“The Caatinga is actually many Caatingas,” summarizes botanist Daniela Zappi, one of the authors of the paper. Zappi has been visiting the rural Northeast since 1987, mainly in search of cacti, which she studied for her master’s degree, PhD, and much of her 23-year career at Kew Gardens, UK, before she returned to Brazil to work at two research institutions in Belém and Brasília.

“The Caatinga is home to jaguars, cougars, and tapirs, amidst landscapes of stunning beauty,” adds biologist Marcelo Moro, leader of the study, who has been doing research in the region since his days as a biological science student at the Federal University of Ceará (UFC). He began documenting the geographic distribution of plant and animal species in the biome during his PhD and postdoctorate at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), with funding from FAPESP.

Eric Hunt / Wikimedia Mimosa borboremae, found only in the forests of the Borborema plateauEric Hunt / Wikimedia

In August 2016, he returned to UFC to work as a professor. “I realized that to map the entire region, we would need more people,” he said. He was joined by two geographers who specialize in mapping species: Rubson Maia from UFC and Luis Costa from the State University of Montes Claros (UNIMONTES), in Minas Gerais. He also managed to bring on board four botanists: Zappi, retired botanist Nigel Taylor of Kew Botanical Gardens, Vivian Amorim of the Federal University of Cariri, and Luciano Queiroz, from the State University of Feira de Santana in Bahia. Zappi and Taylor are experts in cacti, Amorim in asteraceae, a large botanical family with 32,000 species, and Queiroz in legumes, a family of 19,000 species.

The group of botanists was tasked with delimiting the areas occupied by 328 plant species exclusive to the Caatinga. The cacti Cereus jamacaru and Xiquexique gounellei grow throughout the region but not in neighboring environments, while Tacinga mirim, another cactus, was only found in Ceará. Borreria apodiensis, an herb with small white flowers, is found only in Chapada do Apodi, on the border between the states of Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará, where there are many caves. A 20-centimeter spiny rat called Proechimys yonenagae and at least 30 lizard species are exclusive to the dunes of the São Francisco River in northeastern Bahia (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 57).

Rafael M. R. Serra Rodrigues’s four-fingered teiid (Procellosaurinus tetradactylus), found in the São Francisco dunesRafael M. R. Serra

The work by Moro and his team is based on a previous classification that describes eight ecoregions, formulated by zoologist Agnes Velloso of the nongovernmental organization The Nature Conservancy Brasil (TNC Brasil), forestry engineer Frans Pareyn, and agronomist Everardo Sampaio, both from the Northeast Plants Association (APNE), and published as a book by APNE in 2002.

