Researchers from Brazil, Argentina, and France are working together to define and shortly announce the main lines of the first research projects to be funded through the Program for the South Atlantic and Antarctica (PROASA), presented publicly at the beginning of April. Planned since 2018, the first FAPESP research program focused on the sea and the icy continent intends to expand scientific knowledge about the region, strengthen national and international research networks, establish integrated and ongoing monitoring of this part of the Atlantic, and promote sustainable development.

“It’s not possible to pursue sustainability without considering these two environments, the importance they have, how vulnerable they are, and the gaps in knowledge about them,” explains the coordinator of the program, biologist Alexander Turra, of the Institute of Oceanography of the University of São Paulo (IO-USP). “There is also an international consensus that it is necessary to expand the volume of investment in ocean sciences and the program seeks to collaborate in this effort.” PROASA follows the principles of the Ocean Decade (2021–2030), coordinated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 321).

Initially formed by FAPESP, the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), and the National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina (CONICET), PROASA intends to encourage the participation of other national and international institutions that can produce and apply the information resulting from the scientific projects.

“Without scientific research, governance of the sea would be impossible,” commented rear admiral Ricardo Jaques Ferreira, secretary of the Interministerial Commission on Marine Resources (CIRM), of the Brazilian Navy, which has supported expeditions since 1982 and coordinates the Brazilian Antarctic Program (PROANTAR). One of the purposes of PROASA is to boost funding for ongoing research in Antarctica.

“Our knowledge about the ocean is insufficient to reach sustainable solutions,” stressed diplomat Peter William Thomson, special envoy for the ocean of the United Nations (UN), who took part, via video, in the program launch. Turra adds: “We need to share information.”

“The quantity of available data about the South Atlantic is surprisingly scarce compared, for example, with the North Atlantic. One of PROASA’s aims is to help fill this gap and bring new contributions in all areas of knowledge, including physical and biological oceanography, oceanic resources, the role in determining rain pattern, as well as economic questions, international relations, and scientific diplomacy,” says Marco Antonio Zago, president of the FAPESP Board of Trustees, at the opening of the event, as reported by Agência FAPESP.

In the assessment of physical oceanographer Olga Sato, also of the IO-USP, countries from the region, although they maintain computational infrastructures with different degrees of maturity, should adopt the same procedures for storing and sharing the data from their research. “In analogy to spoken language, if everyone speaks a different language when expressing their ideas, nobody will be able to understand. We need to have standardization of how data are included in databases so that sharing is efficient,” he commented. “We don’t have to reinvent anything, but work to standardize the protocols used by the databases.”

Sato was the Brazilian representative in the November 2023 meeting in Cape Town, South Africa, for the All-Atlantic Ocean Research and Innovation Alliance (AANCHOR). Composed of 16 countries from Europe, Africa, and South America, AANCHOR is an expression of the Belém Declaration, an agreement signed at the Belém Tower, in Lisbon, in 2017, to increase joint oceanic research about the South and North Atlantic. In 2023, the All-Atlantic Alliance launched the pilot project All-Atlantic Data Enterprise 2030 (AA-DATA2030), coordinated by Sato, to connect regional information networks about the South Atlantic in an open transnational database.

“Brazil, with a coastline that covers half of the South Atlantic, has an important role in the international cooperation agreements,” says biologist Andrea Cancela da Cruz, general coordinator of Sciences for the Ocean and Antarctica, of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI). Brazil, she stressed, has participated in dialogues about ocean science in IBSA (India, Brazil, and South Africa) since 2005 and in the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) Working Group on Ocean and Polar Science and Technology since 2017, whose members met for the first time in July 2018, in Brasília.

For British and Brazilian international relations expert Maísa Edwards, “the countries have to think together about how to resolve the big global issues, such as climate change.” In an article published in May 2023 in the journal Conflict, Security & Development and in her PhD, defended in June last year, within the scope of the double degree program between King’s College London and USP, she examined the history and evolution of the South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone (ZOPACAS).

Based on documents from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Brazil and the UN, combined with interviews with ambassadors and diplomats, she concluded that Brazil has held a position of leadership since the creation of this zone of peace, established in 1986 by the General Assembly of the UN, with 22 member nations from South America and Africa (Namibia and South Africa joined later). The first meetings were in Rio de Janeiro in 1988 and in Brasília in 1994.

