If you’re walking a trail through some tropical South American forest, your attention may be drawn by a sudden blue flash that quickly disappears. It could be a Morpho butterfly. If you try to capture the insect you’ll probably have difficulty due to the flashing, which deceives the eye, and this happens because the blue marking is exposed to daylight on the upper surface of the wings, while the underside is brown. If you fail in your capture attempt, it gets worse: the butterfly moves more frenetically, changing direction on each wing beat. The difficulty faced by human observers also goes for birds, the natural predators of these insects. The function of this mesmerizing coloring has always been a mystery—until now. A group from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) demonstrated its protective role in an article published in the scientific journal Ethology in December.

“The difficulty in following these butterflies with the human eye has been tested by other groups during simulations, such as computer games in which human volunteers played the part of predators,” explains biologist André Freitas, one of the advisors on the study. “But no one had tested it in the field with real predators.” The researcher, a butterfly specialist, spent years talking about this with his colleague and former advisor Paulo Oliveira, whose research focus is insect behavior, primarily that of ants, and had proposed the idea. There was a need for someone motivated to do the work, and in 2020 along came biologist Aline Vieira e Silva, who had just been co-advised by the two professors on her master’s.

Vincent Debat / MNHNIn other species of this genus, the dorsal wing surfaces are colored, though not always blue, and the ventral sides are brown, with false-eye markingsVincent Debat / MNHN

The study was conducted at the Serra do Japi Biological Reserve, about 50 kilometers (km) southeast of Campinas, São Paulo State. The Morpho helenor is prolific there, mostly during February, March, September, and October—periods in which the student concentrated her fieldwork from 2021. The main predators are tyrant flycatchers of the species Megarynchus pitangua, Pitangus sulphuratus, and Myiodynastes maculatus, and thrushes of the rufous-bellied (Turdus rufiventris) and pale-breasted (T. leucomelas) varieties.

The study required capturing the butterflies with nets and trail traps with bait of mashed banana mixed with sugarcane juice, fermented for at least 48 hours. Seem strange? Well, these butterflies feed mostly on fruits that fall from the trees and gradually rot on the ground. As well as persistence on her many walks, normally assisted by colleague Gabriel Banov, also doing master’s research into this species, Vieira had to develop artistic talents: the experiments involved the very delicate task of painting the butterfly’s wings.

One challenge was to find the right paint. After all, the Morpho’s blue does not come from pigment, but from tiny scales within a nanoscopic structure that spreads the light in a specific manner, always reflecting the same color. The sheen, though, varies depending on light occurrence and the angle of observation, and this could not be reproduced. However, a blue metallic paint got close to the color, which the researchers checked using a spectrometer measuring the emitted light wavelength. Thus, the back of the wing assumed a similar blue hue, but not iridescent. Vieira was careful not to use oil-based paint—which would compromise the butterfly’s flight—and allowed the insect to dry before being released.

