privatization of Brazil’s National Steel Company helped launch major initiatives—including the creation of the Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies (CPTEC) under the INPE, the relocation of the National Laboratory for Scientific Computing (LNCC) from Rio to Petrópolis, and final construction of the National Synchrotron Light Laboratory in Campinas.

MCT archiveMCT Executive Secretary Pacheco (left), minister Ronaldo Sardenberg, and FINEP President Mauro Marcondes, in 2002MCT archive

During Cardoso’s second term, Minister Ronaldo Sardenberg—a career diplomat—and executive secretary Carlos Américo Pacheco, an engineer, laid the groundwork for a new funding model that brought more financial stability to the ministry and the FNDCT. The result was the creation of 16 Sectoral Funds for Science and Technology—14 dedicated to specific economic sectors like energy, health, and biotech, and two cross-sector funds designed to support university-industry collaboration and improve the infrastructure of scientific institutions. Each fund drew on earmarked revenues. For example, the energy fund collects 0.3% to 0.4% of gross revenue from electric utilities.

These funds were intended to supplement federal allocations to the FNDCT, with most of the funding going to research aligned with the priorities of each economic sector. In practice, however, this sector-specific focus eroded over time, and much of the funding ended up supporting the ministry’s general operations and projects. Making matters worse, portions of the funds were often withheld—or “sequestered”—to service Brazil’s national debt. In 2021, Brazil’s Congress passed a law prohibiting the federal government from freezing these funds. “It was during Sardenberg’s tenure that the MCTI took on its current form, with research institutes becoming directly affiliated with the ministry rather than with CNPq, and with the inclusion of AEB and CNEN,” says Carlos Américo Pacheco, now executive director of the FAPESP Executive Board.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPFifth National Conference on Science, Technology, and Innovation, held in Brasília in 2024: the conference developed recommendations for a 10-year roadmapLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Other ministries—like Agriculture, Education, Health, and Defense—run their own science-related programs and institutions. But the MCTI is tasked with coordinating research efforts and formulating national-level science and technology policy. Just last year, with support from subject-matter experts, the MCTI drafted Brazil’s National Artificial Intelligence Roadmap. Still, the ministry’s ability to influence broader government policy has long faced constraints, says engineer Clélio Campolina Diniz, a professor and former dean at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, who served as MCTI minister from March 2014 to January 2015. “Science and technology policy needs to be planned over the medium to long term,” he says. “It should support broader national development goals and integrate with other strategic policy areas—such as industry, agriculture, trade, education, and public health.”

As an example of how this coordination has been wanting, Campolina cites the tax breaks given to multinational companies in the Manaus Free Trade Zone. “These companies should have been required, in exchange, to base their R&D operations in Brazil—but that was never demanded.” He also points to the country’s current dependence on imported seeds for genetically modified soy. “Brazil’s science sector is more than capable of advancing a national policy to domestically produce agricultural technologies,” he says. While in office, Campolina launched a program, called Knowledge Platforms, to foster academic-industry collaboration in tackling industrial technology challenges. The initiative, however, was not carried forward by subsequent administrations.

Antonio Videira, from UERJ, believes the ministry has struggled to foster the kind of critical thinking that could help steer science policy in new directions. “The ministry has a very broad mandate and an array of practical issues to address,” he says. “It oversees research institutes with diverse missions, juggles persistent funding constraints, and has to respond to an ever-expanding list of demands—from government-driven inclusion policies to emerging topics like artificial intelligence. It can sometimes seem overwhelmed or unable to step back and reflect independently on where science policy should be heading.” While Videira sees the past 40 years as broadly positive, he regrets that public and political assessments of the ministry often hinge on budgetary factors alone. “The narrative tends to be: if there’s money, the ministry is doing well; if there isn’t, it’s failing,” he says. “That’s far too narrow a way to measure success. It overlooks a wide array of initiatives and policy work the ministry undertakes. What we need is a more serious conversation about how science can best serve society and development.”

Marcelo Camargo / Agência BrasilChildren at an event during National Science, Technology, and Innovation Week, organized by the MCTI since 2004Marcelo Camargo / Agência Brasil

Physicist Sérgio Machado Rezende, who served as minister from 2005 to 2010, recalls what he considers a high point for the ministry. In early 2004, his predecessor—federal congressman Eduardo Campos (1965–2014)—took the helm and immediately called on his team to help craft a comprehensive national science and technology policy. At the time, Rezende was president of FINEP. “Campos had the clarity to see that the ministry needed a coherent strategy. We were all holed up in Brasília for three days,” he recalls.

When Rezende took over, he decided to build on that effort. In 2007, he convened leaders from across the scientific community to help design a Science and Technology Roadmap covering 2007–2010. The plan, informally dubbed the “Science and Technology PAC” (Growth Acceleration Program), was soon implemented. “It’s crucial that the ministry draw inputs from scientists and society at large in developing its strategy,” Rezende says. Last year, he led the 5th National Conference on Science, Technology, and Innovation at the ministry’s request. The conference produced a series of recommendations for a national science strategy, which will soon be published in a roadmap known as the “Purple Book” (Livro Violeta).

The story above was published with the title “At the cabinet level” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Republish