A decade after what Edwards calls “relative dormancy,” there has been a revitalization of the ZOPACAS: 16 of the 24 members returned to meet in April 2023, in Cape Verde, and the next meeting is forecast for 2026 in Brazil. “The ZOPACAS is important for promoting peace and strengthening the ties between member nations,” says the researcher. Established to avoid the militarization and proliferation of nuclear arms in the South Atlantic during the Cold War (1947–1991) and now seen as strategic to combating piracy and arms and drugs trafficking in the South Atlantic, the ZOPACAS will be able to support scientific activities, including the mapping and exploration of the seabed.

The increased attention to the so-called South–South agreements represents a resurgence of the foreign policy agenda from the early 2000s, after which international investments and dialogue died down, in the assessment of political scientist Janina Onuki, of the Department of Political Science at USP. “Brazil is attempting to regain at least part of the leadership it has lost in recent years in two areas in which it feels comfortable, science and environment, but the international scenario has changed in 20 years,” she adds. “There are now strong competitors, like China, also interested in the leadership and with more resources to invest.”

This portion of the Atlantic, delimited to the north by the Equator and to the south by Antarctica, covers 40.2 million square kilometers (km2), a little less than the North Atlantic (41.3 million km2). This immense mass of salt water was decisive for the history of Brazil, for being the route of the winds that propelled the Portuguese caravels in the sixteenth century, and exerts great influence over the climate of the surrounding continents. It was an important area for the transport of gold, silver, wood, sugar, and slaves until the first half of the nineteenth century and is still part of the maritime trade routes today.

Cooperation with the Navy

From a scientific perspective, the South Atlantic is the least known of the oceans. “It was the last to form after the separation of South America and Africa and is surrounded by developing countries, the majority without many resources to invest in science,” says biologist Frederico Brandini, of the IO-USP. “For many years, like us, Argentine researchers relied on Navy ships to see where and when they could do fieldwork.” On the first trips of the Brazilian Antarctic Program, he remembers, it was necessary to insist with the commanders of the Navy ship Barão de Teffé to take the same route as on previous trips, since they had to compare the results of the collections of marine organisms.

On one of the trips to Antarctica, as the ship passed through the Argentine capital, Brandini, then still at the Federal University of Paraná, invited oceanographer Demetrio Boltovskoy, from the Federal University of Buenos Aires (UBA), who embarked with students from his group. “We did great studies about plankton [microscopic aquatic organisms generally carried by marine currents], cited regularly until today by other researchers,” says Brandini. PROASA also seeks to promote this type of interaction.

Brazilian NavyThe Brazilian research base in Antarctica in 2021Brazilian Navy

Oceanographer Alberto Piola, also from UBA, who collaborated on one of the articles, has maintained an intense collaboration for at least 25 years with the group of Edmo Campos, of the IO-USP. “In the first 10 years, the research dealt with the effect of the La Plata River on the continental shelf of Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil. Since 2009, our collaboration has covered the meridional circulation of the South Atlantic Ocean by means of the SAMOC [South Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation] project and the change in water temperature at the bottom of Antarctica.”

The subject of the first expedition of the Alpha-Crucis oceanographic research ship, in 2013 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 203), SAMOC created “a culture that is generally seen as inclusive for women,” according to researchers from the USA, Germany, and South Africa who examined the history of the project in an article published in January in Communications Earth & Environment.

