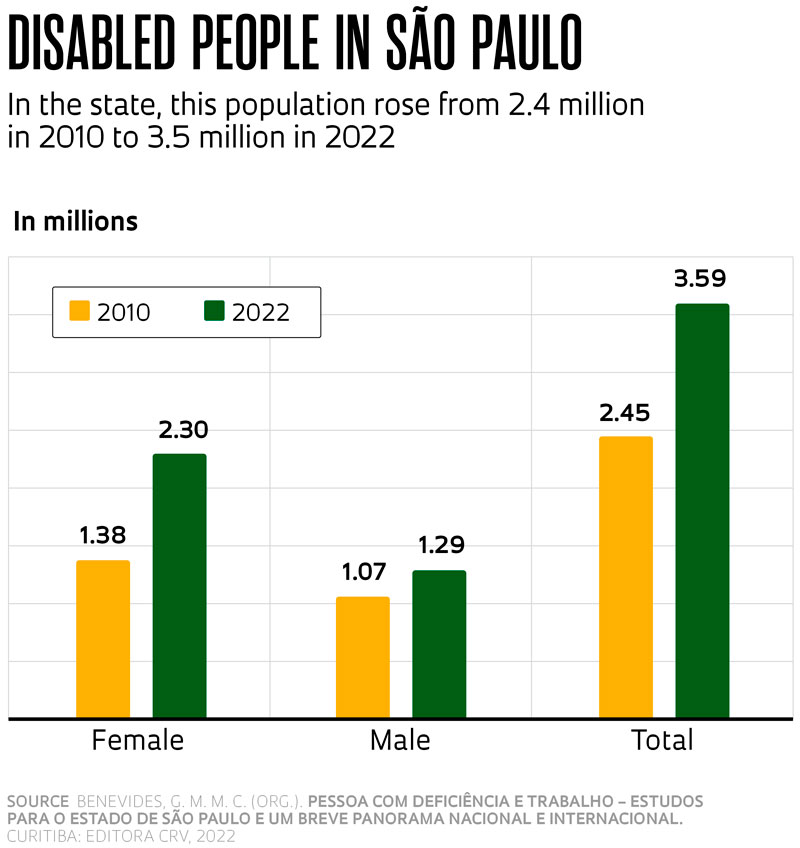

Between 2010 and 2020, the number of disabled people with formal employment bonds in the state of São Paulo increased from 96,200 to 148,00 — a 54.6% rise. Despite these advances, 83.7% of companies in the state do not comply with Law no. 8.213/91, which provides that companies with 100 or more employees must reserve some of their vacancies for that section of society. The findings are part of a study by researchers from the Institute of Economy at the University of Campinas (IE-UNICAMP), conducted since 2021 with funding from the Labor Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPT). Access to the workplace is one of multiple issues for disabled people being studied across different areas of knowledge.

In 2021, the state had on record 11,800 companies obliged to reserve vacancies for this group of people. Of all these companies, only 1,800 complied with the quotas stipulated by the law—15.9% of the total. “The percentage recorded in São Paulo is lower than the average for Brazil, where 23.6% of corporations meet the legislation requirements,” compares economist Guirlanda Maria Maia de Castro Benevides, of IE-UNICAMP and one of the study authors. The researcher points out that since 2010, the number of disabled people employed has reached an average growth rate of 5.1% per year. In her opinion this movement results primarily from the existence of legislation ensuring formal employment for this group. “However, we still have a ways to go in terms of complying with the Law of Quotas,” she emphasizes.

Pursuant to Article 93 of the law, the percentage of vacancy reservations varies in accordance with the size of the corporation. Companies with 100 to 200 employees are obligated to include a total of 2% employees with disabilities in their staff, while for organizations with 201 to 500 workers, this percentage rises to 3%. Establishments with 501 to 1,000 professionals must fulfil the minimum level of 4%, and for those with over 1,000, the number increases to 5%.

Between 2003 and 2015, Benevides coordinated the Program for Employment Inclusion in Campinas, run by the Brazilian Ministry of Labor and Employment (MTE). “One of the claims we were hearing frequently from organizations that were defaulting on this legislation is that the quotas were not being completely filled because there were insufficient disabled professionals available in the market,” reports the researcher. With an end to exploring this question, the UNICAMP study demonstrated that in 2021 São Paulo had some 1.8 million people with disabilities in the 16 – 64 age group potentially fit for the employment market. Considering all the companies in the state, the number of vacancies for people with disabilities totaled 327,500, with less than half (45.4%) filled that year — 148,800 job posts. “Generally speaking, the companies were hiring but did not achieve the minimum percentage set by the law,” explains Benevides.

Average annual growth rate of disabled people employed is the result of legislation ensuring formal employment

The UNICAMP study also found that vacancies filled in São Paulo in 2022 were chiefly in the services sector, followed by industry and trade. Most of the employees had completed high school (52.5%) or higher education (19.9%). People with physical disabilities registered 75,800 formal employment bonds in 2022, or 45.6% of the total, while the equivalent value for those with hearing impairment was 19%. Participation was lower among people with mental and intellectual challenges — 14.2%, or 23,500 employment bonds.

Between 2010 and 2020, formal employment bonds increased across all age groups except for 16–24, which saw a drop of 12% (see graph). “The downturn in the economic growth rate in Brazil and the health crisis caused by COVID-19 impacted the employment market as a whole, more significantly affecting young people, particularly those with disabilities,” says economist Jacqueline Aslan Souen, of IE-UNICAMP, who also took part in the research. According to the survey, white disabled workers filled 59.6% of formal vacancies. Brown-skinned people came second (26.2%), followed by Black workers (6.9%). The study was conducted based on the cross-referencing of data available in the Labor and Employment Ministry’s Annual Social Information Report (RAIS-MTE) and in home surveys conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).