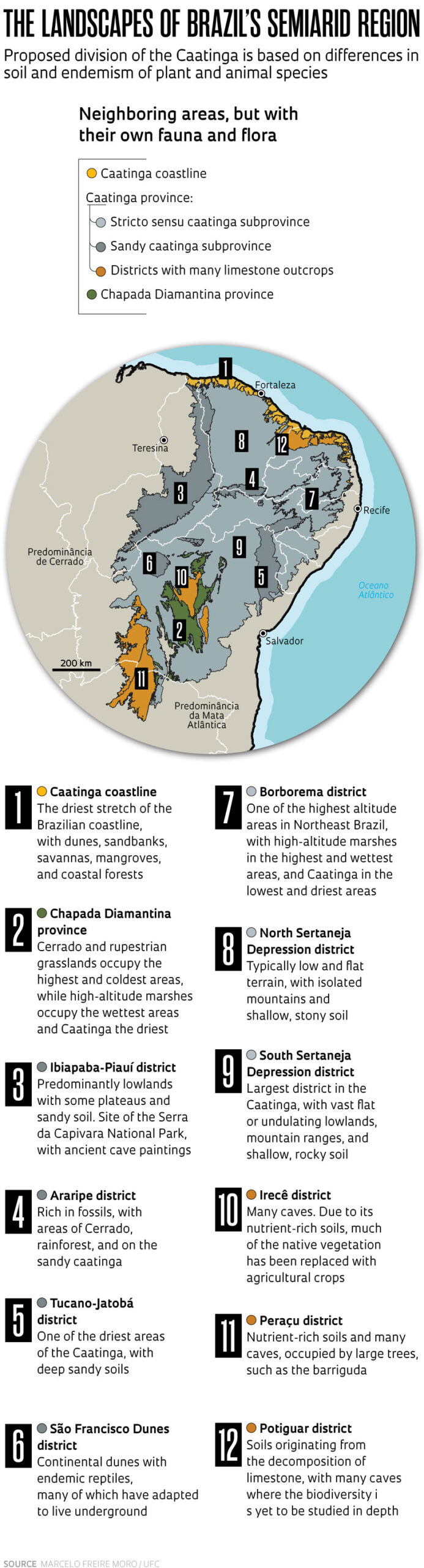

The new division of the Caatinga used international nomenclature for delimiting areas of endemism (from largest to smallest: kingdom, region, domain, province, and district), made official in July 2008 by the Journal of Biogeography (see detailed definitions in the online version of this report). According to this classification, the entire Caatinga is considered a biogeographic domain. The three largest units are provinces and subprovinces: the Chapada Diamantina mountains and two caatinga subtypes (written here in lowercase because they are a part of the Caatinga): stricto sensu and sandy.

Rubson Maia Trees grow in a hole in the sedimentary terrain of Irecê, BahiaRubson Maia

Stricto sensu caatinga, meaning “in a strict sense” in Latin, is located on land comprised of crystalline (volcanic) rocks and stony and moderately fertile soil. It has three subdivisions (biogeographical districts) of its own—the North and South Sertaneja Depressions, and the Borborema District—each with its own communities of animals and plants, despite the fact that they are neighbors. The palm tree Syagrus cearenses and the lizard Tropidurus jaguaribanus, for example, can only be found in the North Sertaneja Depression; the shrub Holoregmia viscida and the legume Tabaroa caatingicola only grow in the South Sertaneja Depression; and the cacti Pilosocereus chrysostele and the lilac-flowered herb Mimosa borboremae only live in the Borborema District.

The second major unit of the Caatinga, the sandy caatinga, comprises a terrain of sedimentary rocks that give rise to nutrient-poor sandy soils. It is further divided into four sub-units, each with its own species. The Cearanthes fuscoviolacea flowering plant is endemic to the Ibiapaba-Piauí district; the Araripe manakin (Antilophia bokermanni), a small and colorful bird, lives only in the rainforests of Araripe; and the Scriptosaura catimbau lizard is typical of the Tucano-Jatobá district and generally lives underground. The rodent Trinomys yonenagae, the lizards Procellosaurinus tetradactylus and Eurolophosaurus divaricatu, and the snakes Typhlops yonenagae and T. amoipira live only in the sands of the São Francisco dunes.

Nina Wenóli /iNaturalist Lear’s macaw (Anodorhynchus leari), typical of the Brazilian semiarid Caatinga biomeNina Wenóli /iNaturalist

In both the stricto sensu and sandy caatingas, plants have adapted to the dry climate: many species lose their leaves at the beginning of the long dry season and quickly regrow them as soon as the first rains fall. They are also both home to species found in the Atlantic Forest, the Cerrado, and dry areas of the Pantanal, such as the trees Anadenanthera colubrina, Piptadenia retusa, and Astronium urundeuva. “There are also small enclaves of dry forest in the Cerrado and the Atlantic Forest,” says Moro. According to him, dry forests in Bolivia, Venezuela, and Colombia also have species in common with the Caatinga in Brazil.

The province of Chapada Diamantina, part of the domain of the Caatinga, comprises high-altitude areas of Bahia, with Caatinga vegetation, tropical forests, savannas, and rupestrian grasslands (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 86).

Marcelo Moro Preserved forest in Itapajé, CearáMarcelo Moro

Another group of units comprising three more districts—Potiguar, Irecê, and Peraçu—where there are many limestone outcrops (exposed rocks), cave networks, and animals about which little is known, were not distinguishable from one another on previous maps. Some of these caves are within the Cavernas do Peruaçu National Park.

A final unit is found isolated in the north, near the coast. Dubbed the Caatinga Coastline, it is home to plant species typical to the biome, as well as to the Cerrado and the Amazon, due to higher levels of rainfall on the coast than further inland.