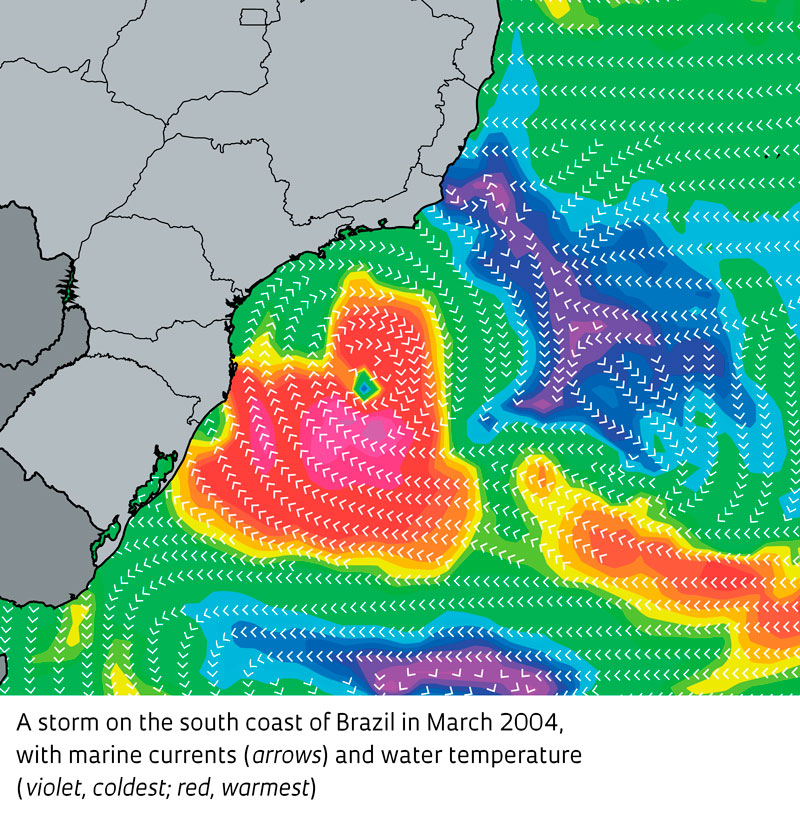

New possibilities for international cooperation have been discussed recently. In the annual meeting of the UN General Assembly, held in September 2023 in New York, representatives from 32 countries signed the Declaration on Atlantic Cooperation, to jointly promote economic development and environmental protection. In an interview with the Associated Press, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken highlighted that the Atlantic hosts the largest quantity of international maritime transport and, through submarine cables, is an important route for data traffic, but is threatened by climate change, which has brought stronger and more devastating storms, such as those in the south of Brazil in early September. “The Atlantic connects and sustains us like never before,” says Blinken.

Since 1986, the National Science Foundation (NSF), one of the main science funding agencies in the USA, has supported studies on the South Atlantic by researchers from Universities in the USA on themes such as magnetic field variations, acidification, marine currents, biodiversity, and carbon dioxide absorption.

In turn, the UK invests in research about the South Atlantic through the nongovernmental organization (NGO) South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI). Created in 2012, SAERI receives graduate students and scientists from the USA and European countries, who have published an average of 13 articles per year in the last five years on biodiversity and aquatic and marine environments.

SAERI is part of a growing international network of NGOs that seek to work with government agencies and universities. To discover the reach of the scientific collaboration in the region, a group from the State University of Santa Cruz, in Bahia, identified 526 institutions (NGOs, research institutes, universities, and government agencies) that work in the so-called Southern Cone, made up of Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and four states of Brazil (the three from the southern region and São Paulo).

One of the groups, selected for more in-depth analyses, included 23 organizations that are part of the Forum for the Conservation of the Patagonian Sea, created between 2004 and 2020, of which 12 are from Argentina, 4 from the USA, 2 from Chile, 2 from Brazil, 2 from Uruguay, and 1 from the UK. As described in an article published in the October edition of the journal Environmental Science & Policy, the 23 organizations mobilized 529 researchers or institutions, producing 272 scientific articles in English, Portuguese, or Spanish from 2004 to 2021, with an average of six institutions per publication. “Each country has to remember that it depends on the others to advance,” Janina Onuki reiterates. Piola, from Buenos Aires, values the institutional initiatives and stresses the importance of personal relationships, “very important for creating trust between the research groups and strengthening collaborations.”

Scientific articles

EDWARDS, M. When defence drives foreign policy: Brazilian military agency in the revitalisation of the Zopacas. Conflict, Security & Development. Vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 179–97. May 2023.

GRENO, F. E. et al. NGO scientific collaboration networks for marine conservation in the southern cone: A case study. Environmental Science and Policy. Vol. 148, 103554. Oct. 2023.

PEREZ, R. et al. Inclusive science in the South Atlantic. Communications Earth & Environment. Vol. 4, 11. Jan. 19, 2023.