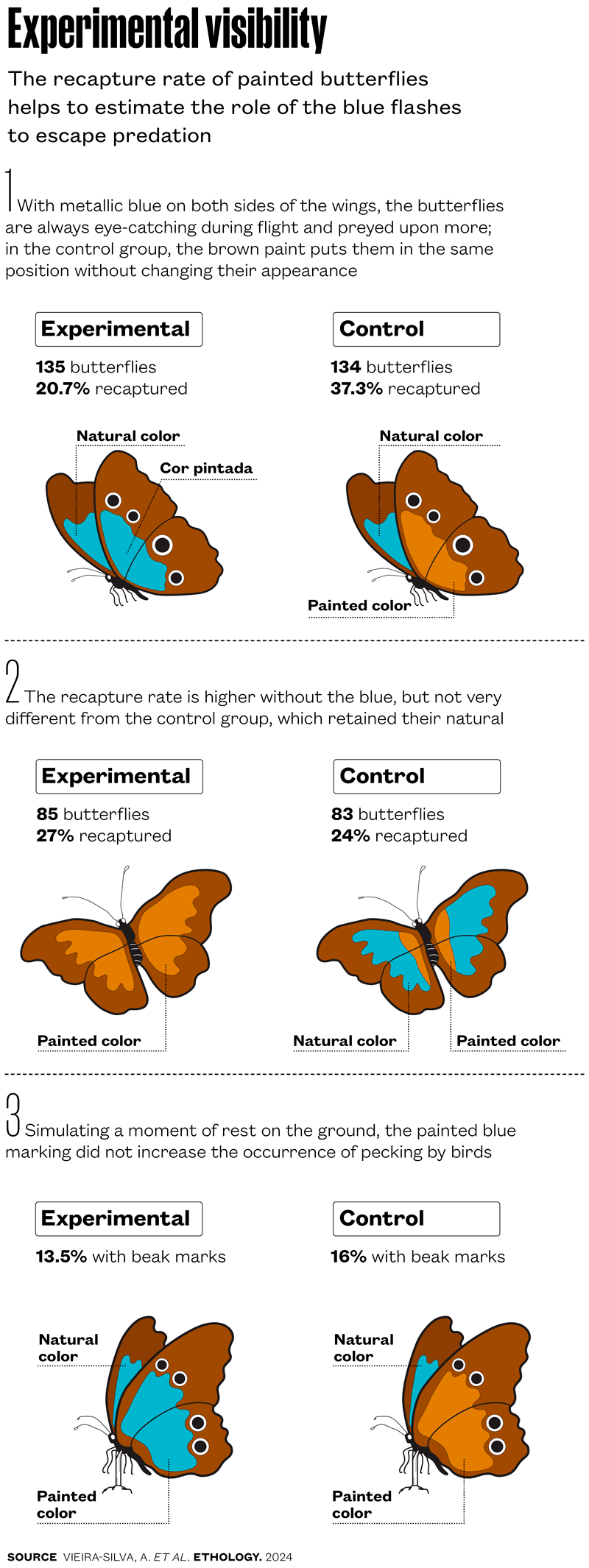

The aim of the first experiment was to eliminate the flash effect by painting a blue strip on the lower part of the wings, which made the butterfly shimmer regardless of the wing position. “The blue with the same reflectance removes the flash effect, because the color is always on show during flight,” she explains. The butterfly group with blue on both sides of the wing (135 in total) was compared to another 134 of the same species, with the same wing area (naturally brown) painted brown (see infographic). This latter was the control group, with no visible alterations, but the specimens were painted to eliminate the possibility of the observed effect being due to the application of paint and not the color. Vieira also wrote a number in one corner of the wing with a black marker to identify any recaptured butterflies. Having both sides blue caused a considerable impact on the capacity for recapture: over 30 consecutive days, during morning and afternoon outings come rain or shine, she reencountered 20.7% of the butterflies painted blue, and 37.3% of those that had received a brown stripe.

“Birds capture prey during flight,” says the researcher. “It was important that the blue did not disappear for our successful interpretation of predatory activity.”

Blue on both sides of the wings would appear to be bad business. The emergence and maintenance of the eye-catching color are an evolutionary mystery, but according to Freitas, it comes from way back. The ancestral species of M. helenor should be blue, a useful feature for discrimination between males and females. “They are not expected to lose their coloring for the benefit of being cryptic [confused with the environment], in detriment to communication within the species,” the biologist states.

Vieira tested the survival advantage. She painted the blue stripe of 85 butterflies brown, and a brown stripe on a further 83 others as control, without covering the iridescent blue. She recaptured 27% of the experimental group, and 24% of the control group—not a significant difference.

And what happens when they land? Under these circumstances they are generally well camouflaged among the dry leaves, because only the brown of the closed wings is on show. And if that were not the case? Vieira pinned dead butterflies to small spread boards, with the outer face of the wings painted either blue or brown, and pinned them into the ground. She saw no great difference between the small triangles left by birds’ beaks: 13.5% of the blue, and 16.5% of the brown butterflies were pecked. This outcome backs the perception that flycatchers and thrushes hunt in flight rather than landing on the forest floor.

“The predatory pressure from visually oriented birds is very high in the tropical region, and has favored the evolution of defense strategies,” says Paulo Oliveira, who co-advised on the study. Freitas and Vieira now say they are curious to know whether the trend they observed occurs in other places. “Could the difference be even more marked in the Amazon region, which has more predators?” she asks. The ideal scenario would be other research groups being inspired to check it out.

If German biologist Wolfgang Goymann, editor of the journal Ethology, is right, there is a good chance that will happen. “Some of the studies published in our journal have been reproduced in textbooks or classic citations,” he wrote in his editorial. Goymann is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence in Germany. “I believe that this article has the potential to become a classic citation of the flash-coloration hypothesis of predator distraction,” he concludes.