Moro and his team are mapping the enclaves of rainforest in highlands in the middle of the Caatinga, known as high-altitude swamps, where there are plant and animal species also found in the Amazon and the Atlantic Forest, as well as others that are endemic. Their plan is to finish the mapping process next year.

“Without knowing the conditions under which a species occurs in a given location, it is not possible to recover a degraded area, because the first question is ‘which species do we need to plant?’” explains UNICAMP biologist Fernando Martins, who did not participate in the research but has been studying the Caatinga for 30 years and was Moro’s doctoral and postdoctoral advisor.

Domingos Cardoso Cacti and other plants in Irecê, BahiaDomingos Cardoso

“Furthermore,” he continues, “there are species able to live together and others that cannot due to competition. Species living in similar habitats can live together, since competitive exclusion has already occurred. By associating species with regions of similar environments, a lot of essential information is obtained both in the theory of biology and in practice.”

Martins was pleased to see that the shapefiles (layers) of the map, each identifying the different types of environment within the Caatinga, were published digitally via open access, allowing any researcher to associate the data they collect with distinct areas. “This is very important to improve our understanding not only of how it was possible for such a diverse and regionalized biota to evolve in such a harsh environment, but also of how to conserve this biodiversity and establish new conservation units capable of protecting the biota from climate change,” he says.

Marcelo Moro Coastal field with carnauba palms (Copernicia prunifera) in Jericoacoara National Park, CearáMarcelo Moro

Biologist Marcela Cruz Moreira, advised by Martins during her master’s degree, compared species of angiosperms (flowering plants) from crystalline and sedimentary terrain in the Caatinga. The initial hypothesis was that sedimentary terrains, where the soil is deeper and better able to retain water, would be home to very different species. But that was not the case. “Crystalline terrains, which we thought would be more selective, support a wider range of species than sedimentary ones, which might suggest the existence of highly complex evolutionary processes,” says Martins.

Marcelo Tabarelli, an ecologist from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), says: “The new study offers a more accurate view of the Caatinga, until now considered a single entity, although we who visit it know that it is not. This type of division, based on the physical characteristics of the environment, should work well for plants, but I don’t know if it will also apply to other taxonomic groups.”

Luis CostaPeruaçu Caves in the north of Minas GeraisLuis Costa

Brazilian geographer José Maria Cardoso da Silva, from the University of Miami, points out: “The big question today is how much of the Caatinga’s patterns of endemism are the result of human pressure in the region.” Abandoned or current agricultural and pasture areas cover 89% of the biome—a stark contrast to what it must have been like thousands of years ago, with the same climate and soil conditions but before human occupation, according to studies led by biologist Helder Araujo of the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), published in Scientific Reports in October 2023 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 335).

“Deforestation has been widespread since the sixteenth century, especially in the east, in the North and South Depressions, and in the Borborema District,” says Araujo. “A lot of riparian forest has also been lost, and it is now rare alongside rivers like the São Francisco.” The main conservation units in the region are located in the sandy caatinga, such as the Serra da Capivara National Park, the Raso da Catarina Ecological Station, and the Araripe-Apodi National Forest, which offer examples of some of the original environments of the Caatinga.

The story above was published with the title “The surprising faces of the Caatinga” in issue 344 of October/2024.

Projects

1. Analysis of the phylogenetic structure of plant communities in the Caatinga phytogeographic domain (n° 13/15280-9); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Fernando Roberto Martins (UNICAMP); Beneficiary Marcelo Freire Moro; Investment R$241,517.63.

2. Phytogeographic meta-analysis of the Caatinga biome (nº 09/14266-7); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Fernando Roberto Martins (UNICAMP); Beneficiary Marcelo Freire Moro; Investment R$159,684.61.

Scientific articles

EBACH, M. C. et al. International code of area nomenclature. Journal of Biogeography. Vol. 35, no. 7. pp. 1153–7. July 14, 2008.

MORO, M. F. et al. Biogeographical districts of the Caatinga dominion: A proposal based on geomorphology and endemism. The Botanical Review. In press.

Book

VELLOSO, A. L. et al. Ecorregiões propostas para o bioma Caatinga. Associação Plantas do Nordeste. The Nature Conservancy do Brasil. 2002.

Republish