Gabriel Banov / UnicampDelicate wing painting (left): on the underside with brown paint for control (above), and blue to eliminate the flash effect in flightGabriel Banov / Unicamp

“Our experiment canceled out the butterfly’s strategy—we made it stop disappearing during flight,” jokes Oliveira, celebrating the new understanding of something that has captivated researchers for more than 150 years. “The factors that most helped [British naturalist Charles] Darwin [1809–1882] to corroborate his ideas were insect defense strategies,” he adds. In his book The Naturalist on the River Amazonas, first published in 1864 (a Brazilian version released by publishing house Itatiaia went out of print in 1979), British naturalist Henry Walter Bates (1825–1892) described M. rhetenor as having a dazzling sheen on the back of its wings. “When it comes sailing along, it occasionally flaps its wings, and then the blue surface flashes in the sunlight, so that it is visible a quarter of a mile off.”

Oliveira also asserts Vieira’s work for its experimental focus. “Until the mid-twentieth century, those who studied ethology (animal behavior) were seen as amateurs; it was not considered a serious science.”

French evolutionist Vincent Debat, a researcher at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, has for the last decade dedicated his studies to the flight of Morpho butterflies, among other models. “The Morphos of Amazonia are very different from those in the Atlantic Forest,” said Debat, who did not participate in Vieira’s study, during a videocall with Pesquisa FAPESP.

The coloration varies greatly between species of the genus: it could be white, orange, or brown; the flight styles are also different. As Bates observed in the nineteenth century, they float between the tree canopies, gliding, hardly fluttering their wings. In those circumstances, they appear not to use the flash facility. Those of the forest understory, such as M. helenor, fly one meter (m) off the ground, with abrupt wing movements. Debat says that they are so difficult to catch, some birds don’t even try. They see them going past and seem to think it’s not worth it. It is a considerable challenge, however, to study these strategies in more depth in a real-life situation. “It’s more common to do observations in the laboratory using flight cages,” he says. In nature you need to install cameras and hope that the butterflies pass through, using pieces of shiny blue paper as bait to attract the Morpho.

“Aline and her colleagues spent a lot of time in the field; it’s a really challenging study and the article is very important,” says Debat, who takes the view that there are still mysteries surrounding the emergence of coloration so visible and apparently costly in terms of natural selection. “We thought we knew why they had this color, but we still don’t have the answer.” Sexual selection is the go-to theory, but the fact that males and females are similar in many of the species causes a certain degree of confusion. In the animal world, it is common for males to be flashy to attract female attention.

A recent study by Debat’s group, led by doctoral student Joséphine Ledamoisel, compares two Amazon species on the matter of coloration: M. helenor and M. achilles. Individuals from both species have very similar iridescence in the areas where they coexist, suggesting mimicry as a defense against predators—it is advantageous to be confused with a difficult-to-capture neighbor. The visual similarity may hamper reproductive encounters between the two species, but the pairs are guided more by chemical signatures, according to an as-yet unpublished article, lodged with the bioRxiv repository in February.

“There must have been coevolution between the coloration and type of flight, whether gliding or escaping,” proposes Debat. Just as the flashing blue confuses predators, the interspersed role of sexual selection and survival from predators in the evolution of these butterflies will probably confound researchers for some time.

The story above was published with the title “It’s blue… or is it?” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Projects

1. Evolutionary mechanisms that determine diversity and distribution in a tropical biodiversity hotspot (nº 22/06529-2); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator André Victor Lucci Freitas (UNICAMP); Investment R$419,679.34.

2. Ecology of neotropical ants: Tritrophic interactions, associated microbiota, and population genetics (nº 22/06529-2); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Program Biota; Principal Investigator Paulo Sergio Moreira Carvalho de Oliveira (UNICAMP); Investment R$114,462.90.

3. The importance of the color pattern of Morpho helenor (Nymphalidae: Morphinae) in reducing predation by birds: An experimental approach (nº 20/06756-3); Grant Mechanism Master’s Fellowship; Supervisor Paulo Sergio Moreira Carvalho de Oliveira (UNICAMP); Beneficiary Aline Vieira e Silva; Investment R$34,124.31.

Scientific articles

VIEIRA-SILVA, A. et al. The relevance of flash coloration against avian predation in a Morpho butterfly: A field experiment in a tropical rainforest. Ethology. Vol. 130, no. 12, e13517. Dec. 2024.

LEDAMOISEL, J. et al. Sending mixed signals: Convergent iridescence and divergent chemical signals in sympatric sister-species of Amazonian butterflies. bioRxiv. Feb. 9, 2025.

Republish